Episode #59: Radio Show: The Death of Value Investing

Guest: Episode #59 has no guest, but is co-hosted by Jeff Remsburg.

Date Recorded: 6/22/17 | Run-Time: 1:07:08

Summary: Episode 59 is a “radio show” format. This week we’re diving into some of the recent market stories which Meb has found most interesting. We also bring back some listener Q&A.

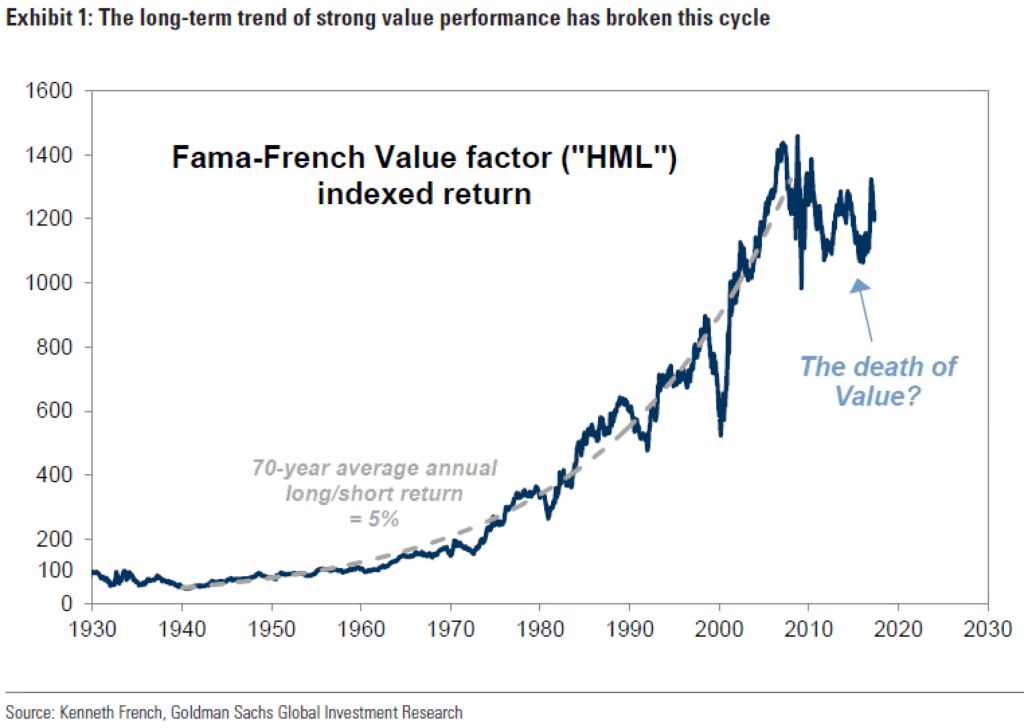

We start with a Tweet from Cliff Asness, in which he rebuffs a Bloomberg article titled, “The Death of Value Investing.” The article states that value “isn’t working. Sticking to that approach has resulted in a cumulative loss of 15 percent over the past decade, according to a Goldman Sachs Group Inc. report. During roughly the same period, the S&P 500 Index has almost doubled.”

So is value investing dead? Meb gives us his thoughts. We discuss its underperformance, mean reversion, and factor-crowding.

Next up is a New York Times article referencing a recent stance-reversal from Burt Malkiel, a passive investing legend. He’s now saying he recognizes where active investing can exploit certain market inefficiencies. The same article has some great quotes from Rob Arnott on the topic of factor investing – and the danger in tons of quants all looking at the same data and trading on it. Meb gives us his thoughts on factor timing and rotation, using trend with factors, and the behavioral challenges involved in both.

Another Arnott quote steers the conversation toward backtesting – the pitfalls to avoid when backtesting, so you don’t create a strategy that looks brilliant in hindsight, but is hideous going forward.

Next up are some listener questions:

- I still can’t wrap my head around how to use commodities in a portfolio. The Ivy Portfolio promotes putting 20% in a broad commodity index, but in the podcast, I’ve heard you discuss the financialization of commodities futures leading to loss of roll yield. So what’s the answer here? Include commodities as an inflation hedge but be prepared to pay the price of long term drag? Or forget about commodities and just focus on stocks/bonds/real estate?

- Please explain the difference between the unadvised practice of performance chasing and the highly encouraged practice of momentum investing.

- I would like to know your thoughts on implementing lifecycle glidepaths for an individual or clients’ portfolio. Your quant-style approach looks at risk a lot different than most, but I do see value in reducing portfolio risk as you come closer to withdrawing the money – the question is which risk, or what approach do you use to reduce the risk? Regarding your trinity style approach, does that mean reducing from a Trinity 5 to a Trinity 3 (for example) a couple years prior to retirement?

There’s plenty more – including our new partnership with Riskalyze, which enables advisors to allocate client assets into Trinity portfolios. But the more interesting story is how Meb gave his wife food-poisoning the other night. How’d he do it?

Sponsors:

- FoundersCard – The exclusive community for entrepreneurs, innovators, and business professionals offering networking as well as exclusive offerings to the best brands in travel, lifestyle and business.

- The Idea Farm –The Idea Farm gives small investors the same market research usually reserved for only the world’s largest institutions, funds, and money managers.

- Freshbooks – Small business accounting software that makes billing painless

Comments or suggestions? Email us Feedback@TheMebFaberShow.com or call us to leave a voicemail at 323 834 9159

Interested in sponsoring an episode? Email Jeff at jr@cambriainvestments.com

Links from the Episode:

- Meb’s blog

- Meb’s Twitter

- Meb’s Tweets of the week

- Cliff Asness’s tweet on The Death of Value Investing

- “Goldman Sachs Mulls the Death of Value Investing” – Bloomberg Markets

- Burt Malkiel article re: passive/active investing (also lots of Arnott quotes) – New York Times

- Invest Like The Best Episode 41

- Vanguard is at $65B in assets – Investment News

- Cambria’s new Trinity for Advisors offering with Riskalyze

Transcript of Episode 59:

Welcome Message: Welcome to The Meb Faber Show where the focus is on helping you grow and preserve your wealth. Join us as we discuss the craft of investing and uncover new and profitable ideas all the help you grow wealthier and wiser. Better investing starts here

Disclaimer: Meb Faber is the Co-founder and Chief Investment Officer at Cambria Investment Management. Due to industry regulations, he will not discuss any of Cambria’s funds on this podcast. All opinions expressed by podcast participants are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of Cambria Investment Management or its affiliates. For more information visit cambriainvestments.com

Sponsor: Today’s podcast is sponsored by FoundersCard. I usually don’t spring for a paid membership programs but this one is a little different. The offering has targeted entrepreneurs and business owners. And the card enables premier benefits from leading airlines, hotels, life-style brands and business services.

A few of my favorite benefits include free access to MailChimp Pro, Dashlane Premium, and TripIt Pro. You can even get big discounts at services I love, like Silvercar, 99designs, Apple, and AT&T.

My favorite though, are the travel benefits where you get an automatic status such as Hilton Honors Gold, American Airlines Platinum and Virgin America Gold. And while I often use the great app HotelTonight for travel, the FoundersCard discounts can be massive too.

If you go to founderscard.com/meb podcast listeners can sign up for the discounted $395 a year with no initiation fee. And that’s a saving from the normal cost of around $600 per year, again that’s founderscard.com/meb.

Meb: Welcome to a summer-time podcast, sitting here with co-host and podcast show producer Jeff. Welcome, Jeff.

Jeff: Hey what’s happening?

Meb: Not much. Winding down getting ready to have my birthday here in about a week.

Jeff: ‘grats.

Meb: Thank you very little.

Jeff: What are we doing for it?

Meb: Is that Chevy Chase line? What is that from?

Jeff: “Fletch.”

Meb: “Fletch?” Let’s see if we can pull up the video for that. I don’t know what I’m gonna do for it. Hide in a dark closet. Avoid…

Jeff: [inaudible 00:02:24]

Meb: No, I love birthdays. Listeners, if you want to send me a birthday present, feel free.

Jeff: Are you willing to reveal what you’re turning?

Meb: We’ve gotten quite a few weird presents so far from listeners.

Jeff: Deflection.

Meb: We’ve gotten smoked salmon, iced wine, Jeff got a bottle of Tequila which he promptly took home, didn’t share with anyone.

Jeff: We haven’t received enough.

Meb: Margarita Friday we need. Yeah. So we’re wedging this. We’re doing a Q&A radio show in between, we had a fun on with Axel Merk. And then we have a really exciting one coming up with Doctor William Bernstein. If you have questions please send them in. He’s one of the oft-requested podcast-show guests and it’s going to be a lot of fun. So if you have any…We’re looking forward to it. It’ll be out next week.

Jeff: Cool. Well why don’t we dive in with some tweets that you made over the last week and then some reader Q & A?

Meb: You saying that makes my stomach turn a little bit, saying like, “Let’s dive into some of your tweets.” Because I feel like sometimes, it’s hard for me not to behave poorly on Twitter. But go ahead, fire away.

Jeff: All right. First one is a tweet that actually it referenced Cliff Asness, where he was rebuffing a Bloomberg article called. “The Death of Value Investing.” So the article claims that value isn’t working. Says, sticking to that approach has resulted in a cumulative loss, 15% over the past decade according to Goldman Sachs. During roughly the same period, the SMP 500 was nearly double. So first, why has it underperformed so much?

Meb: I imagine that stat is not straight-up value, his loss is probably long-short or value versus growth depending on where you pulled that quote. So it’s definitely underperformed, the market cap. Almost everything is underperformed market cap weighted in this cycle, which is normal and it’s fine. I mean it’s so much of what goes on in investing is the ebb and flow, the waxing and waning of styles, and countries, and sector, and strategies. And that’s just kind of the way that it is. You know, things go in and out of fashion.

You have times when market cap is crushing everything else, and the U.S. is crushing other countries. You have times when Greece is outperforming, like this year. So a lot of these things are, you know, you see it on managed futures. Every five years, managed futures is dead, trend [SP] volume is dead. And then, fast forward another five years after everyone’s rushed in and it’s been an unbelivable performer. It’s, same story.

Jeff: Well, one of the things the article is trying to claim, it’s got a chart which will post and it draws a smooth line over the course of, I guess, it’s since 1930. And the line basically follows a consistent progression, and apparently we’ve truly broken this since around, looks like, around 2010 or so.

So I mean do you see this as potential…Based upon what you just said, is this where meaner reversion’s gonna mean that we’re way undervalued right now, in terms of value as a factor and has come roaring back. Or do you think something can potentially actually change from a structural perspective, and it is broken, in a sense.

Meb: Well, who knows? I mean, look, you have like, late ’90s for example, and that’s a classic example of, you know, things continuing longer than people expect. And, in many cases, and I don’t think we’re in a bubble. But when bubbles get into late stages is when a lot of people can make a lot of money, you know.

And so it could continue on for a couple of years, but that’s the way that works. I mean our friend Wes talked about it as a value pain train. And we often cite the example, you know, Warren Buffett’s 13F holdings underperforming 8 of the last 10 years. But these things happen and that’s just, kind of, the way it goes, and it’s not just value, it’s tactical. You know everything you hear in the news today about active versus passive. And all the flow’s going into passive and passive crush…

These things have a way of coming in and out of favor. I mean in general you still want to make smart bets, and investment approaches that are kinda tried and true, as opposed to just flipping around to whatever happens to be working today.

Jeff: We’ve talked about flows. Is this just an example of, well, the source of value being underperformed or…let me back up. If it actually was doing well. I would assume that’s because flows were chasing performance, it was doing well. Is this then what we’re seeing? Basically investors chasing the hottest factor, and then sort of behaviorally, you know, they bail at the wrong time, they buy in at the wrong time. And basically, it’s gonna come back now because everybody’s out of it?

Meb: You know, I mean yeah. I mean you kinda described the whole meaner version concept, right? Is that, but you never know. You don’t know if that’s 1 month, if it’s 5, 10 years. And so there’s…what you want to take…remember you got to take a long-term view and always ask yourself, has something changed, and is there a reason to why we should be thinking about it differently?

You know, we talk a lot about dividends yields and dividends stocks and shareholder yield and that’s a case where things have changed. But in general, value as a concept? No, of course not. Now every bull and bear market has different personalities and it’s same old stuff.

Jeff: Okay, well, keeping on the topic of factors then, you just tweeted about a New York Times article in which Burt Malkiel reversed his stance on passive versus active investing. Now generally believing that active investing can exploit certain market inefficiencies.

Now, it’s kind of ironic that this comes when he’s backing Wealthfront’s new advanced indexing service which is performance mark [SP] data. So it’s not really my main question, but first I’m curious whether you see this purely as a marketing move or…?

Jeff: Look, I think Burt Malkiel is a national treasure. I mean, I think he’s one of the legends of investing. His books, I think, are excellent. I think you always need to separate people from, kinda, what they’re saying and what they do.

Burton’s been on the board and chairman and investment advisors, he’s like, it’s like 20 or some companies. I mean I remember once, like, an active emerging market fund that charges 2% a year. Right? So, it’s kind of what you say and what you promote necessarily, like, what you do. So I’ve always just kind of smiled when I hear Burton in the press, talking about these things. And Wealthfront being one where he’s been the, kind of, the CIO of it and they’ve, kinda, been famous critics of smartpay [SP], But, look, I applaud them from saying, “Hey, we think there’s there’s potentially a better way than marketing cap weighted indexing, you know.

And so I think it’s a smart move what they’re doing and I don’t have any problem with it. But, you know, its kind of funny. When you see people, Silicon Valley loves to pivot. And it’s a good thing, in general. You’re doing something wrong, you pivot. Great, you change. I think that’s a wonderful thing. Say look, you know when you’re doing something wrong, you improve. That’s the foundation for becoming a better person, becoming a better investor. Right? Is you change.

But it’s kind of funny that, depending on how you project yourself, prior. So if you’re philosophically very opposed to something and then change your mind. Like, Silicon Valley calls it pivot. Probably the rest of the country calls it just being full of shit. You know, depending on how you go about it.

So, if you’re like picking fights with people and saying how this is a terrible way to invest and then you kind of pivot to it. Like, is it because you’re trying to find a better market fit and something to distinguish yourself from the competition or do you really believe it?

And so a lot of these cases…Look, I think it’s a good improvement. I think it’s a smart thing to do. I think that the evidence says that you should probably move away from market cap weighting. I have no problem with that.

But, it’s kind of like a, you know, we’re from the South. Southern preacher being like, “You should never drink. You people are going to Hell. You should…” Then says, “Oh you know what a glass or two of wine every weekend’s fine.” And it just kind of has a weird feeling to it.

I just kind of laugh. It’s a humorous article but I actually think it’s a step in the right direction, I think they’re making a smart move. I mean they are still using high-dividend yield as a factor which we’ve talked about in the past. An article we did which is, you should basically never own high dividends yeilding stocks in a taxable account. We can talk about that later.

But still the quibbles I have. But, the whole thing about these robos, the top four…By the way they just announced that Vanguard is now up to $65 billion in assets. So that’s bigger than the next three combined, and they’re a bit of a cyborg. So they come with a financial adviser. Schwab second with like $20 billion-some and then betterment [SP] Wealthfront. They’re all good choices. I think they’re totally reasonable choices.

Now my philosophical leanings, and obviously I’m biased because we run a digital advisor is that something like the way we do it or Wes at Alpha Architect, the way they do it, which is a little more tactical with some trend following [SP] inputs, I think, is a better solution. But I think all four of those are just fine. I think they’re all good solutions.

Jeff: Makes me think of your idea that somebody tracks the various robos.

Meb: Yeah, if it’s a good website, someone listening should do it. You should come up with 10 default portfolios, for each of the robos because, none of them report performance, for some unknown reason. Set up a robo-tracker website and every journalist on the planet will subscribe to your website. I don’t think it’ll make any money but…

Jeff: So the curious thing to me about that article by Malkiel was actually a couple of quotes from Rob Arnott. One, he said that, pretty much everyone is looking at the same factors. Which is a danger. He added it’s a very crowded space, if 10,000 quants are all looking at the same data and trading on it, the chances are it’s not gonna work.

So, I mean it kind of makes me wonder investing now is different than, call it, 30 years ago because it seems like there is a lot more market scrutiny of all sorts of factors and what not. And the one that sort of persists, the time, is really the behavioral element. How do you not react? What do you think is the best way to capture the behavioral side? Is it trend following? Is it…?

Meb: Oh, so Rob he’s been talking a lot. They’ve been doing a lot of research at Research Affiliates about factor timing. So that’s been a very big topic of discussion over the past year or two, with a lot of people falling [SP] on different sides of it. Can you time factors and meanings, say a factor, like for example, price to book or dividend yield. That historically, let’s say it adds 1% to 2% performance over market cap weighting.

But there’s times when because of money rushing in, and divident yield is a good example. So 1999 dividend yield, high-dividend yielding stocks traded at a 50% valuation discount the overall market, and on average is 20% over time. Now it’s a premium over the past few years for the first time ever.

So a common-sense person will say, “Whoa, okay. It makes a lot more sense to allocate a high dividend yield whereas [SP] in 1999 when there a huge valuation discount and it makes no sense now.” And so theoretically I really want to believe that factor timing is possible from a common-sense standpoint and Research Affiliates has shown research that shows if you sort factors based on, I think it’s their last three or five or something, year performance, excuse me, in valuations, that there is added a performance by tilting away from, you know, the high valuation and the ones that have done the best.

So, they have a beautiful new website by the way. If you go to Research Affiliates ask the allocation module that lets you look at a lot of these factors, and compare the current basket to history. And is that current basket expensive or cheap? So you have a factor like momentum. You say, “Oh wow, it’s falling in the top decile of most expensive, or under, you know, really cheap right now.” So maybe it makes more sense to be owning that.

Jeff: And is that valuation component, is that relative to itself? Or is there more of an absolute….?

Meb: Yes. That’s a good question, I’m trying to remember. I think it’s…I can’t, I’m blanking. I can’t remember if it’s relative to its own history, or relative to the current market. I don’t know. Go check it out.

Jeff: Okay. But tying back to the…that was in answer…

Meb: I forgot what the question was….

Jeff: That was an answer based on factors. You know, what I was wondering is, what do you think of, when you’re trying to exploit the behavioral biases we have, is it trend following to sort of go with what the direction is, what the behavior, what the sentiment is, regardless of factors such as, you name it and to, sort of, go with the bias, or…?

Meb: There’s a couple of different approaches as far as implementation. So first is, look I’m gonna put together a portfolio of these factors, and that’s that. They’ll balance out over time. So I’m gonna own some value, I’m gonna own some momentum. Rebalance once a year, whatever. Okay? That’s one. Two, is that trend following certainly works and it’s a different approach. Right? And…

Jeff: You don’t consider that a factor, do you?

Meb: Right, but no. Trend following, no. It’s…

Jeff: Like an overlay.

Meb: No it’s an active management overlay on anything. So you can overlay trend following on corn prices, or gold, or the Swiss franc, or bitcoin right? You can overlay trend following on dividends stock. So you’re applying an active management approach to a factor-based approach. And I think it works great over time, philosophically speaking, lines up.

But if you’re looking at a lot of these factors you know we’re talking a little more about mean reversion where, if a factor has done really well over the past XYZ years, that maybe it’s time to be moving away. So rebalancing is certainly one solution, as is potentially, what Rob had talked about in our podcast, which is over-rebalancing. Meaning if, and here’s a good example.

So if you’re doing factors with a global valuation of countries or something, where you say all right, well this cheap basket of countries is in the cheapest that it’s ever been. Maybe it makes sense instead of just rebalancing, rebalancing a little more. So if that’s 10% of my portfolio instead of rebalancing back from 8 to 10 we actually rebalance up to 12 or 15 or something.

So it’s just kind of turning the dial a little bit more, but again, you know, all of this stuff plays out and it’s simple to look at. Because I’ve been thinking for a long time what is gonna be the bubble, or the tell, of this market cycle. So, late ’90s internet stocks and a lot of other tech, right? Super expensive.

Not the case now. Tech stocks are totally reasonable compared to their history in the market. 2007 was a lot of leverage in credit as well as real estate.

This market cycle, I had often scratched my head. You see little mini bubbles like Toronto real estate where Pitbull and Tony Robbins are speaking in conference, pumping Toronto real estate. Right? But you’re starting to see a lot of bubble-like behavior with the cryptocurrencies. A lot of people who have no business, ever, getting involved in the stories. And like, the story of this man put in $1,000 and now he’s a millionaire.

Jeff: I think I saw Ethereum [SP] is up 4,000% this year.

Meb: And then there was some, like, flash crash where it went down to, like, 13 yesterday. Like, so, it’s drawing in people now. This does not mean…Again like if you could compare to something like NASDAQ, late ’90s. Is this ’96 with cryptocurrencies? Or is this 1999?

Jeff: Yeah, but to what extent? I mean this is a small pocket, you’re talking about cryptocurrencies and you were [crosstalk]…but I asked you a moment ago what’s gonna sort of burst this market, cryptocurrencies don’t have much control over the broader market.

Meb: No, no, no. They’re an afterthought, but I’m just saying you start to see bubble-like behavior in areas, and usually it involves leverage or credit, or just people being somewhat foolish.

A lot of the cryptocurrency stuff goes on outside the U.S., by the way, it’s not necessarily…On a day-to-day basis, I mean we go to lunch or dinner tonight I can’t pay with Bitcoin. San Fran you probably could, that’s about it. Anyway. So yeah, I mean, but the whole point is that, if you look at the history of onvesting is all of this stuff just ebbs and flows. And you see the same stuff over and over again and the media is particularly wonderful usually about usually getting it wrong on time frames where, when they’re calling for the death of a particular style it’s usually an interesting time to be interesting.

Jeff: Intentionally.

Meb: Yeah, and vise versa.

Jeff: Okay. Another quote from Arnott on that same article. He says, “Smart data can be smart and then it can be not so smart. There are tons of strategies being offered now based on nothing but back tests. Anyone can create a brilliant strategy with the benefit of hindsight. Does that mean anything for future returns?”

I’m curious to bring this up because a lot of what we do in houses, we look at things from a a back test perspective. So I’m curious as to your thoughts on how to distiguish between accurate and effective back tests, with integrity, versus those that are manicured or contrived or what not.

Meb: You know I think the biggest benefit of back testing is simply, it’s like reading about history. So understanding what markets have done in the past. And if you just relied on back tests and didn’t use any sort of common sense, one thing would be, all right well you should never invest in China, or Russia, or Agentina, or Egypt, or Japan because, at one point they’ve essentially lost the entire equity market. So you should never invest in that.

And like that would be a weird sort of takeaway. Right? But in general it’s just like have a respect for history and understand what’s possible and what can happen. You know, most young investors here to tell them you know United States government actually confiscated people’s gold and made people turn it in, a 100 years ago almost. Can you imagine the U.S. government doing that? They’d say, “No. You’re kidding me. Right. You know, that’s crazy.”

Or if you said the U.S. market has dropped by over 80% before and commodities and REITS in the last bear market dropped by over 70%. All these sort of take aways. It’s like it actually probably makes you a lot more, back test in general, and a healthy respect for history gives you probably a lot more conservatism, and a lot more respect for what can and does happen.

But if you flip that, and say the people that are back-testing equity strategies to 2000 that are saying, “Hey look, this trade on Thursday buy on Monday strategy, has worked and beaten the SB by 10 percentage points a year since 2000, like that doesn’t really check the box, to me. So to me it is learn as much as history, as possible, understand as much as possible, what has happened and why. And then just put on a little common sense.

Jeff: Okay, I hear you on that but I think it was [crosstalk]…

Meb: And here’s a good example. So let’s say you’re a trend follower, and you say, “You know what? I love the 200 moving day average, it’s a great strategy. And you look at it, just back to 1999. Well, trend following has worked incredible, since ’99 because it missed two huge bear markets, for the most part. Right?

But then you take it back to the ’80s and you understand, oh, okay. Well, actually, depending on the trend volume metric you used, it would have either sat in or out the 1987 crash. And that’s a pretty big binary event. You either woke up that day, or that month and were up or down 20%, you know, depending. But had you not back tested, you wouldn’t really have that sort of understanding.

And so there’s so much that, you know, going back to the originial comment about Cliff Asness at AQR says, you take a lot of these back tests and going forward, he’s like, I’d like to take the draw down and double it.

And we have the concept that your largest…and it’s factual…the largest draw down is always in the future. And this is why a lot of people are suprised about 2008. You know a lot of the endowment-style models, a lot of people had a buy and hold model, those [SP] globally diversified. And the largest draw down going into that, was probably 20%-ish, and it doubled.

And endowments, our portfolio probably had a draw down of 50%.You know, Harvard Endownment goes mark [SP] to market on a monthly basis, would have lost half. You know, you having a healthy respect for history, but also understand that things can go wrong, and do. And that there’s worse cases, and understanding why your back test may be overstated, or may not work as well in the future.

I mean look at price to book, as an example, as a factor. The most famous, probably, value factor that’s been around for decades and then it’s had countless funds and strategies that have been based on price to book. You know, DFA were original pioneer in that $400 billion. But because so much money has moved into it, it’s been one of the worst factors since then. So we’d like to apply a little common sense, and generally kind of understand…I mean, we had a guy email us the other day, and said, hey Meb I was curious, looking at the strategy that they just launched five months ago. I’m wondering why it’s underperforming.

I said, “Are you serious? Like, this could go years underperforming. But unless you…” There’s big education gap, I think, too, which is tough.

Jeff: But to what extent though I guess what’s the biggest mistake when back testing I think of it like a survivorship bias. But are there some other obvious, egregious mistakes that you can avoid.

Meb: There’s a lot of really bad one-on-one mistakes that I actually don’t, like, even count. So I don’t even count survivor bias because that’s so egregious that, and survivor bias, listeners, that’s like, for example, if you were looking at historical stock performance but excluding stocks that no longer esxist. That would give you a very inaccurate historical back test.

And it’s actually surprising how many of this research websites, that I’ve used in the past, do things like don’t include dividends. Or don’t include delisted companies. And so people used to send me back tests that talk about that, and I’d say, “Look, this, no offense, but this is worthless. You’re excluding…This is not even remotely close to reality.” And are saying look at mutual funds that only exist today.

Jeff: So if we have listeners who are looking for more of a pure data set where will they find it.

Meb: It depends on what they want to do. If they’re just looking at asset classes that’s pretty easy, we have some tabs on our website. If you search historically, like free data sources. So, French Pharma [SP] has stock data on a monthly level for asset classes and countries and styles going back to like the ’20s.

But if you’re looking at individual stock basis and wanting to do back test. I mean there’s number of websites that will let you sort and back test. I mean if you had access to a business school fact set, which will otherwise cost you, like, $50,000 or $100,000 or something. But there’s a lot of websites and we mention them on our blog many times in the past. If you search like tactical back tests or something.

There’s a lot of ones that will do it. There’s never been a greater time in history that has more access to the data than now. So that’s like a 101. I don’t even count that as a mistake because that’s just like a do not even get to Go, starting point, sort of mistake. But a typical mistake would be something like, you know, you’re looking at a 100 factors and then optimizing the best 10 over the last 10 years and expecting that to continue.

You know that that’s a short time frame, considering that there is styles that go in and out of favor for an entire decade, or more. You know, and again going back to that old comment about everyone having the same data set. I agree with that.

I was making this comment the mid-2000s interviewing a quant hedge fund [SP]. You go type up on Yahoo Finance which, rest in peace by the way. I don’t even know that they’re supporting any more. Type in a ticker symbol and see who owns it. It’s five of the most famous quant funds. It will be like D.E. Shaw, LSV, AQR, so you know, they all kind of arrive at the same conclusion.

But there is certainly if you’re a quant, and there’s great podcast that Patrick O’Shaughnessy did with the CEO and founder of Estimize a few weeks ago, that talks about this. And it says, you know, a lot of these quant shops, the new value add has become finding new factors, new data sets.

And finding ways that people either, you have data that no one else has, or you look at the data differently. But the flip side of that, if you’re an individual investor like, “My God, how am I going to compete with that?” There’s another quote from Josh Brown. He’s like, the Alpha is to do the opposite, and to be as dumb as possible, and to take a step back and operate in a totally different timeframe, where you’re not necessarily doing high frequency trading, or trading the ultimate quant stock factor model in the U.S. Maybe you’re applying it to Malaysian securities, or frontier markets, or private equity companies. You know, there’s a lot of different ways to skin a cat.

Jeff: I remember reading some quote that basically arrived at the conslusion that the greatest alpha that retail has is just time frame. As long term, you know, we’re not competing like asset managers short-term [inaudible 00:27:51] peformance to keep your job. So if you’re willing just to be patient and stick with your strategy and have a longer term perspective.

Meb: I love the coffee-can strategy portfolios, which is people that have bought stocks and then just put them away. And I actually think that’s a great way to buy a portfolio. We talked about this in a prior episode where I said you could buy an investment and never sell it. So it has to stay there no matter what.

So these people that end up owning GE for 40 years or Reynolds Tobacco or whatever it may have been, that have these just…You know you read the story about the janitor that just left $4 million dollars to a local autobahn society because he owned stocks that he just never sold.

Jeff: Yeah, there’s [SP] a million stories like that.

Meb: Yeah, and it’s great and I think that’s totally resonable way to invest.

[00:28:30]

[music]

[00:28:32]

Sponsor: And now a word from our sponsor. Today’s podcast is sponsored by FreshBooks the best cloud-based small-business accounting software. Look I’ve never taken an accounting class in my life and found FreshBooks easy to navigate within the first 30 seconds.

Here’s an example. Say you’re racing against the clock to wrap up three projects. Prepping for a meeting late in the afternoon, all while trying to tackle a mountain of paperwork. Welcome to life as a freelancer. Challenging? Yep, but our friends at FreshBooks believe the rewards are so worth it.

Look, the working world has changed with the growth of the internet, there has never been more opportunities for the self-employed. To meet this need FreshBooks is excited to announce the launch of an all new version of their cloud accounting software. It’s been redesigned from the ground up. It’s custom built for exactly the way you work. Get ready for the simplest way to be more productive, organized, and most importantly, get paid quickly.

The all new FreshBooks is not only ridiculously easy to use, it’s also packed full of powerful features such as, create and send professional-looking invoices in less than 30 seconds. Set up online payments with just a couple of clicks, and get paid up to four days faster.

See when your client has seen your invoice, and put an end to all the guessing games. FreshBooks is offering a 30-day unrestricted free trial to my listeners. To claim it, just go to freshbooks.com/meb and enter “The Meb Faber Show” in the “How’d you hear about us?” section. Again, that’s freshbooks.com/meb and now back to the show.

Jeff: All right, well we’ll hop into some reader Q & A questions then. This actually is appropriate because you touched on market cap a few times earlier. The question is, “Meb suggested several times that almost anything, any systematic index selection method is better than a cap weighted index. If so, why has so much of the index fund industry stayed with market cap weighting. What is Meb seeing that others are not?

Meb: Market cap weighting is the market, and so if you put together all the other strategies you end up with market cap weighting. And let me restate that. Market cap weighting is not…Anything other than market cap weighting is not better. There’s plenty of strategies that are way worse than market cap weighting. So investing in expensive stocks is way worse than marketing cap weighting. Investing in, you know, kind of a lot of the opposite factors are way worse ways to invest, than market cap weighting.

Market cap weighting is totally fine. It’s fine.

Jeff: Really?

Meb: It like your parents you know, coming home, going on a date or saying your boyfriend or your friend yeah, it’s fine. You know? So it’s like, it’s average, it’s okay. But if you sort it by almost everything else, if you sort by value. If you sort by multifactor, if you sort equal weight, you know, if you just buy the top 500 stocks equal weighted instead of market cap weighted it should be better. And the reason being, we’ve talked about this a lot. Market cap weighting no tethered [SP] value so you end up with a lot of the biggest companies being more expensive just because it’s price based. It’s a momentum strategy. So it’s fine, but it’s not the best that you could do.

So I think almost any strategy that, within reason, that makes sense is gonna be better. And will add, you know, a 100, 200 basis points depending on what it is, 50 to 200 basis points depending on what it is, and depending on how concentrated you get. The problem is a lot of these funds say they’re doing something different and then are basically closet indexers. We talked about this a lot. Where they basically look exactly like the S&P 500.

So you got to give yourself a chance, particularly if you’re gonna pay more than five basis points for that because, otherwise, if you’re gonna market cap weight, you can pay five basis points. And the reason why, you said, why do people do it? It’s an infinite scale. So you can manage $50 billion dollars, no sweat, with market cap, or more. But if you’re gonna be different, you have to be really different. And so there’s a lot of tools out there that we’ve mentioned in the past, so it’s on active share. West has probably my favorite at Alpha Architect. Where you can type in a fund or a ticket [SP] and it will show you just how concentrated and exposed to a factor it is.

There was a podcast Bill Miller, Legg Mason and Barry Ritholtz that’s a really, really good podcast. Where the common phrase is that passive is like a third of the industry. But Bill Miller said, look if you include the closet indexers it’s more like 70%. So the companies, the funds they end up looking up exactly like the S&P no matter what. So you want something really concentrated and really different if your gonna pay more than the 10 basis points these these low cost beta funds charge.

Jeff: So take that answer, let’s tie in one of your tweets the week in which you reference a chart showing the weight of the top 10 largest stocks in the S&P. And those weightings are currently near all-time lows, compared to historical weighting averages. So, does this lend itself to the idea that flaws and market cap weighting can ebb and flow in their intensity? Based on how much of the top stocks and the index, how much they command of that index from like a weighting perspective?

Meb: Yeah, if you look at times when market cap weighted index is particularly bubblicious [SP] like ’99, you know, your times…What? That’s a word, isn’t it?

Jeff: What’s that word…

Meb: And you also have to be careful. Obviously the U.S. is one of the biggest markets in the world. But if you look at some small countries you’ll have one stock being one fifth or a quarter of the index. Right? So it can get particularly distorted in countries and sectors where one company is like 10% or 20% or 30% of an index. But in the U.S. it’s usually quite a bit more diversified. And you rarely see a company, at something like the 4% rule. If you see a company pop its head above 4% in the U.S., it’s like the Madden Jinx, you know like where the Madden video game. If you’re on the cover, it’s like you’re gonna get hurt the next year. It’s like, if you’re a company and you hit this 4% in the U.S., historically it’s like your stock is about to get taken to the wood shed.

Jeff: Who is it we had on who was disgusted that Apple had crossed the threshhold?

Meb: I think it was Ramsey from Leuthhold, I could be wrong. But I mean there’s no reason for that to be a hard and fast rule, other than just market cap in general is tough because of the creative destruction. When you’re making a ton of money and you’re one of the biggest companies in the U.S. and you’re successful, with high profit margins, like, someone else wants that too.

So one of my favorite take aways of markets in general, is the super-high turnover. Like, so that if you look at the top 10 companies each decade, you know, it’s a different list almost every time. And the attrition rate of companies is so high, where there is so much turnover of companies dying and failing.

And it’s the same way with dynastic wealth for people. So, the Rothschilds of the world are probably huge outliers versus so many families, or companies that have high wealth and it goes away.

I was reading a stat somewhere, I took a picture on my phone, where it said something like 90% of high net-worth families, you know, over the next generation it ends up not sustaining. That seems high to me, but anyway. But it’s the same thing with companies, you know, but that’s a beautiful part of our capitalism, and that’s the way that it should be.

Jeff: Do you think that’s based upon is that an individual company level and they can be fantastic or terrible all on themselves…

Meb: [inaudible 00:36:21]

Jeff: …or do you think this is based upon industries that go in and out of favor?

Meb: Well, think like classic examples is buggy whips [SP]. So it changes. In 50 years from now probably 10 years from now talking about the industry of augmented reality stocks. Two years from now we’ve got marijuana index stocks.

Jeff: That’s kind of where I was going, was thinking about the potential exponential growth in tech that’s ahead of us, the next decade, two decades. You know, to what degree when you’re looking at, it’s a smaller sub-segment of the market. But when you’re looking at like U.S. stocks and if you’re not going up to straight to value play [SP], to what degree would you want to say all right I want to really hone in on tech, on sort of the cutting edge?

Meb: I got one word for you Jeff. Plastics. You know, so like each generation maybe, if you think back to all the revolutionary technology and ideas, I mean think about radio, and TV, and space flight, and plastics, and everything else. I mean, what it will be 10, 20, 30 years from now? Who knows?

Thematic [SP] is tough because thematic, I mean, if you were to ask listeners, “Listeners, what do you think the best performing sector of all time is?” You’re listening or actually it’s industry it’s not a sector, there is only about 10 sectors, but a hundred and some industries. Tobacco, right? The most boring non-tech industry of all time, but it’s trounced everything else.

From an investment standpoint people love thematics for some reason. I mean if you look at a lot of this thematic ETFS like hack or the cyber security that people…because it’s a good story and it’s something they can kind of attach to. But as we all know, there’s a massive difference between a stock and/or a sector. Sorry a business and sector and a stock.

You know, a stock, you want something that generates a ton of cash flows, and is probably cheap. A company and a sector, you want something totally different. But people get attached to certain ideas and concepts over time, and again those also wax and wane. At various periods in history people want different things. And late ’90s it was tech, and in mid 2000s it was commodity and real estate and dividend stocks. And this cycle, something different. Yada, yada, on and on.

Jeff: Why don’t you launch a vice fund? You know, tobacco, alcohol.

Meb: Because in general I don’t think that thematic investments are a good idea, you know, so…

Jeff: Tobacco is the best performing industy of all time.

Meb: Right. And hindsight…And so, one is that if you and again those are industries, so they are small by definition. And it’s fun, and it’s interesting to give people that choice. But it’s not the best investment approach. Right?

Why would you limit yourself just to one sector or industry but as a part of a whole portfolio. And then, and say, “Well, would you market cap the tobacco sector? Or would you use a multi-factor value composit? All these things. But in investing you want as much breadth as possible. You want to be able to choose from 2,000, 5,000, 10,000 securitites. Because it gives you a much bigger universe. But thematic? Look, if you want to play around with 5% of your portfolio.

Jeff: That’s assuming though that, I mean you’re taking the decisions out of your investors’ hands and…

Meb: By the way…

Jeff: …and how about having sort of concentration let them diversify throughout their broader portfolio.

Meb: By the way, the multi-factor approach probably would have selected a lot of tobacco stocks. So by default you end up owning a bunch. But look, if people want to play around with thematic trading by cryptocurrencies and do it with small percentages of portfolios, fine with me. Or in your case, option trade.

Jeff: Love [SP] my options. By the way I don’t know if you saw it, speaking of tobacco and alcohol. George Clooney, they sold Casamigos today for $700 million, potentially $1 billion with….

Meb: This is an article I would like to write with you, and we talked about, I thought about this when I saw that. Is we talk a lot about the huge difference between building wealth, so getting rich and staying rich.

So we often say asset allocation, a lot of stuff we talk about on this podcast is in the later bucket. It is about staying rich. And building wealth and getting rich, usually require some form of concentration. So it’s starting a business, or having a highly concentrated investment, or something like that.

Jeff: Combined Bitcoin and Ethereum.

Meb: You could, I mean theoretically you could, with the janitor where you live a lifetime, save and invest, and eventually you’ll get wealthy. But if you’re looking for say, you know, kind of an exponential or more shortened time frame, how to build wealth it’s owning a company or owning the cash flows, right? Or building it or concentration.

So I think a really fun article, say let’s look at the top 20 producing celebrities or entertainers. Right? And say, of their net worth how much of it was from their art, and how much of it was from the business? I mean, I could just name 10 off hand, so P. Diddy, Sean Combs, just sold part of his clothing line for 100s of billions. Dre, made a ton of his money off, not his records but the beats partnership. 50 Cent with vitamin water. What’s his name? Paul Mitchell, the hair guy, made more money off his tequila brand.

Meb: What was his?

Jeff: His was, it’s a really famous one. It might even be Don Julio. I can’t remember but so really famous entrepreneur and probably made good money off shampoo but he was like, “I made way more money of tequila than hair products.” So many examples. And the classic example, of course is athletes with endorsements. You know, so their brand can, and a lot of people are learning this. Their brand they parlay into business. So they become…Kim Kadashian’s sex tape but she made probably most of her money off of her app game, does some ridiculous amount of revenue.

Jeff: I mean store back [SP] real estate.

Meb: Really? For the listeners under 40, Jeff is talking about an old football player. But it’s probably a, it would be a really fun article and it’s a really interesting take away. And I think it says a lot about brand, but also says a lot about business. And you really want to be owning businesses and being a part of…I mean, Dan Acroyd, he had a pretty famous vodka.

Jeff: All right so this brings up an interesting point, is we talk about sort of traditional asset allocation. To what extent should a younger investor be specifically designating a larger than usual percentage of their portfolio, to go into private placements, or something that can really significantly increase your portfolio, versus just the Oracles of the world.

Meb: I think you can do that but, you’re saying, kind of, don’t limit your universe to just public companies. And so here’s the challenge on a couple of things. I’ve a number of comments. One is that, think about owning Amazon which is one of the best performing stocks, but public and you’ve had multiple 50% draw downs. We just wrote an article talking about it had, I think, a 90% draw down in the tech bubble.

So, despite owning one of the best performing stocks of all time, you had to sit through 50% to 90% losses, and how many people can do that? Very little. So private, the benefit of private, either being involved as a founding employee or investor is usually, you’re kind of locked up. So you can’t trade it, even if you wanted to. And it’s not market to market so you may get an update once a year, or every three or five years. And I think that a pretty interesting area.

And so going back to an area I had actually never heard of, that was really interesting to me was this concept of search funds. And so Patrick, and we mentioned him again on Invest for the Best. He did a couple of interviews with some Harvard professors.

Then there was a handful, there’s about half a dozen schools where they’ll teach, even if it’s undergrad or MBA, younger investors. But plenty are in their 30 or 40s now, basically how to search for a local national business so something like a cleaner company, or a company that supplies, you know, makes bread in Vermont that trades for four times earnings. That you could come into and potentially grow or modernize and make a very healthy return on investment.

So there’s a number of ways to do that on top of…I mean, I’m a classic example. You know my net worth is 90% dominated by Cambria. But it’s a company that I’ve built concentrated wealth, in the sense that it’s, you know, been doing it for a decade and everything else and…

Jeff: It’s gonna be weird when I take over your position and boot you.

Meb: Yes, and the uber. What’s that guy’s name just got booted? They have like top six of the executive is unfilled at that point. I’m a Lyft shareholder so I’m happy to hear this. This isn’t to say that you can’t grow wealth with a diversified portfolio, but by definition diversified portfolio in general is meant to keep up with inflation and grow it some. But the whole key there, is super-long time period.

So if you’re 20 you can utilize that long time period, compound it 5% real and eventually get wealthy. But if you’re looking for more kind of an outside exponential get rich, then it’s owning some sort of business. And a lot of people have done it in real estate too. But that’s the same sort of concept, where you’re buying into apartments, or buildings that then you’re leasing out and renting and getting cash flows so…

Jeff: To what figure do you think most investors don’t fully grasp that, that they get in the market and they think [crosstalk]…

Meb: I think this is a lot. And so because you’re seduced by the high return numbers I mean think about a high school. Just the compounding. If you just start with a $100 by the time you’re 50 you will have $10 million dollars in a type of chart. You know, like, “Whoa, if I just do that …” and that’s true you know, I mean the numbers don’t lie. I mean they say, “All right. Well, picture half of this going away three times.”

There was an investment book, I’m going to blank on who the name was, where he advocated…he said, “Look actually if you’re a young person the correct investment is a two time leveraged version of stocks.” And on paper that probably is the best investment. But you’ll have to sit through potentially losing 99% of your money, at some point.

And most people can’t because, most people can’t…It’s just too hard. It’s not…anyway. So, but I think we should update that. I think it will be a fun article to write. And an inside article to write will also be like, how to grow money, how the best celebrities and entertainers have built wealth, and also the aside is, how many have imploded it. Because so many are so…I mean there was ESPN 30 for 30 on a laundry list of entertainers that have made tens, if not hundreds of millions of dollars and are bankrupt. You know, Mike Tyson and Allen Iverson. There is, like, a gazillion and it’s because people extrapolate, you know, certainly how much money they have, indefinitely, into the future.

Jeff: There’s also a lot of bad advisers who get them into things like, what was it? Something that [crosstalk]…

Meb: Very predatory too.

Jeff: Yeah, well you always have your harem who’s sort of surrounding you, just leeching you off you until the money dries up.

Meb: But you know you read about so many. I mean I was reading Tim Duncan, people always get in the press like suing their adviser for putting them into a solar of panel deal in Wyoming and meanwhile they got paid 5% percent to put you in the deal and it’s just…the vast majority of like, I’m surprised the NFL, all the major sports, NHL, baseball and everything says you know what? and they probably have this, I don’t know.

We’re setting up a deferred…you’re gonna have a…if I was a robo adviser listening to this, I would say, we’re gonna go pitch all these sports leagues and say, “You sign up, you’re going to get automated investing solution for 25 basis points.” But, you know what they need? They need the forever fund. “You’re gonna get locked up and you can’t spend this.” My favorite is, was it Bobby Bonilla who, when he negotiated his contract, says, “No, no, no. I don’t want a huge up-front payment, but you’re gonna pay me $1 million for the rest of my life.” So the Mets have to pay him still. It’s like $1 million forever, I think. Which is a brilliant move because you know, anyway, we’re just ranting at this point.

Jeff: I do want to write the article with you about the sort of entrepreneurial, start-your-own-business type activities. And I think that is the way to real wealth, far faster. And I think so many investors get it wrong.

Meb: It’s a lot of work too, but like you mentioned also investing in private companies. So a classic example is arguably the best performing venture fund of all time. Which was Chris Sacca’s Lowercase Capital, where he was an early investor in Uber and Twitter. And it’s fun to read his history because he had times before that, where essentially, highly leveraged kind of almost went broke sort of thing. So a couple of times in debt. But, and I feel like there’s 1,000 stories where the opposite of people did, tried to do what Chris Sacca did and went to zero, right? Lost all their money.

But highly concentrated, highly knowledgeable and Buffett talked a lot about this. Instead of putting your eggs, all in a basket pick a couple of eggs and watch that basket. Where if you can pick private companies and do an enormous amount of research, and have more either information or a better understanding or whatever, and concentrate in those companies, that’s an awesome way to build wealth. But it’s a ton of work and it’s hugely different outcomes, like it’s concentrated. It’s tough. It’s hard.

Jeff: I mean that’d be an interesting show, is, what’s the appropriate due diligence required for researching private companies. How do you really know? I think that’s a world a lot of people don’t really know much about.

Meb: No it’s hard. Check out Patrick’s episode for the search funds and then the Harvard guys put out a book, we’ll put it in the show notes, on basically how to do search funds and there was actually like a dozen funds that invest in this young entrepreneurs.

So there’re search fund, funds where you can actually invest in a search fund that’ll invest in a diversified group of these young guys. The problem with those though, is they don’t have any potential liquidity really. So if you like, buy a bread company in Vermont, like, who are you going to sell to in five years? Same sort of thing.

Jeff: Also, if it’s a fund to fund you’re not necessarily getting the concentration risk that you need.

Meb: So it’s good in that way but it’s because these are targeting…so yes and no. Anyway, let’s move on.

Jeff: Yeah, whatever.

Meb: All right next, read the question okay, I still can’t wrap my head around how to use commodities and portfolio. The IV portfolio promotes putting 20% in a broad commodity index in the podcast I’ve heard you discussed the financialization of commodities futures leading to loss of roll [SP] yield. So what’s the answer here? Include commodities as an inflation hedge but be prepared to pay the price of long term drag. Or forget about commodities and just focus on stocks, bonds, real estate?

Jeff: We’ve long been proponents of commodities as the general mood on commodities certainly gets pretty extreme at times, mid 2000 oil 150, you know, every institution endowment on the planet loved commodities.

Meb: Do you have any current thoughts on oil right now?

Jeff: Hold on. And now like you see all the institutions divesting commodities. Harvard’s now selling all their goats in New Zealand. You know it goes through, the same thing we’ve talked about earlier. Ebbs and flows on commodities in general. You know, I think a long only approach is fine, I think a long-short or long-flat approach is also fine. I think Ray Dalio, largest hedge fund in the world often says, we talked about him on a prior episode, “If you don’t own gold you understand neither history or economics.” And I think in his allocation he proposed like owning 15% in gold or something.

Anyway, so implementation is well there was the first generation commodity indices which weren’t necessarily optimal. So they didn’t take into account roll yield and all this other things. So most commodity investments happen through futures. So listeners, you can think about you buy commodity contract, future contracts that, say, expire quarterly out into the future. And depending on demand you could have a situation where they’re either in backwardation [SP] which is, the future commodity prices are lower than the current contract, or contango, which is they are higher.

And so if you buy them in certain ways that roll yield is either positive or negative in your favor. And historically a lot of the critics say, well look, the roll yield historically was in your favor but now, over time it’s different or it changes and that’s partially true because money’s come in, but also you can devise industries that will take advantage of that, instead of being just kind of dumb.

So there’s all these new 2.0 versions of commodity funds and industries that have better or more optimal role strategies that I think helps. But in general, I mean commodities is something that you really, kinda need to see unexpected or just inflation in general, that’s where they shine. Particularly gold. You know either of those types of environments. So I see diversified as part of the portfolio. How much? That’s kind of up to you. Our Canadian listeners probably have a lot more. Or Aussie listeners have a lot more. But I definitely think it’s a reasonable portion.

Jeff: Do you do any research personally in to, I mean, back to the idea of oil on it’s plunging right now. Do you follow oil, or gold, or anything else, with more specific interest?

Jeff: You know it’s often very commodity specific. We know we just man, some old posts where we looked at a lot of economic factors, on asset classes and you know, gold, for example. It’s widely known that it loves negative real interest [SP] rates. That’s when gold particularly does great, where inflation is higher than current interest rates. Trend volume works great, of course, you know we showed that many times in the past, gold, and other commodities. But the market for weed is gonna look totally different than the market from cotton which looks different…you know, and there’s there’s so much…and there’s also no insider trading. Remember like commodity, if you’re Cargill or you’re one of this huge producers, you definitely have more information than everyone else does.

And so trying to predict fundamentals base, I think, will be really tough in commodities and oil, there’s a great…God I’m gonna blank on this quote. Man it’s so good to…we’ll try to post it in the show notes. While you talk about the next question I’ll see if I can find it. But it’s basically Exxon’s CEO or ex-CEO talking about oil prices, and basically how it’s impossible to forecast.

Oil prices Exxon CEO I’ll see if I can find anything but it’s tough. I mean, and the beauty of commodities too is you have so much of this, it’s like econ 101. The cure for high oil prices is high oil prices [SP]. Where, all of a sudden you have these new technologies come on, and all of a sudden, you know, people extrapolate it in the future where oil prices are going up to a $1,000 and yada, yada, we’re running out of oil. Well, guess what? People, say, “Damn, I can make a lot of money with oil at $100.” And they invent fracking and then all of a sudden nat gas gets hugely competitive and wind and solar. You know so all of this things have…science kinda takes over, and which is great and that’s the way that…

Meb: Free market economics.

Jeff: Free market.

Meb: All right next question. Please explain the difference between the unadvised practice of performance chasing, and the highly encouraged practice of momentum investing.

Jeff: I think there’s a pretty key difference and that is performance chasing has no rules based approach.

Meb: So usually people’s performance chasing, they find a hot sector, they buy it, so they have one. Usually no buyer methodology other than their neighbor or what they read in the newspaper, but more importantly, way more importantly is they have no sell methodology. So usually they sell it when it goes down by 50% or something.

So momentum, at least you have buy and sell rules, that doesn’t mean it always works. But you have rules to take advantage of, “When do I get in? When do I get out?” Same with trend following. Entry is one of the least, usually, the least helpful. But novice traders most interested in entry. “I want to pick the top. I want to buy the bottom.” But then they have no exit.

They, like, they don’t have a process for selling, and that’s way more important. I mean I’ve seen research that you can build profitable trading systems with random entries. Because you have, certain sort of sell rules that are trend following or whatever they may be.

So I think performance chasing is, you don’t have a system, but that could also be extrapolated to a lot of types of investing.

Jeff: One of my biggest fears with trend momentum is just…

Meb: I just want you to stop there. What are your biggest fears, Jeff?

Jeff: We don’t have time for that on this show. Just getting whipsawed around. So I’m curious to what extent, I mean the 10 month SMA is pretty well known, pretty well followed, if you’re doing trend momentum. To what extent though have you or people in the business back tested tons of different time frames and decided upon the best. Why is the 10 months, sort of, the go-to? Is there a better optimum time frame to not get whipsawed out?

Meb: There is a better optimal one, but problem is it won’t be the most optimal one in the future, or unlikely to be the most optimal. So you want to try to find what you would call parameter stability. And so back in our old ’06 white paper we said, 10 month moving average wasn’t the best return of risk across any of the parameters. But it was in the middle. So you could certainly use 3, 4, 8, 10, 12, 14 months and probably be just as fun. Fifty day, 200 day whatever it may be because you’re still capturing the same thing. And I think it’s totally reasonable to use multiple measures. So you could theoretically use, you know, the 50 day, the 200 day, and the 300 day. Scale in and out 30% each of your position and that gives you the blended average of all of them.

So you see this a lot with CTAs where they use maybe like a dozen trend following systems where one may be a one range break out. One may be a trend following, one may be…So you end up capturing the same stuff but it’s not a binary outcome. You know, if you do a trend following with just 200 day on U.S. stocks, like we said earlier, you are either all in or all out on the 1987 crash. But maybe if you use two or three or five of them. The problem for most people is it gets complex. But it’s too much…

Jeff: Well, I was about to say, do you buy into that? Because what that makes me think of is Jayson Sue’s [SP] article, in which he talks about the fishing lures. Where you have the wooden one that did just as well…

Meb: I think the worst thing to do would be to have one and then when it stops working switch to whichever one is working today. So I think having a blended average trading as many markets as possible, trend following is the whole point. So we’ve had a lot of CTAs on the podcast in the past and a lot of this guys will trade 50, 100 plus markets. So that’s the really key way to diversify, is you can diversify across indicators, but you can also diversify cross markets.

Jeff: All right next question. Potentially the last one.

Meb: Hopefully. we have some lunch here. We have Goan food. Have you ever had Goan food?

Jeff: Do you want to explain what that is?

Meb: It’s Indian. It’s kind of sea-food centric but sea food doesn’t really travel well with delivery so I think we got a lot more veggie and chicken.

Jeff: Are you as a chef by the way. I feel like you’ve cooked once or twice and it’s been pretty questionable.

Meb: I know I cook a lot, and it’s…I like to experiment. My way of cooking is, I rip out recipes or find recipes. I’ll put them in a book and will cook them once and then I throw them away. So that’s my method to kind of teach myself so it’s everything from roasting, baking, sous vide, frying, grilling, you name it right. And so there’s a lot of experimentation.

Jeff: And I’m regretting asking this question.

Meb: I know hold on, I’m almost done. And so if I cook something that ends up with a recipe that’s like all world, I’ll save it. But I only have about five of those. And I was reviewing it the other day. One was like a bagel breakfast casserole. Where you like chop up bagels, put it in a casserole dish. Listeners, Jeff likes anything casserole or crock-pot related. So if you have a crock pot recipe send…

Jeff: Yeah, send the crock-pot recipes.

Meb. …Jeff makes the same one every single week.

Jeff: I got a couple.

Meb: And then the one I just made was some sort of like roasted potato with tomatoes and fetta just like basic stuff. But like going back to the sous vide. I have a new sous vide now the

Anova, which is great. Because you don’t have your own dedicated sous vide-ing machine and I would say half of it comes out good. A quarter comes out amazing and a quarter is basically, like inedible, like it’s really bad.

Jeff: I must have been there on one of the inedible nights with you.

Meb: And maybe it’s a quarter. Like a third is just kind of like… and my problem is that as a chef I am more like my mom, where it’s just like tablespoon and I will just grab a handful of salt. So I’m particularly bad at baking because it’s a lot more exacting. And I made some biscuits the other day which were like the most…they were like bricks. But the good news is we have…

Jeff: All right, you’ve rambled on long enough about this.

Jeff: We have a dog that’s likes eating leftovers so he gets a lot of snacks.

Meb: Ties this back to one last markets question here. Right, I want to know your thoughts on implementing life-style glide paths for an individual or client’s portfolio. Quant style approach looks at risk a lot different than most, but I do see value in reducing portfolio risk, as you come closer to withdrawing money. The question is, which risk or which approach do you use, to reduce the risk? Regarding your trinity [SP] style approach, does that mean reducing from say a trinity five to a trinity three, a couple years prior to retirement? Your thoughts?

Jeff: Yeah, I mean this is under the category of not a strong opinion. I think it’s fine I think just adding more on bonds and fixed income as you get older are totally fine. If you want less volatility, I mean the big problem there is, you know, a lot of people…You got to include the human capital, which means do you have any other sort of income. Do you have social security and pension because those are very bond-like investments.

So theoretically if you have pretty cushy income elsewhere, you don’t want to double down on more bond-like income, probably. So it’s a lot of factors and I think this is where a number of advisors really are helpful and you’ll see the robo platforms eventually incorporate a lot of this where, you know, it’s very situation specific. So for a lot of people, and you know, I think it’s fine but for some people I think it needs to be totally dialed in differently.

Jeff: Who was it we had on who was discussing how we’re going to live until 120?

Meb: Edelman.[SP]

Jeff: Edelman. To what extent, I mean did you buy into a lot on that and does that change the way that you potentially see asset allocation as you’re getting older? Because we’re sort of operating on this false premise that we’re gonna be outta here at 80 to 90 where in fact our morning is gonna last another two to three decades.

Meb: I feel like my life style in adventuring puts me in a much higher risk of the not living forever category. I feel like the way I’m gonna go is probably not.

Jeff: The cooking you describe…that puts you [inaudible 01:05:02]

Jeff: Probably not yeah. And meanwhile we cooked last night and got food poisoning so, FYI. Well I didn’t get it I don’t know, I think just the common senses expect to live longer. Whether that’s 80 or 120 I don’t know.

Jeff: Well, start a new business, get back to our entrepreneurial…

Meb: This podcast is falling apart it’s been too long since we’ve had calories. Anything else or do you want to call it?

Jeff: You want to discuss Risk Allies [SP]?

Meb: Oh, yeah, we can. We launched, our company launched a new offering. If you still made it to this point. I doubt that there’s four people on air. If you’re an adviser and want to partner with us to do an automated investing solution, we just launched one, partnered with Risk Allies. We’re a founding… Founding is the wrong word, we’re an initial launch partner with them where you can allocate to Cambria Trinity Strategies, and for more information just go to Risk Allies and look up their auto pilot feature or email or call them, or us, for more info.

Jeff: Works.

Meb: Cool.

Jeff: All right, take us out.

Meb: All right, I’m going to be doing some traveling if you find yourself in San Francisco in New York, Amsterdam, Orlando and maybe one other, I can’t remember, come say hello. Thanks for listening today. Feedback, send Jeff questions at feedback@themebfeberfabershow.com. You can always find the show notes and other episodes at mebfaber.com/podcast.

Subscribe to the show on iTunes, if you’re enjoying the podcast leave us a review. Thanks for listening friends and good investing.

[01:06:38]

[music]

[01:06:42]

Sponsor: Today’s podcast is sponsored by The Idea Farm. Do you want the same investing edge at the pros? The Idea Farm gives small investors the same market research usually reserved for only the world’s largest institutions, funds, and money managers. These are reports from some of the most respected research shops in investing. Many of them cost thousands and are only available to institutions or investment professionals. But now they are yours with The Idea Farm subscription. Are you ready for an investing edge? Visit theideafarm.com to learn more.

[01:07:10]

[music]

[01:07:31]

.