Episode #60: William Bernstein, Efficient Frontier, “The More Comfortable You Are Buying Something, In General, The Worse The Investment It’s Going To Be”

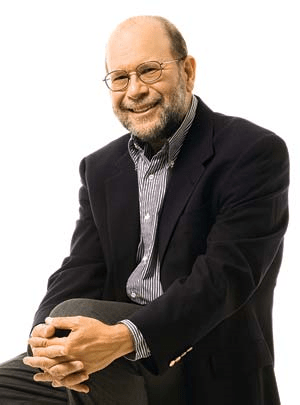

Guest: William (Bill) Bernstein is a financial theorist, a neurologist, and a financial adviser to high net worth individuals. Known for his website on asset allocation and portfolio theory, Efficient Frontier, Bill is also a co-principal in the money management firm Efficient Frontier Advisors. He has also authored several best-selling books on finance and history, and is often quoted in the national financial media.

Date Recorded: 6/28/17 | Run-Time: 58:01

Summary: Bill starts by giving us some background on how he evolved from medicine to finance. In short, faced with his own retirement, he knew he had to learn to invest. So he studied, which shaped own thoughts on the matter, which led to him writing investing books, which resulted in interest from the press and retail investors, which steered him into money management.

After this background info, Meb jumps in, using one of Bill’s books “If You Can,” as a framework. Meb chose this as it starts with a quote Meb loves: “Would you believe me if I told you that there’s an investment strategy that a seven-year-old could understand, will take you fifteen minutes of work per year, outperform 90 percent of financial professionals in the long run, and make you a millionaire over time?”

The challenge is the “if” in the title. Of course, there are several hurdles to “if” which Meb uses as the backbone of the interview.

Hurdle 1: “People spend too much money.” Bill gives us his thoughts on how it’s very hard for a large portion of the population to save. We live in a consumerist, debt-ridden culture that makes savings challenging. Meb and Bill discuss debt, the “latte theory,” and the stat about how roughly half of the population couldn’t get their hands on $500 for an emergency.

Hurdle 2: “You need an adequate understanding of what finance is all about.” Bill talks about the Gordon Equation, and how investors need an understanding of what they can realistically expect from stocks and bonds – in essence, you really need to understand the risks.

Meb steers the conversation toward investor expectations – referencing polls on expected returns, which are usually pegged around 10%. Using the Gordon Equation, Bill’s forecast comes in well-below this (you’ll have to listen to see how low). The takeaway? Savings are all the more important since future returns are likely to be lower.

This leads to a great conversation on valuation and bubbles. You might be surprised at how Bill views equity valuations here in the U.S. in the context of historical valuation levels. Bill tells us to look around: Is everyone talking about making fortunes in stocks? Or quitting good jobs to day trade? We don’t see any of these things right now. He’s not terribly concerned about valuations.

Hurdle 3: “Learning the basics of financial and market history.” Meb asks which market our current one resembles most from the past. Bill tells us it’s a bit of a blend of two periods. This leads to a good discussion on how higher returns are more likely to be coming from emerging markets than the U.S.

Hurdle 4: “Overcoming your biggest enemy – the face in the mirror.” It’s pretty common knowledge – we’re not wired to be good investors. So Meb asks the simple question why? And are there any hacks for overcoming it? Or must we all learn the hard way?

Unfortunately, Bill thinks we just have to learn the hard way. He tells us “The more comfortable you are buying something, in general, the worse the investment it’s going to be.”

Bill goes on to discuss the challenge of overconfidence and the Dunning Kruger effect (there’s an inverse correlation between competence and belief one has in their competence). Meb asks if there’s one behavioral bias that’s the most destructive. Bill answers with overestimating your own risk tolerance. You can model your portfolio dropping 30% and think you can handle it, but in when it’s happening in real time, it feels 100% worse than how you anticipated it would.

Hurdle 5: “Recognize the monsters that populate the financial industry.” Basically, watch out for all the financial leeches who exist to separate you from your money. Bill tells us a great story about being on hold with a big brokerage, and the “financial porn” to which he was subjected as he waited.

There’s way more in this episode: Bill’s thoughts on robos… What Bill thinks about any strategy that moves away from market cap weighting (Bill thinks “smart beta” is basically “smart marketing”)… How buying a home really may not be a great investment after all… Cryptocurrencies… and even Meb’s “secret weapon” of investing.

Sponsors:

- Soothe – Massage delivered to you. Enter code MEB for $20 off!

- Lyft – Request a ride and you’ll be on your way in minutes. Request. Ride. Repeat.

Comments or suggestions? Email us Feedback@TheMebFaberShow.com or call us to leave a voicemail at 323 834 9159

Interested in sponsoring an episode? Email Jeff at jr@cambriainvestments.com

Links from the Episode:

- Efficient Frontier website

- Bill’s books on Amazon

- The Dunning-Kruger effect

- 4:32 – “If You Can”

- 10:23 – Episode #54: Elizabeth Dunn

- 12:48 / 15:56 – The Gordon Equation

- 21:00 – Dow 36,000 (Book)

- 22:30 – Common Sense on Mutual Funds (Book)

- 25:20 – Devil Take the Hindmost (Book)

- 25:20 – The Great Depression: A Diary (Book)

- 26:00 – Triumph of the Optimists (Book)

- 29:47 – The Dunning-Kruger effect

- 34:29 – Your Money and Your Brain (Book)

- 42:13 – How a Second-Grader Beats Wall Street (Book)

- 42:17 – All About Asset Allocation (Book)

- 55:11 – The Great Leveler (Book)

- 55:55 – Tatiana’s Sex Advice to All Creation

Transcript of Episode 60:

Welcome Message: Welcome to “The Meb Faber Show,” where the focus is on helping you grow and preserve your wealth. Join us as we discuss the craft of investing and uncover new and profitable ideas, all to help you grow wealthier and wiser. Better investing starts here.

Disclaimer: Meb Faber is the Co-founder and Chief Investment Officer at Cambria Investment Management. Due to industry regulations, he will not discuss any of Cambria’s funds on this podcast. All opinions expressed by podcast participants are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of Cambria Investment Management or its affiliates. For more information, visit cambriainvestments.com.

Sponsor: This podcast is sponsored by the Soothe app. We all know how stressful investing in volatile markets can be, that’s why I use Soothe. Soothe delivers five-star certified massage therapists to your home, office or hotel in as little as an hour. They bring everything you need for a relaxing spa experience without the hassle of traveling to a spa. Podcast listeners can enjoy $30 bucks to their first Soothe massage with the promo code ‘Meb.’ Just download the Soothe app and insert the code before booking. Happy relaxation.

Meb: Welcome podcast listeners, we are very excited today. By the time this podcast comes out, I will officially be 40. This is my last podcast in my 30s, so to celebrate we thought we would have the great William Bernstein. Bill, welcome to the show.

William: Glad to be here.

Meb: Bill’s chatting with us from Oregon, and for those who aren’t familiar, Bill runs Efficient Frontier Advisors. This is an investment advisory firm, but also it started out as a practicing neurologist, also has a PhD in chemistry. You know, I had a biotech background, but not that involved.

Prolific writer, he’s written about 100 books by now. But Bill as we…just to get started before we dive into all the investments, for listeners who might not be as familiar with you, maybe give us just a short background on your history, and how you transitioned into the investing world.

William: Okay, happy to. Just one fast detail I always like to get out there, I’m not the manager of Efficient Frontier Advisors, I’m the co-manager. I have a partner, a lovely lady by the name of Susan Sharin.

The story of how I evolved from medicine into finance, as you might imagine, is kind of a shaggy-dog story, which is about 25, 30 years ago I realized that I lived in a country that didn’t have a functioning social welfare system. That I was responsible for my own retirement savings and my own retirement income, in large part, and so I was going to have to invest on my own. And I approached it the way I thought anyone with scientific training would do.

Which is, I read the peer-reviewed literature and the basic textbooks on the subject, and then I realized I was going to have to collect data and build the models. And by the time I was done with that process, which took, you know, a couple of years, I realized that I had acquired a knowledge base and some mathematical tools that were of use to other small investors.

And so I decided to write a book, and eventually the book got published, and when you publish finance books, reporters start calling on you, and people start asking you to manage their money. And then I segued into money management, and that got me segued into other fields as well. So that’s the short version of the story.

Meb: I thought we’d use one of your more recent books as a framework, and a lot of them have followed a similar path to varying degrees of complexity, and like you mention, your first book…certainly you mention a lot of the readers said, “Great book, Bill, but a little too complex for me.”

And so we actually just reread one of yours last week that’s…readers, it’s about 40 pages, so you can knock it out in about an hour, and it’s geared particularly towards younger investors, but the lessons are timeless, and it’s called, “If You Can.”

And I’d like to start out with a quote that you had in the beginning, and you said, “Would you believe me if I told you there’s an investment strategy that any 7-year-old could understand, will take you 15 minutes of work per year, outperform 90% of the investing pros, and make you a millionaire over time?” So I thought maybe you could give us a little insight into that strategy, and then we’ll jump off from there.

William: Okay. Well, just to give you some background, the trick with making $1 million is to have a long period of time to do it over, and so the book was aimed at young savers. Our firm manages money for older, high-net-worth investors and I thought it would be worthwhile for me to engage in an eleemosynary activity for younger people, to enable them to get started.

So I basically make this book available pretty much for free. It’s available as a free Acrobat download, and if you want it on your Kindle you’ll have to pay a dollar — because that’s what Amazon makes me do.

The strategy is very simple, it’s just a simple three-fund…it’s called a three-fund portfolio in the biz, which is equal parts U.S. total stock market, foreign total stock market, and U.S. bond market, and you can do that for next to nothing, in expenses.

And if you have discipline to simply put that into your 401(k) plan, apply that strategy to your 401(k) plan, then you can save 15% [SP] of your portfolio, and you’ll wind up, at some point in the future, with $1 million. You know, you’ll have to adjust that down for inflation, it won’t be quite as good as it seems now, but it’ll be a solid start towards your retirement.

And the title comes from the fact that it’s very simple, and the hook there is that it’s simple but not easy. And the analogy I use is losing weight, all right? It’s extremely easy to lose weight, all you have to do is eat less and exercise more. But it’s not easy. And finance is the same way, investing is the same way — it is very simple, but it is not easy. And that’s what the book is about is, enables it to make it a little easier and a little more understandable.

Meb: That’s a great jumping-off point because I was going to joke and say, “All right, podcast over. Everyone, you have the allocation, you can just move on.” But that’s not really the challenge, and the keyword you talk about being in this book is the word ‘if.’ ‘If’ you can follow this simple proclamation.

We’re going to talk about today, you say there’s five hurdles, and it mirrors some of the other books where you talk about some similar, whether it’s four to five hurdles, challenges. And also there’s another phrase used, which I love, called “The Five Horsemen of the Personal Finance Apocalypse.” But I figured we’ll touch on all five here, and we’ll begin with, from a physician’s phrase probably, “Take your medicine,” with the first one being, people spend way too much money.

We just saw recent news today of an old Denver Broncos/Washington Redskins quarterback and all the trouble…excuse me, running back, Clinton Portis, and all the trouble he had, and got to the point of almost murdering his financial advisor. But we’ll talk about it. So it’s first, people spend way too much money. You wanna start there?

William: That’s half of the problem. I guess I’m going to reveal a little bit of my politics, which is that we also live in a society that doesn’t pay people very much for…in a lot of lines of work, and in a lot of places education and housing are so ridiculously expensive that it really is mathematically impossible for some people to save, and I think that that’s too bad.

The fact, I’m not sure you’ve heard this statistic, is that roughly half of the population couldn’t get their hands on $500 in cash to fix their car for — on an emergency basis, if they had to. And so that’s half the problem.

The other half is more of your control, which is that we live in this very corrosive, consumerist culture that tells you, you have to have the fanciest brand names in your shoes, and in your phones, and in your automobiles, and you have to live in a big house and you have to drive a Beemer. The key thing lies in understanding that it’s really not material possessions that make you happy.

A Beemer isn’t going to make you, in the long run, any happier than a Toyota. If you can buy an inexpensive Android phone, you’re going to be probably a lot better off than buying the latest Apple machine. It’s all part and parcel of that.

There is what’s called The Latte Theory, which gets derided but I still think there’s a certain amount of truth to it, and the Latte Theory is if you cut out that one latte you have every day, that winds up being close to $100 a month. And if you can save $100 a month and invest it well then, over time you’re going to have a fairly decent sized portfolio. Now the trick is, you really just can’t have one latte factor as a…it’s not a sufficient saving. You have to really have…you have to find five or six lattes in your life and cut them out. And that’s kind of the way I look at it. The easiest way that a young person can do that is to get a roommate. Cut out all six lattes at once by getting a roommate.

Meb: One of the interesting parts of this podcast that we talk…So much focus historically on investing and focusing on the investing side, but we’ve had a couple of people on, and in particular one was Elizabeth Dunn who talked about…she had a great book called “Happy Money,” been talking about a lot of the ways that people optimize on making money but maybe not think as much about spending. And if they’re really more thoughtful about the way they spend it, they could do a much better job of saving, as well as spending on the things…sorry, on, like, say, experiences versus things.

And there’s two quotes from your books that I love, particularly you are fondly speaking about your parents, and one where you said your dad had made a quote where you say, “Your neighbors owned a lot, but didn’t have a lot.” And then a follow-up one I loved, when you asked your parents, you said, “Are we rich?” And they said, “Your mother and I are comfortably well-to-do. You don’t have a dime.” Which I thought was really funny.

But your prescription was, you said, first of all, when you think about your own personal finance, is to get out of debt. And maybe talk quickly about that, and then we’ll start to move on to the next hurdle.

William: Well, I’m no expert in personal finance. Our firm, for example, doesn’t do financial planning, we just do investment management, but it’s fairly obvious that if you do have debt, you should consolidate it into the lowest interest rate you can, so for God’s sake, get rid of your credit card debt. Your educational loans probably have a much lower interest rate. You know, you can get rid of that later, if you can. And then finally, the last debt that you should get rid of is your mortgage because…if you have one, because after all, that’s got the lowest interest rate.

Meb: So, the cool part about this book, and Jeff and I have talked a lot about this, and the need for financial education and how it’s a shame that most high schools don’t teach personal finance, is that in this book Bill ends…each of the five chapters with a homework or book recommendation. So you’re supposed to read the book through, and then you go back and then you read these follow-on readings. And so his recommendation for this chapter was “The Millionaire Next Door,” by William Danko, but this will transition into this concept of, to really succeed as an investor you also need to understand some just finance basics.

I think it’s probably saying a lot, where so many of the people that we talk to…even professionals, don’t have a grounding. And so maybe if you could talk a little bit about…just gloss over the…kind of the basics of stocks and bonds, but more importantly, you talk about the Gordon Equation and kind of giving some idea of what you think some of the basics are, and why that’s important.

William: Well, yeah. I mean, the most important thing that you should have is some understanding of what you can actually expect from stocks and bonds. Stocks have to have higher returns than bonds. They must, over the very long-term, simply because they’re so much riskier than bonds.

And one of the things that comes up very frequently is people will say, “Well, I’ll take out a mortgage, because I can borrow that money at 3.5% or 4%, and I can make a lot more money on my portfolio.” Well, yes you can, but you are taking a heck of a lot more risk when you do that.

And it’s much smarter if you’ve got a mixed portfolio of stocks and bonds, and you’ve got a mortgage, to just pay off the mortgage with the bonds in the portfolio, and then you’ve basically accomplished the same thing at a much lower cost.

So that’s the first thing to understand, is just how risky stocks are. You can easily, on the very short-term, lose half of your money over a period of a year, or a year -and-a-half, as happened in between 2007 and 2009, and history teaches that there are even worse scenarios than that.

So, the money that you want to invest in stocks is the money that you shouldn’t need for at least 15 years. You know, 10, 15 years, at the very minimum. So that’s the first thing you really need to understand is the connection between risk and return. Anytime anybody tells you that they can give you high returns at no risk, that’s a fairly surefire sign of fraud.

Meb: Let’s talk a little bit about expectations, and I think this is super useful. I’ve been giving a couple of speeches lately where we cite a couple — State Street and then “Financial Times.” I mean, there’s three or four of these studies where they poll individuals as well as institutions, in the U.S. and around the world, and ask them what their expected returns for their portfolio as well as stocks, are. And almost always, without really much spread the number comes in around 10%.

I thought it might be useful for you to just kind of talk a little bit about expectations, maybe talk about your simple equation that you use for equity returns, and then how this balanced portfolio might perform. Because I think it’d be useful for people to hear it from the doctor on what a more reasonable expectation may be.

William: Yeah, you primed me with that five minutes ago and I didn’t bite, I wandered off. Sorry I did that. Well first of all, the return on a bond is very simple. The expected return on a high-grade bond is simply…it’s a coupon.

So the long treasury is yielding less than 3%, the five-year treasury is yielding less than 2% —that’s what you can expect, and that’s…even that 2% is not properly much more than a short-term rate of inflation. I think inflation’s, probably on the long-term, going to be higher, since that’s what it’s been historically.

Stocks are only a little more complicated, and there are many different ways of arriving at the Gordon Equation. It makes it sound complicated, the Gordon Equation isn’t complicated. It simply says that the expected return on a stock…on stocks is the dividend yield, which is 2%, plus the long-term dividend growth rate, which is probably around 5%. But in this low-inflation background of your environment, maybe it’s closer to 4%.

So you add 4% to 2%, and you get an expected 6% return, so if you have a mixed portfolio you average together 2% and 6%, and you get a return of 4%. And what that makes abysmally clear is that how good an investor you are, how successful you are in investing and saving, really depends far more upon how successful you are at saving than you are in investing. Your name could be Warren Buffett, and if you can’t save, you’re toast.

Meb: You know, there’s a huge gap between what Bill just talked about, and we talked about this a lot in the past, of this 4, 5, 6 nominal returns, versus what all these pension funds expect at 8%, and then these surveys of people expecting 10%.

One of the questions, I wasn’t gonna get into this now but I think it’s interesting, is that one way to…listeners to certainly deal with valuations and think about times when stocks may be expensive, is that you rebalance, and so that naturally has you selling what’s expensive and buying back into what’s cheap.

But a question I wanted to pose to you is, thinking about history and where markets have been, whether it’s Japan in the ’80s or the U.S. in the ’90s, and even…So Jack Bogle has similar comments about expected returns, you know, being lower and saving more.

I wonder, is there a valuation level where you would consider saying, “Common sense would dictate that we should be reducing our stock exposure, or perhaps reducing the bond exposure”? I know this is an area that a lot of people really struggle with. Is this something you’ve thought about or come up with any sort of takeaways? Or is the prescription just to buy and hold, and move on?

William: Yeah, I mean it’s something I’ve thought about more than a bit. You know, what Jack Bogle does is, he adds a third term, which is a term for regression to the mean. So he says, an evaluation’s really high, you should subtract some of that expected return out, and vice versa if valuation’s really low. And I think that there’s some merit to that.

The problem with that approach, is that you’re assuming that the past distribution of valuations is going to be the same as the future distribution of valuations. So for example, the Schiller CAPE is now close to 30, or is about 30, which is the most commonly-used measure of a valuation. The cyclically adjusted PE is what CAPE stands for, and that’s at about the 96 percentile, if I’ve got the number right.

So you would say, “Yeah, the market really looks overvalued.” But the trouble is, if it’s at the 96 percentile of values between 1871 and 2017, and things…you know, the world was a lot different place in the year 1871 than it is now. So maybe the value of 30 is not at 96 percentile, maybe for future values it’s closer to the 60th or 70th percentile. Which gets into what we were talking about before the call, which is how do you identify a really overvalued market?

And I think you do that more with sociological criteria than you do with firm econometric criteria. Rather than trying to look at all these numbers and figure out whether it’s outrageous or not, what you do is you simply look around you, and is everybody talking about stocks? Same thing goes for real estate, of course.

If you go to a party and everybody is talking about flipping real estate or is brokering mortgages, you can bet there is a real estate bubble. If you go to a party, as happened frequently during the late 1990s, and everybody is talking about how they’re getting rich in tech stocks. Particularly if they’re people who, in general, are not particularly well-rounded in finance or don’t have a background in it. Then that’s a sign of a bubble.

When people are quitting their jobs to day trade or broker mortgages, that’s the sign of a bubble. If you exhibit skepticism about the prospects for stocks, and people just don’t disagree with you, but they disagree with you vehemently and tell you you don’t get it, and that you’re an idiot for not understanding things or that you’re an old fogey, that’s the sign of a bubble.

And finally, another sign of a bubble is when you start to see extreme predictions, all right? So a best-selling book in the year 1999 was a book called “Dow 36,000,” you know, at a time when the Dow was 11,000. So this was an extreme prediction. It was a prediction that the stock market was going to more than triple in value.

If you see those…even three of those four things, all right? Investing or trading being topic A, people quitting good jobs, getting vehemence in response to skepticism, or you start seeing a lot of extreme predictions, that, to me, is the danger signal, and we really don’t see any of those things right now.

Now, that doesn’t mean that the stock market can’t fall 50% in the next year and a half, because it can do that for no reason at all, but I’m not terribly worried by valuations, aside from that I always think it’s a good idea to change your allocation, a little tiny bit, in response to large changes in valuation.

So we’ve seen, for example, the CAPE, the Shiller CAPE, going from about 15 or 25 years ago, up to 30. And if you don’t wanna sell all your stocks right now, but maybe if your allocation back then was 60/40, maybe now it should be 55/45.

Meb: There’s a great phrase that…we had Rob Arnott on and he referred to that concept as ‘over rebalancing.’ So when you get into areas where valuation may be…or sentiment may be particularly extreme, that instead of rebalancing, like you said, to 60/40, maybe it’s to 70/30, etc. Now I love that phrase, I’d never heard it before.

And by the way, Bill’s recommendation for a book for this hurdle was “Common Sense on Mutual Funds,” by Bogle himself, which is a classic. And in this, you know, we started to touch on a handful of the topics in the third hurdle, so we can just segue right into that, which is a close cousin to hurdle two.

Hurdle three is, “Learning the basics of financial market history,” and for the listeners who haven’t spent much time here, this is probably my favorite area to go back and read all these books on historical markets, and Bill’s actually written a couple.

So two quick questions. So one, you already kinda answered, which is, which bubbles are you seeing in the markets right now? And I’m of the same opinion you are, which you’re not seeing a lot of the sentiment extremes, other than maybe in cryptocurrencies and Canadian real estate, I don’t know.

But as you look at the current market now, so what history does it seem to most resemble, if there’s such a thing? And then also, any other takeaways from studying history, that you think are particularly important today?

William: You know, I’m not sure that there’s really any correlate, historical correlate, to the markets of today because what’s characteristic, or what was characteristic of the market, I would say, until about a year or two ago, was that everything seemed to be overvalued.

Certainly three years ago, everything seemed to be almost equally overvalued. Stocks, bonds, foreign stocks, emerging markets, everything. And what has happened with the European financial crisis and also the turbulence we’ve had over the past year or two, in emerging markets, is there’s been a bit of bifurcation.

And so it looks about, I would say, if you were to ask me to give you a precise analogy, we’re about halfway between where we were in, say, 2013 or ’14, when everything was pretty much equally expensive, and where we were in the year 2000, when U.S. stocks, large U.S. stocks were ridiculously expensive, and everything else was fairly valued, if not cheap, because everybody had piled into the tech stocks.

I do think there are higher expected returns in emerging market stocks and in developed non-U.S. markets, and I see the U.S. as being fairly…more than richly valued. So, how do you respond to that? Well, if you had…if one-third of your stock portfolio was foreign 4 or 5 years ago, maybe now it should be 35% or 40%, you know, by selling…You have to sell stocks, sell the U.S. stocks, and when you have to buy stocks, buy the foreign stocks.

Meb: Well, preaching to the choir. And in the two book recommendations, which by the way, we’ll link to in the show notes, are “Devil Take the Hindmost,” as well as one of my favorites that I’ve read recently, is called “The Great Depression: A Diary,” by Benjamin Roth. Which is a really useful look back to, I believe he was a lawyer during the Depression who just kinda kept a diary that is just so illuminating, at a time when most investors trying to realize what is historically possible, in a time when stocks dropped 80% to 90%. And so thinking that however, maybe, remote, that that is a possibility. And I’m gonna add my favorite, by the way, for this chapter, which would be “Triumph of the Optimists,” which was written by a handful of British professors.

William: Let me interject a couple of comments, and I…you threw me some red meat and I can’t…

Meb: Good.

William: …help but pick up on them. The Roth book is a fabulous book, and there’s a wonderful section in there that I love to quote, where people understood, it’s quite clear from the diary, from his diary, that people understood that stocks and bonds were cheap, okay? And everybody knew they could…most everybody knew they were going to make high returns, but no one had any money.

Ghere’s a wonderful correlate of that, a quote from Benjamin Graham, and I can’t remember whether it’s from “Intelligent Investor” or “Security Analysis.” I think it’s from “The Intelligent Investor.” In which he said, “That the people with the cash didn’t have the enterprise, and the people with the enterprise didn’t have the cash.”

And what he meant by the word ‘enterprise’ was moxie, was guts. Plunging, putting money into the market. So the ones who had already plunged into the market, the plungers, the ones with the enterprise, had no money left. Whereas, the ones who didn’t have any enterprise and who weren’t ever going to buy stocks, those were the ones with the cash.

The other thing about “Triumph of the Optimists” is…you know, and Elroy Dimson, and Staunton and Marsh, they’re wonderful guys and it’s a wonderful book, but it costs $150, and you can get pretty much the same thing, as well as a lot of additional research, from a series of free yearbooks that they put out with Credit Suisse.

So just put in ‘Triumph of the Optimists, Credit Suisse, Elroy Dimson’ into your search engine, and you’ll come up with about 9 or 10 now, white papers that are free, and basically contain everything in “Triumph of the Optimists.” plus a lot more.

Meb: That’s my number one read of the year every time it comes out, and it’s definitely not for the beginner reader, but there’s so much in there. That’s like a master’s of investing right there. Well, so, come into the next one, which is hurdle four. It is particularly interesting to me. We’ve got a former biotech engineer here, and then also a doctor. And this one is…the hurdle is “Know thyself,” and basically overcoming the biggest enemy, which is yourself, when implementing your portfolio.

So why is it so hard? And is there any sort of hacks you have that you think are useful for investors becoming, not their own worst enemy? And is it something that investors can do to grow that muscle, of becoming not a detriment to their portfolio, or is it something they just have to learn the lessons the hard way? What’s your thoughts here?

William: I’m afraid that the answer is your last answer, which is, you just have to learn the hard way. One of the things I’m fond of saying is that the most profitable purchases I’ve made, in my life of securities, were made at the time when I feel…felt like I was about to throw up.

The more comfortable you are buying something in general, the worst an investment it’s going to be. If you feel sick at your stomach when you’re buying something because it’s been doing so poorly and you just see decreasing in price every day — that, in the long-term, is generally going to wind up to be a good investment. You know, a lot of the Kahneman/Tversky stuff is also extremely valuable, and particularly to realize just how overconfident people can be.

And knowing yourself is really hard because, we, as human beings, have this tendency towards self-affirmation, we always wanna feel good about ourselves, so we become overconfident. And there is the old chestnut about 90% of drivers thinking they are better than average, but there’s something else that I think is even more important than that, and that’s called the Dunning-Kruger Effect, which basically says that there is an inverse correlation between competence and self-evaluate competence.

So the people who tend to be the best at something tend to be consumed by self-doubt, whereas the people who are absolutely incompetent turn out to be very, very self-confident.

They think they’re really doing very well, and the reasons for that are very, very complex. But you see it in a number of fields you certainly see it in medicine. The best doctors tend to be consumed by self-doubt, the real quacks turn to be supremely self-confident. And it’s the same way in investing as well. So if you think you’re a really good investor, that is a dangerous sign.

Meb: And it’s interesting because I certainly have most of these behavioral biases. I’m overconfident, I take too much risk — which is one of the main reasons I became a quant. But it was also, just like you described is, I was through that experience after losing a bunch of money, and blowing up my account, and doing all the dumb stuff, and it’s kind of like, you know, telling an investor, “Hey, here’s what it’s going to feel like to lose 50%,” or whatever your portfolio.

You know, the analogy being it’s like explaining sex to a virgin, where you…it’s really hard to try to tell people what the real physical pain of losing money is like, until they’re eating mustard sandwiches for a year. Is there one behavioral bias, that you think is the most destructive, that is the one you see the most from investors?

William: Yeah, it’s overestimating your risk tolerance. It’s just exactly what you described. There’s that wonderful phrase…paraphrase that you just paraphrased, which comes from Fred Schwed, “Where Are the Customers’ Yachts?” And I can’t do — quote word-for-word but I can get close, which is that, “No picture that I can draw, or no words that I can write down can describe what it feels like to lose a real chunk of money that you used to own.” And that’s exactly it, is you can spreadsheet…you know, if you’re a quant you can spreadsheet out things from now until breakfast. You can show your portfolio falling 30%, or 40%, or 50%, or 60%, depending on what your portfolio is, and you can look at it and say, “Yeah, I’ll be able to tolerate that.” And then when it happens in real-time, that you’re faced with a completely different kettle of fish, it’s not nearly…It’s 100 times worse than you thought it was going to be.

Meb: There’s a quote that I’m going to read from Bill that I’ve certainly used many times, and I’ll summarize it real quick, it says, he was talking about 2008 crisis, and he said, “A lot of people won the game before the crisis happened. They had saved enough for retirement, but continued to take risk by investing in equities. Afterward, after the crisis, many of them sold either at or near the bottom, and never bought back in, and those people irretrievably damaged themselves.

“I began to understand this point 10, 15 years ago, but now I’m convinced, when you’ve won the game, why keep playing it? How risky stocks are to a given investor depends on which part of the lifecycle he or she is in. For a younger investor, stocks aren’t as risky as they seem, for the middle-aged, they’re pretty risky, and for a retired person, they can be nuclear level toxic.”

And so, I think this is a really useful description of portfolio construction, and we often tell people to err on the side of less risk than more. And I don’t even really have a question there, I just wanted to read your wonderful, wonderful quote, but I think it’s a really useful illustration.

William: Yeah, people over-interpret that by…That passage you just read is saying that old people or older people shouldn’t own stocks. And that’s really not what I’m saying. What I’m saying is, the money that you need to retire on, the money that you need to subsist safely on, during your retirement, should be very conservatively invested.

Now, if you’ve got three or four times that amount of money, you can invest the surplus in stocks, if you can tolerate it. Because it’s really not your money, okay? That money is going to somebody else. It’s going to go to your heirs or your charities, or, if you’re patriotic enough, it’s going to go to Uncle Sam.

Meb: And that you illustrated a pretty important point with a lot of the online risk-tolerance questionnaires is they automatically assume, and not too terribly so, that young people should be having most their allocations stocks, and older people, most in bonds. And generally that’s probably a good rule of thumb, but in many cases the opposite could be true.

The book recommendation for this section, for this hurdle was “Your Money and Your Brain,” by Jason Zweig. A lot of great behavioral research books out there, this is certainly one of the best.

All right, so you’ve got the equation for the portfolio, you learn to pay down your debt and not spend too much money, you’re saving, you do a little bit of understanding finance and history.

The fifth hurdle coming to is kind of the implementation, and one of the big things you say is, “Avoid the monsters,” which is really the predatory financial pros. And you said this in a very nice way, you said, “You’re in fact locked in a financial life and death struggle with the investment industry. Losing that battle puts you at increased risk of running short of assets far sooner than you’d like.” What’s your comments and recommendations here?

William: Well, it’s funny. I mean, this came home to me today. I was setting up an online banking account with a large financial institution that also has a brokerage on, and I was on hold for a few minutes, it wasn’t too bad, but the whole soundtrack was financial commentary, and it’s all, what you and I would call, financial pornography. That was a term was invented by…Oh, trying to remember the name.

She wrote an article in the “Columbia Journal.” Jane Bryant Quinn, it’s her phrase. And so it’s all about where this particular company thinks that interest rates are going to go, and where the economy is gonna be wanting [SP] to go, and what stocks you should buy, and what stocks you should sell — and it’s snake oil.

And the large, full-service brokerage houses and financial services institutions want to convince you that they know how to pick stocks, and they know how to time the market, and they can interpret what’s happening in real-time in the economy and how it affects your portfolio. Which is, it’s an impossibility. Anyone who knows anything about finance knows you can’t do that because of market efficiency.

And you need to stay away from these people. Just stay away from them. Don’t listen to them, don’t give them your money to invest. You should invest only in vehicles that are passive and that have the lowest possible fees. And of course, you and I are both very fond of The Vanguard Group, but there are other places where you can invest just as cheaply as well.

Meb: And so, but here’s kind of the challenge for a lot of people, right? As they say, “Avoid a lot of the predators,” and there’s a lot of good ones out there. So one, for a lot of people, it’s how to find them, but two, some people say, “Look, I can do it on my own. I’ve conquered all these roadblocks.” But I read in a few places where your estimates of people that could probably do it on their own…Like, I’ve seen some place where you say it’s as low as 1%.

So there becomes this challenge for people that either they think they can do it on their own, and they can’t, because they fall prey to all the other hurdles. What’s, kind of, your recommendation for most of the individuals that would be listening to this podcast? Is it to pair up with an advisor? Is it to really try to do it on their own? What’s your best takeaways?

William: The best way to do it, is simply to make it as simple and as automatic as possible. Now I have the three-fund portfolio that I recommend, but if you have this option, even better than that is a good lifecycle fund, a target retirement fund. So if you have one of those funds, it has very low expenses. Vanguard, if you were lucky enough to have the Vanguard Target Retirement funds, or even better, if you’re a federal employee and you had access to the TSP lifecycle funds, just put your 15% of your salary, 20% of your salary into that every month, and don’t ever look at your brokerage statement, don’t ever look at your financial statement. That’s the way to do it.

If you can do it on your own and you can maintain a more complex portfolio than that, you know, a three-fund portfolio or something more complex than that, at a bare minimum it requires an ability to spreadsheet and to keep track of your investments.

And once you’re keeping track of your investments, you’re already going to possibly get into trouble, because one of my favorite phrases, and maybe it comes from you, maybe it comes from someone else. I can’t remember who it comes from, that an asset allocation is like a wet bar of soap, the more frequently you touch it, the more rapidly it disappears.

And so, yeah, you can do it yourself, but it’s difficult, and I think the 1% estimate is probably about right. I come up with actually a theoretical estimate of around one one-hundredth of 1%, but that may be off.

Meb: And so what do you think about all the technological advances, like a lot of the robo advisors today? Do you think that’s interesting, not that interesting, more of the same? Any thoughts there?

William: Well, you know, robo, in general I think the robos are a good idea. Their expenses are low and they’re done automatically, and if you can do it and if it enables you to do it in a hands-off manner, that’s all to the good. But you’re just as well-off, if not better off, with a good life strategy fund, which does exactly the same thing as a robo.

Meb: You know, Jeff and I, and then the crew here at Cambria, we brainstorm a lot of behavioral nudges. We’re just trying to get people to do the right thing. And we’ve mentioned a lot in this podcast already, such as having automatic savings plan to go into your 401(k) and all these other things to do.

The challenge we’ve always thought about, as we said, for example, we have an asset allocation ETF that charges, all-in, 25 basis points. But the problem is with any fund or ETF, people can still sell at any given day. And same thing, even if you have an advisor, if you put in that wall in between you and your worst version of yourself, you can still fire that advisor, and many people do after a few years of underperformance or whatnot.

So Jeff and I and the crew were brainstorming a strategy, he said, “What if you could do a mutual fund, that was very low-cost,” so less than 50 basis points, asset allocation, global fund, “and let’s implement both penalties and rewards.” So the penalty would be a trailing redemption fee over maybe 5 or 10 years. So maybe year 1 it’s a 5% fee or 10%, or something really terrible, and then trails the, whatever, 5 or 10 years to where it’s 0, so if you hold long enough it’s no fee.

But the reward is that the fee collectively goes back to the investors, where you get not only the benefit of holding for a long period, but you benefit off other people. I think it’s a great idea, but I think we’d end up getting sued at some point anyway. Anyway, throwing it out there. So if you come up with any great behavioral nudges, let us know, we’d love to…

William: I thought…

Meb: …implement…

William: …about that precise strategy myself, I think it’s a great idea, and I think the lawyers…you’re right, the lawyers would eat you alive.

Meb: I was talking to a common friend, Jason Zweig, about it, and he said, “Meb, there was something similar existed in the ’90s, where it had, like, a longer-term lockup.” And sure enough, in 2000, all the lawyer calls started coming and suing the fund for redemption.

So anyway, on the to-do list, no reading lessons for this chapter, but in the summary we’ve got two more. One was, “How a Second Grader Beats Wall Street,” by Allan Roth, which I don’t think I’ve ever read, and “All About Asset Allocation,” by Rick Ferri, who is somewhere traveling the U.S. in a RV right now, I think.

So that kinda winds up the summary of the book. I would like to turn this to a little more kind of potpourri questions on all sorts of different topics, and we don’t have too much time, sadly, so I’m going to try to have these be quick hits.

One interesting development we saw in the last couple of weeks, “The New York Times” was reporting on it, was that the CIO of Wealthfront, Burt Malkiel, investment legend, has written one of the most famous books, “A Random Walk Down Wall Street.” Had made a little bit of an interesting announcement, to where he has kind of changed his colors a little bit, to now being a proponent of smart beta investing.

Rob Arnott called that a fascinating turn of events. I wanted to hear your thoughts in general on moving away from the market-cap weighted indices. Something you like, love, hate, agnostic?

William: You know, smart beta is…it’s a marketing term. A better term is smart marketing. There’s nothing wrong with it, I’ve written about the same basic concept in all of my books, except for the last one that we’re talking about, which is “If You Can,” but my more in-depth books talk about this basic idea, which is a tilting towards small stocks, and particularly value stocks. And that’s what smart beta does.

Smart beta underweights, or completely eliminates in some cases, the more expensive stocks and loads up on cheap stocks by quantitative criteria. You know, you’re talking about smart beta, I don’t know, it’s a terrible analogy. It’s like talking about pizza. There is lots of different kinds of pizza and there’s lots of different kinds of smart beta.

So the two big shops that do it are Rob’s, which is why he uses the word “fascinating.” His products are certainly very well-constructed. And then the other shop that does it, of course as we’re both aware, is Dimensional Fund Advisors. There’s almost no difference between what Rob’s doing and what DFA is doing. You’re going to get higher returns — probably — and that will be for higher risk, all right?

So if you look, for example, what DFA’s funds did during the financial crisis, they got hammered worse than the market did, but their long-term returns are higher, and that’s just the way things should be in finance.

And the problem that I see with smart beta, because it’s being met by a wall of dumb money, the people who really have no concept that this approach is going to have periods of underperformance, where it’ll underperform the market overall. And when that happens they won’t understand what’s happening. They will bail, prices will fall even lower, which will raise long-term returns for people who got discipline and actually understand the strategy.

Meb: So what other areas are you excited about today? Anything in particular you’re thinking about? Research? You mentioned bubbles a little bit. Any other areas of investing and finance that you’re particularly keen on? You know, looking out in the next coming years?

William: I mean, I hate to be a curmudgeon. If you’re a doctor or a lawyer, you have to read tens of thousands of articles or of case studies, case law. In finance, if I had to make a list of the seminal articles in finance that everyone really should understand, it wouldn’t be more than 30 or 40 articles long, so the odds of…

Meb: I would love to see that list, I think that’s perfect homework for you. We’ll publish it if you put it together.

William: You know, it’s really not that hard. All you would have to do is just go into JSTOR, and for “Journal of Finance” and JFBN [SP], and a few other high-level journals, and just look at the ones that are the most cited. You get the same list as I think I would produce.

Obviously you’d start with Fama and French and you’d talk about the Limits of Arbitrage by Lakonishok and Shleifer, and then it goes down from there, of course starting with Michael Jensen’s seminal article in 1964 on fund performance. So the bottom line is, I don’t get very excited about very many things in finance at all because I don’t find…the research is interesting to read, but I don’t find it of much practical import.

Meb: One or two more questions, and then we’re going to have to wind down and let you go. This next question, or just jumping-off point, I think is an area that many, many, many, particularly individuals, get wrong or misunderstand. And you say, “Only an income-producing possession, such as a stock, bond or working piece of real estate, is a true investment. Homeownership is not an investment. It’s exactly the opposite — a consumption item.” Maybe explain what you mean there.

William: Yeah, you have to own a home, all right? Or if you don’t own a home, you have to pay rent to someone. And so in effect, your house is paying you in [inaudible 00:47:41] rent, which really isn’t income. To me, counting your house as an asset makes almost as much sense as counting your food budget. Obviously you can’t sell your food and you can sell your house, but if you sell your house, then you’ve got a real problem, which is, then you gotta find…you’ve gotta pay rent to someone.

And a house, in general, I mean, of course there are exceptions, and there have been exceptions, which are some of the richer real estate markets. But on average, a house is a terrible investment, because its real value doesn’t increase by much more than about 1% per year after inflation.

And you’ve got expenses, you have maintenance, you have upkeep, you have taxes to pay, so it’s really not a great investment. It’s an expense, and the less you can spend on your house, probably the better off you are.

Meb: I think that’s something that almost always surprises most of the individual investors I talk to. Two more quick ones, and we’re going to let you go. Cryptocurrencies, Bitcoin. Any feelings? Any thoughts? Rat poison, like Charlie Munger says, or a major new innovation?

William: Well, you know, it’s both. From the point of view of an asset class, sure, it’s rat poison. But I think it’s interesting as a financial technology, which the whole Blockchain concept may change the entire nature of how our financial system works. But that doesn’t mean it’s a good investment.

The analogy I guess I would use would be the internet companies of the ’90s. The internet really did change the way we live, it really did change everything, but on average you didn’t make any money by investing in these companies.

Meb: One more question, and this is the one that we ask everyone on the podcast. In 2017, which is, and you can take a minute to think about it, if you want. Looking back over your career — and this could be good, bad, money-losing, money-winning, whatever. What is your most memorable investment or trade?

William: Oh. Well, I was hoping you were going to ask me what’s the biggest mistake I made? That’s what did [inaudible 00:49:57].

Meb: Hey, that’s the same one. For me, it’s the same exact one, frankly.

William: Yeah. You know, when I was much younger I did all the stupid things that young, stupid professionals do, which is, I dabbled in futures, I picked individual stocks and mutual funds, and that turned out about as well as you might expect those things to turn out. But, the biggest mistake that I made, easily, was not understanding…and I only understood this, really understood this well the past five years, is the difference — is how the risk of stocks varies over a lifecycle, so I should have been much more aggressive in my stock purchases and my allocation when I was a much younger man. And that’s easily the biggest mistake I made.

Because I didn’t understand that stocks, to someone who’s saving a lot of money and whose investment capital is dwarfed by their human capital. Which was the situation when I was in my 20s and 30s, and even early 50s, stocks aren’t all that risky and I should have been much more aggressive.

Meb: Yeah, I mean, listeners have already heard about all mine, which are many, and the interesting part is I always say, “Look, I’m glad they happened, particularly when I had less money,” but mine was certainly an option string, along [SP] with biotech stocks back in the day. You had mentioned earlier, and I don’t know if you wanna expand on this or…because we’re running out of time, a bit about…you know, we like to ask people how their thinking has changed on certain topics, and you briefly mentioned how your thinking on bubbles has changed, and why theorists are so confused by them. Is that something you wanna chat for a minute about, or we gotta let you go?

William: Well I think I pretty well-covered it, which is that I think that when you talk about bubbles, the analogy I like to use, I didn’t talk about this but it’s a wonderful analogy, is the way Potter Stewart, Justice Potter Stewart thought about pornography, okay? Which was, he has this long opinion in Jacobellis -v- Ohio, and the thing that everyone remembers is the tagline, which is, “I know it when I see it,” okay?

But the sentence or two that comes before that is, “I really don’t know how to describe it or define it.” And if he were in finance and he was talking about bubbles, what he would say is, “I don’t know how to mathematically model bubbles, but I know it when I see it.” And the trick is to read about the ’90s, read about the real estate…or I think most people don’t even remember what the real estate market looked like 10 years ago, 11 years ago. That’s what a bubble looks like, and we’re not in one now.

Meb: Yeah, I mean, and there are some kind of soft, quantitative resources. We mentioned some of the sentiment surveys by Intelligors Investing [SP] and American Association of Individual Investors, and our favorite example is the AAII study which goes back to the ’80s, the single most bullish month, people were on stocks was in January of 2000, then the single most bearish month they were, was in March of 2009.

So there’s some sort of quantitative guidepost we can use, but I have the all-time secret weapon. Which is my mother, and she gets it right exactly 180 degrees wrong on almost every major bubble, top, peak and bottom. But she’s been very quiet lately. She hasn’t said much, she hasn’t even brought up Bitcoin, so I got…it’s kind of a calm market for her.

William: Yeah. That’s a really useful thing to do, and I think this is a dirty secret that all finance professionals have, is we all have certain people who are…and they’re friends or acquaintances, they’re very often relatives, who we listen to very carefully because they’re always wrong.

Meb: Although the problem is, my mom is the number one podcast listener, so I may have tainted the pool by mentioning it, so she may be biased now.

Bill, this has been a blast. I mean, we may have to get you back on in a year from now to do the super wonk-y version of this podcast with, like, the really deep academic dive. But if people wanna follow you, where is the best place they can find more information?

William: Go to my website, efficientfrontier.com. But I have to tell you, that site is more of a mausoleum than anything else. I mean, I almost never post on it anymore. In fact, I think the last time I posted on was two years. I spend most of my time reading and writing about things that aren’t directly related to finance anymore, but I have this other career as a non-fiction writer, which I spend most of my time on. I mean, I can’t say I’m getting bored with finance, I always find it fascinating, but I’m not writing about it nearly as much as I used to.

Meb: Have you read anything particularly wonderful lately or anything that’s really stuck out for our summer reading list?

William: Oh, dear. Not in terms of investing.

Meb: No, anything. We’re done with investing now.

William: Well, there’s two books, and one is the book that I recommend to every single person I come in…I run into, which is Tetlock’s “Expert Political Judgment.” He’s got a newer one on “Superforecasting,” but the “Expert Political Judgment” is, it will revolutionize the way you look at forecasting and the world, and of people who forecast, and particularly of pundits. It’s a marvelous book. And then the other book was a book written by Walter Scheidel called, “The Great Leveler,” which is about the fundamental nature of economic inequality of capitalism, and it’s a very depressing book. But if you wanna understand what’s happening in the country, politically, that’s a book you should read.

Meb: Excellent. I’ve read Tetlock’s more recent one but haven’t read either of these books, so we’ll toss’em up on the show notes.

William: By the way, by the way, they are not cotton candy, they are not beach reads. They are serious books.

Meb: The book that I’ve given more than anything, other than our own books, is a behavioral psychology book, and the title is a little misleading because it’s about evolution and biology. Have you read Olivia Judson’s “Dr. Tatiana’s Sex Advice to All Creation?”

William: No. What a wonderful title…

Meb: Bill, I’m gonna send it to you as a thank you for coming on the podcast. This is my single favorite book. She’s actually coming out with a new book later this year, I think, because we’re trying our best to get her on the podcast. But it’s this wonderful deep dive into all sorts of different species on the planet and how they’ve, kind of, evolved, all these crazy traits to each other. And it really was one of the first books for me that, you know, give you a step back and kinda, made you think of why you spend all the time doing what you do all day, may not necessarily be…it may be stuck in your genes somewhere. Really fun book. Readers, it’s well worth the time.

Bill, it’s been awesome, I’ve had a blast. Thanks for taking the time today.

William: Me too, you have a good one.

Meb: Listeners, we always welcome feedback and questions for the mailbag at feedback@themebfabershow.com. We’ll post a lot of show notes, links to Bill’s books, his website, everything else at mebfaber.com/podcast.

You can always subscribe to the show on iTunes, and if you’re enjoying the show, please leave us a review. Thanks for listening, friends, and good investing.

Sponsor: Today’s podcast is sponsored by the ride-sharing app Lyft. While I only live about two miles from work, my favorite means of getting around traffic-clogged Los Angeles is to use the various ridesharing apps, and Lyft is my favorite. Today, if you go to lyft.com/invite/meb, you get a free $50 credit to your first rides. Again, that’s lyft.com/invite/meb.

[00:58:00]

[music]

[00:58:20]