Episode #107: James Montier, GMO, “There Really Is A Serious Challenge to Try to Put Together an Investment Portfolio That’s Going to Generate Half-Decent Returns On A Forward-Looking Basis”

Guest: James Montier is a member of GMO’s Asset Allocation team. Prior to joining GMO in 2009, he was co-head of Global Strategy at Société Générale. He is the author of several books including “Behavioural Investing: A Practitioner’s Guide to Applying Behavioural Finance”; “Value Investing: Tools and Techniques for Intelligent Investment”; and “The Little Book of Behavioural Investing”.

Date Recorded: 5/22/18 | Run-Time: 59:14

Episode Sponsor: Inspirato – Experience the world’s most exclusive vacation homes, all managed, staffed, and maintained by Inspirato. As a Meb Faber listener, you will receive a credit of $1,000 towards your first vacation when you join Inspirato.

Comments or suggestions? Email us Feedback@TheMebFaberShow.com or call us to leave a voicemail at 323 834 9159

Interested in sponsoring an episode? Email Jeff at jr@cambriainvestments.com

Summary: The chat starts on the topic of James’ questionable sartorial choices. He tells us he’s “always been a fan of dressing badly.” But the guys quickly jump in with Meb noting how James has generally been seeing the world as expensive over the last few years. Has anything changed today?

James tells us no; by in large, we’re still trapped in this world where, frankly, you’re reduced to this game of “picking the tallest dwarf.” In general, every asset is expensive compared to normal. He summarizes, telling us “there really is a serious challenge to try to put together an investment portfolio that’s going to generate half-decent returns on a forward-looking basis.”

Meb digs into, focusing on James’ framework for thinking about valuation, specifically, as a process. James starts from accounting identities. There are essentially four ways you get paid for owning an equity: a change in valuation, a change in profitability, some growth, and some yield. James fleshes out the details for us, discussing time-horizons of these identities. One of the takeaways is that we’re looking at pretty miserable returns for U.S. equities.

James notes that we now have the second highest CAPE reading ever. Or you could look at the median price of the average stock – the price-to-sales ratio has never been higher. Overall, the point is to look at many valuation metrics and triangulate, so to speak. When you do, they’re all pretty much saying the same thing. James finishes by telling us that from his perspective, U.S. equities appear obscenely expensive.

Meb takes the counter position, asking if there’s any good argument for this elevated market. Is there any explanation that would justify the high values and continued investment?

James spends much time performing this exact exercise, looking for holes. He tells us that most people point toward “low interest rates” as a reason why this valuation is justified. But James takes issue with this. From a dividend discount model perspective, James doesn’t think the discount rate and the growth rate are independent. He suggests growth will be lower along with lower rates. He goes on to discuss various permutations of PE and other models, noting that there’s no historical relationship between the Shiller PE and interest rates.

Meb comments how so many famous investors echo “low rates allow valuations to be high.” But this wasn’t the case in Japan. Meb then steers the conversation toward advisors who agree that U.S. stocks are expensive yet remain invested. Why?

What follows is a great discussion about what James calls the “Cynical Bubble.” People know they shouldn’t be investing because U.S. stocks are expensive, but investors feel they must invest. If you believe you can stay in this market and sell out before it turns, you’re playing the greater fool game. James tells us about a game involving expectations – it’s a fun part of the show you’ll want to listen to, with the takeaway being how hard it is to be one step ahead of everyone else.

The conversation bounces around a bit before Meb steers it toward how we respond to this challenging market. What’s the answer?

James tells us there are really four options, yet not all have equal merit:

1) Concentrate. In essence, you own the market about which you’re most optimistic. For him, that would be emerging market value stocks. Of course, buying and holding here will be hard to do.

2) Use leverage. Just lever up the portfolio to reach your target return. The problem here is this is incompatible with a valuation-based approach. Using leverage implies you know something about the path that the asset will take back to fair value – yet it may not go that route. You may end up needing very deep pockets – perhaps deeper than you have.

3) Seek alternatives like private equity and private debt. The problem here is most are not genuinely alternative. They’re not uncorrelated sources of return. James tell us that alternatives are actually just different ways of owning standard risk.

4) The last option is James’ preferred choice. Quoting Winnie the Pooh: “Never underestimate the power of doing nothing.”

Next, Meb brings up “process” as James has written much about it. James tells us that process is key. Professional athletes don’t focus on winning – they focus on process, which is the only thing they can control. This is a great part of the interview which delves into process details, behavioral biases, how to challenge your own views, and far more. James concludes saying “Process is vitally important because it’s the one thing an investor can control, and really help them admit that their own worst enemy might be themselves.”

There’s plenty more in this great episode: James’s answer to whether we’re in a bubble, and if so, what type… market myths that people get wrong involving government debt… and of course, James’ most memorable trade. This one was a loser that got halved…then halved again…then again…then again…

How did James get it so wrong?

Links from the Episode:

- 2:20 – What changed for James around 2016, in particular with his wardrobe

- 3:48 – John’s view on the markets today

- 5:03 – Framework for thinking about valuation

- 8:40 – Is there a scenario where the current high valuations for stocks is not so bad?

- 13:44 – Why so many own US equities despite thinking/knowing they are expensive

- 16:45 – Number guessing game

- 19:55 – Risk for the drawdown

- 20:34 – Risk/volatility chart

- 24:22 – Graphic from Star Capital about the more you pay the higher the chance of a loss

- 24:47 – Sponsor: Inspirato

- 26:01 – What’s a trader to do given the concerns over the valuation of US stocks

- 36:10 – How to develop a good process for investing

- 36:28 – The Little Book of Behavioral Investing: How not to be your own worst enemy – Montier

- 39:37 – Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think – Wansink

- 46:04 – James’ view on bubbles

- 48:50 – Views on debt

- 55:11 – Most memorable investment

- 58:31 – Where to follow James – the GMO website

- James’ behavioral tests: here and here

Transcript of Episode 107:

Welcome Message: Welcome to The Meb Faber Show where the focus is on helping you grow and preserve your wealth. Join us as we discuss the craft of investing and uncover new and profitable ideas all to help you grow wealthier and wiser. Better investing starts here.

Disclaimer: Meb Faber is the co-founder and Chief Investment Officer at Cambria Investment Management. Due to industry regulations, he will not discuss any of Cambria’s funds on this podcast. All opinions expressed by podcast participants are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of Cambria Investment Management or its affiliates. For more information, visit cambriainvestments.com.

Sponsor: Today’s episode is brought to you by Inspirato, provider of the world’s most exclusive vacation homes. I just joined Inspirato and I can tell you, they go way beyond a typical vacation rental. It’s all the best parts of vacation house, the space, the privacy, the kitchen and dining room combined with the service you’d expect from a five-star hotel. That means premium linens and furnishings plus daily housekeeping and onsite concierge and much more. It really is the best of both worlds. From Turks and Caicos to Tuscany, you’ll find consistent luxury. Right now, our listeners can receive right $1,000 towards their first trip to one of their exclusive vacation homes and they become an Inspirato member. You can call 310-773-9474 and mention Meb Faber or visit inspirato.com/mebsentme to learn more. That’s inspirato.com/mebsentme.

Meb: Welcome podcast listeners. Today’s show is going to be a fantastic one. Our guest comes to us from one of the most respected shops on the street, GMO, where he’s a member of the asset allocation team. Prior to joining GMO, he was co-head of global strategy at Soc Gen. Also a prolific writer. He’s written a handful of leather-bound books, a slew of papers. We’re so happy to have him today. Welcome, James Montier.

James: Thank you very much, Meb. Thank you for having me.

Meb: So, James, in prep for this chat, I went and re-read almost every paper I could find of yours, going back…

James: You have my sympathies for a start.

Meb: Almost 20 years and scanned your books because one of them is 700 pages, but I’d read them before. But I noticed there was a very kind of sharp break in around 2016 when you went from your photo was a kind of a very drab, wearing a dark shirt to, all of a sudden, wearing Hawaiian shirts. Was that because your market outlook in 2016 became so much rosier where you said, “You know what, I think the markets, this is… the time to be fully invested”? Was that kind of why you changed the photo or…?

James: Oh, if only that were the case, it would have been a lovely one, but, no. Yeah, I always been a fan of dressing badly throughout my career. And I guess I joined GMO in 2009 and when I joined, one of the things that the company was excited and nervous of was the fact that I was usually very badly dressed and they decided that I should start to dress a little better if I was gonna be here. I have quite such outlandish views on the world I preferred if I looked stayed, and I think over the intervening time they’ve got used to me and I’ve got used to them and I eventually decided I could return to showing my true colours and hence the return to truly outrageous shirts, and even today I’m wearing yet another really quite hideous floral design just to prove my ever-expanding wardrobe of tasteless shirts. It’s still there. So, no, it’s sadly unrelated to any views on the market and much more to do with both GMO and I growing together.

Meb: Well, you’d fit right in in our Los Angeles office. Style advisory is equally as casual. So let’s dive right in. You have had a market view over the past few years where you’ve kind of taken a look around and you said, “Part of the problem from our perspective when you look at the world’s assets is nothing is cheap.” So, let’s get the depressing stuff out of the way early. What’s kind of your market view? Was it the same as it was over the past few years? How do you kind of view markets today?

James: Yeah, very similarly. I think that things do change, obviously, but by and large we’re still trapped in this world where, frankly, you’re reduced to playing a game of picking the tallest dwarf, not a politically correct game, but the one I think we’re forced to play at the moment, where you’re essentially looking at pretty much almost every asset being expensive compared to kind of what we would think of as normal. And that makes asset allocation a real challenge because too much of history what we’ve seen is periods when, let’s say, if risk assets equities and the likes were expensive, you could usually sit quite nicely in cash and say base and assets like bombs and just sit on the side lines and wait. But what we’ve seen in the last few years is this kind of much broader degree of overvaluation that there really is, I think, a serious challenge for trying to put together an investment portfolio that’s gonna generate kind of half decent returns on a forward-looking basis.

Meb: And so let’s talk specifically with everyone’s favourite investment, U.S. stocks. And you guys do so much work on valuation. And we’ve certainly talked a lot about it here on the podcast before and I think it’s something that people really struggle with. And maybe talk a little bit just kind of briefly on what you think your framework for thinking about valuation is. And any particular favourite ways to think about it as a process as well.

James: Sure. So, that’s an excellent question. The way we tend to look at it is to start from accounting identities, and the nice thing about accounting identities is they have to be true. So, if you’re thinking about an equity or an equity market, you can essentially say, “Look, there are four ways you get paid for owning an equity. You could get a change in valuation, a change in profitability. You’ll get some growth and some yield. Now, expose, I can always decompose your returns into those component elements, and when you do that, what you see is in the very long term that it is all the growth and yield that gives you your equity and return. In the short term, it is always the P and margin, so they’re kind of cyclical adjusted a bit of the valuation if you like that generates all the volatility.

So, to take that from an accounting framework into a kind of forecasting framework, you obviously have to say something about where you think those variables are going to go. What we do is say, “Over the course of the next seven years, things should return to normal.” And we can talk a little more about what normal is if you like, but perhaps you can think of it as, at least in very rough terms is kind of returning to a long period average. It’s not quite the way we think, but it’s a good approximation. So, what you do is, you say, “Okay, PEs today are pretty high.” They’re coming back to normal margins, profitability pretty high, that should come back to normal you’ll get in your growth. When you do that, what you get is pretty miserable outlook for the U.S. equities.

Now, now you can get very similar results from a pretty wide measure of evaluation measures. So you don’t have to use that kind of decomposition based framework. You can look at something like Shiller PE. The Shiller PE, as you well know, we are now the second most expensive we’ve ever seen. We have now surpassed 1,929, we’re now second with only 2,999. Strangely enough, you don’t hear too many balls going out and saying, “Go and buy U.S. equities because it’s just like 1999.” They kind of worked out. It wouldn’t be the world’s best sales pitch. But that is the reality of where we are for valuation perspectives. You could look at things like approaching the median stock, you don’t want to look at the market cap average, you could just look at the average stock. You get a very similar picture if you’re looking at something like the average stock’s price sales, it’s multiple. It has never been higher.

And the point is that these various different valuation measures is really to help you triangulate. If it was just one particular indicator that was kind of giving you a signal, you guys want to have a lot of faith in that particular signal, or you’d be saying, “Okay, well, look, it’s just one.” But when you look at a wide range of valuation-based metrics and they are all pretty much telling you the same thing, then you could have more certainty in your view. From our perspective, pretty much every measure, we look at shows U.S. equities to be. What I’ve often described as seemingly expensive. So, on the baseline of all forecast going back to normal, you end up with a forecast that’s something like -3% to -4% per annum for the next seven years after inflation. So, it’s in real terms, which is a pretty damn depressing kind of outlook to have.

Meb: So, you mentioned, it’s funny. You say, “Pretty much every valuation metric.” But we’ve written on Twitter about this and on the podcast and say, “Can someone please find me any valuation metric that says stocks are cheap?” And I’ve yet to find one. But you’ve talked a lot a bit about this in your writing. You know, your early part of your career was mentioning so much research on behavioural investing. And to your credit, one of the things you often talked about, it says, “Look, so many analysts and portfolio managers and people and life, in general, have spent so much time just confirming their views.” And so let’s maybe take the flip side. Is there a good argument for… We’re looking around and we see everything is expensive. Is there an argument where either that’s okay or this works out in a way or Elon Musk finds a new element on the moon that gives us free energy? I mean, what’s the scenario? If someone was to break down your argument, is there any valid points that you think, “Okay, maybe this is a possibility that this may not be so bad”?

James: I think that we spend a long time trying to engage in exactly that activity So it’s one of my primary jobs here is kind of to play devil’s advocate and pull on the strings. And I’ve spent a huge amount of time over the last two years trying to find a decent explanation as to why this time is different, if you will, those terrible words. But, in general, I haven’t been able to construct one, right? Every argument I have come across I just find that some sort of logical flaw in it. So probably the most common one is low-interest rates. Low-interest rates justify high equity evaluations. The problem with that is if you think about it from just a simple dividend discount model perspective, if you think about it, your top line of your dividend discount going out in the future is cash flows you expect to receive. The bottom line is discount rate that you’re using.

Now, there’s a reasonable argument I think we made that the discount rate that you use can actually be independent of the interest rate, but let’s assume it isn’t, let’s assume it is a function of the interest rate. Therefore, the interest rate drops are discounting those cash flows by a lower discount rate, therefore you should end up with a higher valuation. The problem I have with that argument is, I don’t think the discount rate and the growth rate are terribly independent, so those cash flows going out across the future are gonna be lower because growth is lower. And the reason the discount rate is lower, it’s also because growth is lower, i.e., low rates because growth is weak. What you actually end up with is an unchanged valuation, right? You end up with lower returns going forward for sure, but you don’t change the valuation. And so I have a hard time with pretty much all the explanations I’ve come across for why IPS might be sustainable.

Jeremy Siegel and his attempts to kind of, as ever, made a bull market that he loves. And the whole idea will work…What we’ll do is replace the kind of Shiller PE, tenure moving average with our whole economy profits instead. The problem with that is manifold, but not least of which is you don’t own the whole economy, you own the listed sector. That’s what you’re actually interested in. The big argument that kind of people use to attack the Shiller PE is, well, includes 2009, and 2009 was a dreadful year reflecting 2008. And, yes, that is true, but it actually doesn’t make that much difference. If you look at something like a Housman PE which instead of using a tenure moving average of reported earnings, says, “Let’s use the past peak cycle earnings.” You get exactly the same picture as you do with the Shiller PE. So, it has nothing to do with 2009 being included.

So, all of these kinds of arguments get thrown up all the time about why a particular metric is wrong or there’s some explanation. But so far, I have been completely unable to find one that actually kind of holds water that you can test empirically and say, “Yes, that is the case.” Like, with interest rates. If you look at real interest rates through history, and you plot them against, let’s says, Shiller PEs, you’ll find there’s no relationship. So, as compelling as it seems that the low-interest rates could justify high PEs, there isn’t a shred of evidence they ever have done, and therefore you’re acting on faith.

Meb: It’s funny because so many famous investors often recite this message where they say, “Equities are allowed to be more expensive because interest rates are so low.” And you gave a great example in one of your papers or books where you said, “Well, that’s funny. Let’s take a look around the world.” That hasn’t been the case in Japan for the past two decades, and Japan’s not some backwater economy, you know, number two, I think now number three economy in the world where they had negative returns for over two decades. So, but it’s funny that it gets repeated so much. And we, same thing, often used to tell people on Twitter, where I’ll say, “If you think interest rates matter and equity valuations as a model, send us one that works,” and I’ve yet to see one. So, listeners, if you find a good one, quantitative, send it to me and I’ll eat my words.

You know, it’s funny situation, though, because you have the scenario in the U.S. and almost all the conversations I have with individuals, we just went to a CIO summit last week and almost everyone agreed with this where they said, “You know what? We know that stocks are expensive.” And you had a piece where you talked about this and you say, “Fund managers, for the most part, all agree that U.S. market is expensive, but still they choose to own equities as cynical career risk driven position if ever there was one. I’ve been amazed by the number of meetings I’ve had recently where investors have said simply they have to own U.S. equities.” Maybe talk about a little bit about that concept and why that’s potentially pretty dangerous setup and position to be in.

James: Sure. So, you’re right. This is what I’ve described as this kind of cynical bubble where people know they shouldn’t be investing and, as you say, as kind of CIO conference that everybody is like, “Yes, we agree. U.S. equities are expensive.” And I had a bizarre meeting earlier this year on the West Coast of the States with a well-known endowment, and we spent 20 minutes running through all the valuations and they were nodding away and I was like, “Oh, this meeting is going really quite well.” And then we go to the end where we talk about, “What are you going to do? So, how are your positions?” They’re like, “Well, our CIO is screaming at us because we got 6% cash and meant to have 3. So we’re going to go and buy S&P 500 futures.” And this was not some individual investor who had no idea. This was a very sophisticated endowment and here they were behaving in exactly the way that we talked about here was cynical.

And to me, this is a very dangerous game because it implies that if you agree that the market is expensive but you’re still only equities, you’re saying they’re going up for some other reason. And that makes me nervous because it’s in essence you’re playing a greater fool game. You know, you abandoned the principles of investment. You should no longer call yourself an investor. You’re welcome to call yourself a speculator. I’m looking forward to the chief speculative officer’s offsite. That will be an intriguing one to be a fly on the wall there. But you can imagine that this is an environment which is very fragile because if it isn’t any valuation support and everybody agrees there isn’t any valuation support, then you are effectively saying the world is priced for perfection and you’re playing a greater fool game where you’re thinking, “Okay, I’m gonna hold on my equities for now because I think I can sell them even higher up.”

And we know that greater fool games are incredibly hard to win. Keynes wrote about it way back in the 1930s. He talked about the investment industry as a newspaper beauty contest in which the objective is not to the prettiest face, but rather to pick the face that the average person thought the average person would find prettiest. And you can play that game mathematically, and you say, “Okay, pick a number between zero and 100. The winner of the game will be the person who picks the number closest to two-thirds of the average number picked.” Now, when you play that game, you saw that spikes in these levels.

Meb: Whoa, James, let me interrupt you. Listeners, I want you to think of a number in your head and you can write it down on a piece of paper throughout the gem, just put it in your head. Think of a number that you think would be the best guess for this and you can see kind of where it plays out, by the way. All right, continue. Continue explaining the results.

James: It’s so cool. If you play this game, and I played it with over 1,000 professional investors, and it’s about the third or fourth largest game I ever played and the only one purely amongst professionals. But you get these spikes and these spikes kind of represent levels of thinking. So, you know, you get a spike at 50. These are what I’d call the kind of Homer Simpson’s of the investment world, and they’ve gone not 100, go 50. So, they’ve not shown an enormous amount of intellectual prowess in playing this game. Then there’s the kind of spike at 33 who think everybody else in the world is Homer. Then there’s the spike at 22 who think they’re pretty smart. And then there’s usually a spike down to zero.

And zero, you find all the economists, mathematicians and the game theorists of the world because only these guys are trained to think about these problems and solve them. And it turns out the only stable and actually equilibrium outcome is zero. So only when everybody picks zero is two-thirds of zero is still zero, hence, it’s the only stable outcome. But of course, it’s also completely wrong because you’re not playing a bunch of economists and game theorists and mathematicians. Generally, what you find is the average number picks in these games turns out to be around about 25, 26, which gives you a kind of two-thirds average about 17.

So, in the particular game I played, what we found was only three people out of 1,000 managed to pick under 17. And the point of that game was just to show how hard it is to be exactly one step ahead of everybody else, and yet that’s exactly what you’re doing. You’re just saying, “You know what? Yes, the equities are expensive but I know better than everybody else. I’m gonna carry on holding them. I’ll sell out before the top.” That’s a very hubristic statement to make. It’s akin to saying, “Yeah, I can pick the exact winning number in case it’s beauty contest.” It’s a very hubristic statement and one that is not supported by matters of evidence throughout history. People generally end up selling near the bottom and the top strangely enough.

So I think this is a very fragile market where you have this cynical career risk dominated behaviour where everyone is saying, “I’m gonna own equities, either because I think they’re going up more or because…” And this is, I think, a big influence on love of the professional investors, “I don’t want to look wrong in the short term. It’s not that we don’t think they are over-valued, we do. It’s just that all of my peers are holding this stuff and if I’m the only one who isn’t, and they do well again, I’m gonna look really stupid and I’d get fired.” And that’s why we often talk about career risk being such a dominant force in market behaviour because it is one of those things that forces people to do strange things like owning overvalued equities, which they know they’re doing, but they’re doing it because the fear of missing out it’s just so great.

Meb: You know, it’s funny. It kind of goes back to that old Charlie Munger line where he says… you know, I’ve heard Warren Buffett mentioned this many times where it’s not fear and greed necessarily that drive the market, it’s envy, and envy being that part where you have a market that’s appreciating in valuation, and particularly when it gets into the bubble phases, you know. The envy, if you’re probably a logical investor, rational maybe sitting it out and all your neighbours getting rich is really, really a hard thing to sit by while everyone else is having fun. You know, you talk a little bit about risk and volatility and how they equate and you have a chart that you’ve popularized that I love that I think puts it into a better framework for a lot of investors.

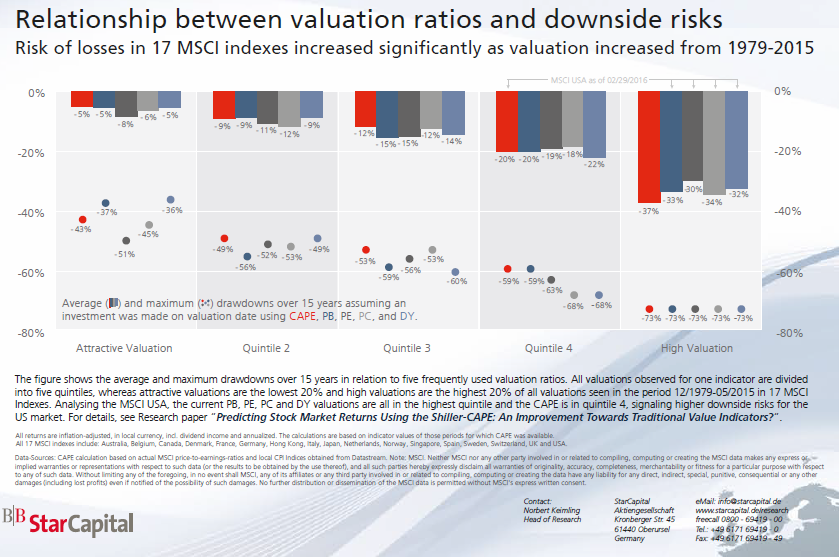

You know, so you all publish your forecasts and you say, “Look, you know, U.S. stock returns is probably gonna be negative.” But there’s a chart that looks at valuation and/or forecasts or valuation, but same thing and then future drawdowns based on that valuation. And maybe you could talk a little bit about that and what that kinda means because I think when people put it in terms of potential loss rather than yearly the returns may not be so good, but the actual magnitude is, it probably means something a little more tangible for a lot of people.

James: Yeah, I think it kind of triggers the fear of response much more, right? The idea is that, “Yeah, you’re gonna get low returns than you’ve had historically,” it’s just not that terrifying. So, when you look at the chart of drawdowns on the same basis and you plot the Ps on the market against the subsequent kind of three-year drawdown, you get exactly the same relationship kind of monotonic patents where the higher the market is, the worst the drawdown actually gets. And that’s not a huge surprise, but it really does reinforce in people’s minds that, “Hey, what I’m doing here is playing a very dangerous game.” When markets are priced for perfection, if they fall short against their expectation, the downside is really high, whereas if market is surprised to kind of really bad outcomes, then it doesn’t take an awful lot to exceed the outcome. And even if they’re disappoint, if people are really pessimistic, it’s hard to disappoint by that much. Then you can see it in action in kind of 2008.

So, in late 2008 I actually turned bullish which is a rare state of existence to me and I was really excited because I was running deep value screens, they’re throwing up really good names, even things like Microsoft repairing on a deep value screen. I never thought I’d get the opportunity to say, “Gone by Microsoft.” But if it’s a world in which people were picking up the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times every day and seeing stories about how the world could end tomorrow. And the reality was, from my perspective, “Look, if you look at the kinds of levels of evaluation we were getting towards in some places, this was the level where it was really hard to imagine a permanent repairmen capital on an ongoing basis, therefore, you’re wanting to deploy capital.” It didn’t make markets couldn’t go down more. Of course, they could. But as long as you had a sufficient time horizon, let’s say five years, then you will likely to be buying pretty attractive levels of valuation. The flip side of that is where we are today where markets are very expensive in general and particular in the U.S., therefore, the risk you are running is the drawdown is much more severe.

Now, it could be that this time is different that actually, we see a prolonged period of the market going side-wards, you’re still gonna get those value returns, you just don’t get the crash. We haven’t historically ever witnessed one of those situations, but you can never say never. But I think the power of the drawdown chart is it’s just really reminds people of, “Hey, when things get expensive, I run the risk of losing a lot of capital in a short period of time. And therefore, yeah, the more expensive the markets according to drawdown, that’s something I should really be worried about because I’m gonna…” We know that people, when they suffer losses, tend to really hate them and therefore they sell, and so it’s not just that they suffer the drawdown, it’s often that that triggers psychologically this kind of revulsion. People then sell at, of course, just the point in time when things are actually beginning to look a little bit better. So, the ignorance to that drawdown is not only the risk they’re running but the risk of then them changing their behaviour after that drawdown has actually occured.

Meb: And we’ll post this to the show notes, but there’s a great graphic where the guys at Star Capital in Germany extrapolated this not just from the U.S. but to a bunch of other foreign markets and you find the exact same behaviour where the more you pay for something, the higher the chance you have in the next three, five years of a big fat loss. Particularly, it gets even worse in some of these other countries because they’re smaller when they get to even a higher bubble sort of valuations, historically.

Sponsor: I wanna tell you a little more about Inspirato. Listen, you only get a few days off each year to spend with the people who are special to you. Aren’t these days too important to be left to chance? That’s where Inspirato comes in, the luxury vacation homes across the U.S., Caribbean, Europe and beyond. These spacious homes are staffed like five-star hotels, so you get all the amenities and on-site concierge and daily housekeeping. They even do the dishes for you. That’s why I became an Inspirato member. You can travel all over the world and get the same luxurious experience whether you’re in Nantucket, Sonoma, Spain or anywhere else.

Y’all know I’m a skier, so I can’t wait to check out their ski homes in Colorado and Montana. Members also get access to their joint program which offers incredible savings on luxury vacation homes and thousands of four and five-star hotels around the globe which is great for a business traveller like me. Let Inspirato take care of the details, you can focus on making the most of your vacation. Right now, our listeners can get $1,000 for their first trip to one of their exclusive vacation homes when they become an Inspirato member. Call 310-773-9474 and mention Meb Faber or visit inspirato.com/mebsentme to learn more. That’s inspirato.com/mebsentme. And now back to the show.

Meb: So, let’s say you got people listen to this and said, “All right, Meb and James, you’ve already ruined my morning workout. I can’t go to sleep tonight. What’s the… Give me the diagnosis. What’s kind of the prescription?” So, if you’re a longer-term investor, you know, I think the challenge for so many people is they want to think in binary terms, so either I got to be all in or all out. What’s the kind of prescription for what people should be doing if they recognize kind of some of the characteristics of what we’ve been talking about, particularly with U.S. stocks so far?

James: So, I think there are kind of four options that people could pursue. Not all of them have equal merit, but I think there are four options. And I will get through them and then we can talk about the kind of the favourite one out of the four if you like. The first one is concentration. You could just say, “You know what? I’m going to own the things that I am most optimistic about,” which in our case is emerging market value stocks. Now, we don’t think they’re particularly cheap, but they are a lot, lot better than pretty much anything else on the planet. So you’re still picking the tallest dwarf, you’re still saying, “Hey, look, this thing is expensive in absolute terms, but it’s a lot better than everything else.” So, that makes me slightly nervous on that particular approach, but you could go down that path, right?

So, a concentration is one way of doing it. And my boss, Jeremy Grantham, has talked a lot about the idea of the Stalin portfolio. And that’s kind of an extreme concentration portfolio. So, the idea there is Joseph Stalin comes up to you and says, “Hey, look, I want you to run my pension fund. What I want is 5% after inflation over the next decade in per annum terms. Off you go. If you succeed, you get a pension of your own and you get a nice little dock there on the Black Sea. If you fail, you get a bullet in the brain.” So, it really focuses your mind on kind of, “Okay, how am I gonna deliver that return objective?” If you were going to be Rip Van Winkel and sleep for the next decade, you would have to own emerging-market value stocks because that’s the only thing that gets you close to achieving that kind of return target.

I don’t think it’s a portfolio that anybody would run for lots of different reasons. One of which is the chances are, they’re not gonna Rip Van Winkle. They’re not gonna just fall asleep for the next decade. They cannot be looking at their portfolio and updating their views as they go. And that’s one of the problems with concentration is you kind of giving up the rights to rebalance terribly painlessly, because you’re saying, “Okay, I bought these emerging market value stocks, so let’s assume they get cheaper,” i.e., you’re wrong in the short term. You haven’t got any more capital to deploy, you’re kind of just trapped there. So, there are certainly limits to concentration, but it is one of the options.

The second option is to say, “Well, use leverage.” This is kind of the risk parity solution, if you will, that, “Hey, look, returns are low. To get better returns, what you need is to leverage up your portfolio.” Now, the problem I have with leverage is that it is largely incompatible with a valuation-based approach, right? A valuation-based approach is kind of what Howard Marks referred to as, “And I don’t know a way of investing,” by which he means that value investors are essentially agnostic about the path and asset takes. So, cheap assets can always get cheaper, expensive assets can always get more expensive at least in the short term. If you are using leverage, you are saying, “Hey, I know something about the past that this asset will take back to fair value.” That is a… It’s a difficult statement to make for a lot of value investors. It’s not one that I feel terribly comfortable with.

And you could look at someone like Julian Robertson, right? The value investing genius who ran Tiger back in the late 1990s and he shut his from down in 1999 because he was using leverage and the valuation-based approach. He was long value short growth and, of course, he was getting essentially killed on both sides of that right and eventually he just couldn’t be bothered to deal with clients anymore and said, “You know what? I’m just gonna shove it down to the public.” He continued to run it privately, did very well out of it, but the margin calls were pretty unpleasant as you can imagine. So, using leverage, you need deep pockets and you need a degree of confidence about the path that asset is gonna take, which I think too kind of big hurdles to overcome.

The third possible path you could say is, well, seek alternatives, right? So far I’ve talked about listed equities, listed bonds, currencies. What about all the other assets, private debt, private equity, all these so-called alternatives? The problem I have with alternatives is most of them are not genuinely alternative, by which I mean they are not magic beans. They’re not unicorns. They’re not somehow uncorrelated sources of return. Best example is probably private equity. If you think about private equity, what does private equity do? Well, it takes public companies and turns them private and then uses leverage. So, in essence, private equity returns in aggregate should be public equity returns plus leverage minus costs. So you can clearly see that the private equity is very much going to be a function of public equity. They’re going to be highly related. You know, if you’re looking for companies to take private, where are you taking them private from? Oh, you’re taking them from the public market. We’ve established the public markets are expensive, therefore, these deals are being done at expensive valuations and therefore your returns are likely to be lower.

So, I think as long as you think of alternatives as being different ways of owning standard risk, then you get an idea about what an alternative truly is. And just like every other asset or strategy, there will be times when it is attractively priced and times when it isn’t attractively priced. So, a good example that we hold in our portfolios, merger arbitrage. Merger arbitrage is a strategy that we think of as just like equity. It’s underwriting the same basic growth risk as equity investment, but it has a very different duration profile. Standard equities have duration, depending on how you measure it, it’s somewhere between 25 and 50 years. The duration for another draw of a deal is somewhere between about 6 to 18 months. So, it’s got a very different payoff profile. But it’s something you only want to engage in when merger arbitrage or the deals you can find are attractive, clearly. So, it’s valuation-dependent as anything else you do in investing, which leaves you with the final part. And this is my preferred path.

I’m a big fan of Winnie the Pooh. And actually, I used to live in the U.K. and I live very close where Winnie the Pooh was set. In fact, I even got married on Ashdown Forest where Winnie the Pooh was set. And I was reading Winnie the Pooh with my kids not so long ago and one of the pieces of advice in there was, never underestimate the value of doing nothing. And I think that that’s often neglected in our industry. There is an obsession with being seen to do something, action bias. Soccer goalkeeper suffer action bias. If you think about soccer goalkeeper and a penalty shootout, the ball is placed, the soccer goalkeeper standing there, he’s is in the middle of the goal. Usually what happens is they dive heroically left or right and they miss the site, right? The ball either go straight down the middle or to the opposite corner. The reality is, statistically, they will be much better off if they stayed in the centre of their goal, but, of course, if they do that and then the penalty get put in the corner, they look like an idiot. It’s like, “Well, why were you just standing there?” So, they would rather be seen do something, so they dive heroically left or right. That’s action bias.

And I think it’s very prevalent in our industry. Why are you sitting on cash? Why am I paying you to sit on cash? Which, of course, you’re not, right? You’re paying us not to do something stupid and going owning risk assets at these levels of valuation is becomes definition of doing something stupid, but patience is whilst it’s definitely a virtue, it is a problem because in the short term, it is indistinguishable whether you are just early or wrong, and therefore people’s tolerance for you tends to be quite diminished. And Keynes knew this a long time ago. He said, “Those who pursue kind of long-term valuation-based approach tend to receive very little mercy,” because if they’re acting in a contrarian fashion, which is inherently what a value-based investor is doing, they’re likely to look different, and looking different is career risk.

And so, it is unfortunate in the short-term because you’re sitting there, looking, let’s say, holding cash looking conservative, being patient, waiting for that opportunity set to change. If it doesn’t change, you are wrong, and if it does change, well, nobody’s gonna thank you anyway because they probably had a lot of investments that were once worth a lot more than they are right now, and therefore you’re not gonna be terribly popular. So, no matter what you do, you’re kind of doomed and that I think is one of the challenges to being patient. But to me, it is the most sensible thing to do when there is nothing to do, which is I think a good description of the current asset environment in general. Don’t do very much, right? Just sit there, be patient, wait until a better opportunity set present yourself that the risk you’re running, of course, is in never doubt.

Meb: The more years that go by with me and markets, the more I think that, you know, there’s certainly absolutely nothing wrong with cash. And people erring on the side of having more cash are never gonna really regret it as much as the people that do the opposite. And you had a couple good comments in some papers that tie back to what you’re talking about. You know, you said that, if you look back in the history of investment, it seemed like people really started from the standpoint of a blank slate, “Why should I own this investment?” but really it’s transitioned over the years to being more kind of a “Why shouldn’t I own this investment?” And on aggregate most of the academic literature shows that all these big huge, massive institutions that invest real big money, they end up owning the global market portfolio anyway. But so, here’s the challenge when we’re thinking about expectations, almost every study shows that investors expect 10% plus returns. The dang millennials are up around 12 because they’ve never seen a bear market.

And so everyone is focused on performance. And you had a good quote in your little book of “Behavioural Investing” where you’re talking about baseball, but you then segue this to say, “We obsess with outcomes over which we have no direct control. However, we kinda do control the process by which we invest. As investors, this is what we should focus upon. The management of return is impossible, the management of risk is illusory, but process is the one thing which we can exert and influence over.” Maybe comment a little bit about kind of developing a good process. You mentioned this poor opportunity set today and kind of how it’s hard, but you also talk about in “I Want to Break Free,” you said, “Clients really should be looking for managers that is based upon not past performance, but rather process and then kind of let them have at it.” Maybe any comments or thoughts you have there? We can go.

James: Sure. Absolutely. So, process is key, right? And you see this with athletes and, as you said, I talked about baseball in one of the notes there. But you talk to professional athletes and they’re not thinking about winning as counterintuitive as that seems given that that is what they are obsessing about at one level. It is not what they focus on because they can’t control it. The only thing they control is if it’s a sprint the way they run their race. And so, process is key. It is the one thing that everybody can control. And having a good process, I think, is no guarantee of good return, it just puts you in the best place to get kind of those good returns. It doesn’t guarantee them, but at least if you keep doing the right thing and do it repeatedly, eventually, it should lead to better outcomes. From an investment point of view, process is really kind of behavioural self-defence. It is saying, “Okay, look, I’m human, therefore I know I’m gonna make behaviour mistakes,” and there are a huge range of them. The psychologists have spent decades and decades documenting how we all think oddly about certain things.

The key is to think…is to say, “Okay, let me look at the way I invest and identify a couple of the big mistakes I keep repeating and then think about how I might begin to protect myself against those.” So, early we talked about confirmatory bias and the habit of looking for information that agrees with us. It’s incredibly easy to do. I think these days it is perhaps the easiest it has ever been to do because with everybody reading online media all the time, it is very easy to only look for the opinions that happen to agree with you. If you tend to stumble across somebody who disagrees with you, you dismiss them as a jabbering idiot, anyway. That’s all what they know, and then you retreat back to the reading the stuff that you agree with. That has made a lot easier today by the way that we can handle media in an online setting. So, I think confirmatory biases is certainly a big risk.

So, getting into the habit of saying, “Where can I be wrong? What would it take me to be wrong? How can I set this problem up so that I’m exploring the opposite point of view in an objective fashion?” And it crops up throughout all of human behaviour. These biases are pretty constant. There’s a great book by Brian Wansink called “Mindless Eating” which I love. And it’s all about how these biases show up in the context of food. And he had one where there was a refillable soup bowl, so people are eating soup at a restaurant table. What they don’t know is the bowl is actually refilling from underneath the table, so they’re not making any dent in it and they massively overeat because they’re just completely unaware of the fact that they’re just consuming more and more soup. They ‘re like, “My bowl is still full. I must eat more.” Totally oblivious.

There was an experiment done where they put red food dye into white wine and people were like, “Oh yes, I can smell tannins and oak and heavy redness.” And they’re like, “You idiot. It’s white wine with red food dye. It’s completely false.” But it’s these perceptual biases and behaviours show up in every aspect of life, and investing is gonna be no different. And so, thinking about how you build an investment process that is at least robust to some of this, I think is very important. So the way we do it, or one of the ways we do it, is by putting valuation at the very heart of everything we do because we know that we are human beings. So, we’re gonna pick up the newspapers and sit there and see these stories about either how good everything is or how bad everything is, depending on where we are, and you’re going to start to kind of build that in.

Having the advantage of a valuation-based framework is effectively turning a behavioural bias which is anchoring, hanging on to kind of sometimes irrelevant information as the basis of decision-making and actually turn it to your advantage. So, a good example of anchoring with some German judges, and they were asked to sentence people to jail. But before they did so they had to roll some dice. And the dice were rolled and they were rigged. So they either gave the answer of three or nine depending on which set of dice are being used. And what was interesting was the judges’ sentences were directly proportional to whether they happen to roll a three or whether they happen to roll a nine irrespective of the situation of the crime. So, the judges, without knowing it, are actually anchoring to this irrelevant piece of information.

So rather than anchoring to new stories or value at risk models, think about anchoring to valuation, because then, let’s say, the world falls apart like it did in 2008, 2009, early 2009, you’re sitting there, you’re looking at valuations, you are going, “Wow, this is a tremendous opportunity. I can buy assets that are 10, 11, 12 real.” Conversely, in 2007, you’re sitting there going, “I don’t want to own assets because these things are hideously expensive. Why would I wanna go and buy some? So, it doesn’t make any sense to go and buy in that kind of environment. I’m gonna keep my powder dry and go and invest when the opportunity set is better.” So, that valuation framework helps you have an anchor that is actually sensible rather than clinging on to something that is essentially random noise like the newspaper headlines. So, I think you can do that in lots of different ways. You could do it with stock valuations as well. So, rather than building a dividend discount model or discount cash flow model where we know…

I used to work, you know, with analysts for a very long time, and I knew the way they built their models. They’d look at the share price and they go, “Oh, I want to be a buyer. I need to have a share price target that’s 10% higher, therefore I’m just gonna notch my growth up until I get my DCF to be 10% higher than current price. So, you know that they’re not using a DCF in a sensible fashion. Rather than falling into that trap, reverse engineer the problem. So, say, “Okay. What do I need to believe to justify today’s valuation in terms of growth?” And then have a conversation around whether that growth is actually deliverable or not. And one of the things I do is I plot a histogram, if you like, of all the companies in history that I get my hands on and show where their growth rates are, and then I can say, okay, well, let’s say I pick a stock and it’s in the 99th percentile, “Why do I think this stock is gonna be in that 99th percentile?” Whereas if it’s down in the 5th percentile, I’m like, “Well, pretty much everybody hates this stock. It’s really beat up. What could go wrong? And let’s have a conversation about the risks.”

But in general, I should be pretty much predisposed to that because expectations are very low. So, it’s a good way of kind of flipping the problem of anchoring to the share price on its head. So, these are all kind of good elements of process that can try and make you behaviourally robust. We talked about triangulations, looking for different signals and seeing if they all agree, you know, that makes you more confident. That’s good. Right? If they’re all different, you gotta be a little more circumspect about your outlook. So, I think process is vitally important because it’s the one thing an investor can control and really help them admit that that their own worst enemy is likely to be themselves.

Meb: You know, it’s funny. I just had a conversation with a fairly well-known investor the other day, and he called me, we’re walking through our funds, he goes, “Okay, Meb. Tell me, what’s your best fund? Which fund…” He goes, “Which fund has the best performance?” And as soon as he said that I closed my eyes. I was on the phone, so he couldn’t see me do this. You know, facepalm and… because I just knew where this is going. And I said, “Okay.” But I try to be good sport, I said, “Okay, just out of curiosity, like performance over what timeframe? Are you talking about one month, one year, three years, five years?” And he goes, “Oh, you know, like, I’m an rules-based investor.” He’s like, “Tell me your best risk-adjusted performance.” I was like, “Do you want it absolute? Do you want it relative to the benchmark?” And he goes, “Okay, both. Give me absolute best.” And then I go, “Just out of curiosity, like, I assume you’re asking me this because you’re looking for the one that has the worst trailing three and five-year performance, you can invest in that one, right?”

And he said, “No, why would I do that?” I then, “Okay, well, with this whole framework is backwards because you’re gonna end up doing what every institution does, which is chasing performance.” And it’s so seductive and easy and it’s one of the reasons I became a rules-based one is identified I have all of the behavioural biases, and in some in spades. I’m overconfident, I’ll take as much risk as you could possibly give me, but listeners will post a link to one of James’s old tests that have some pretty famous behavioural questions and you can see just how many you will have and get wrong. It’s a lot of fun. And then once you do that, you say, “Man, I…” You then see it everywhere amongst your friends and family and everything else.

All right. So, we can’t hold you forever. I’ve got a couple other quick questions I wanna touch on before we gotta let you go. James, it’s been a lot of fun. Do you think we’re in a bubble? You know, you talked a lot about this. Your shop is a very famous curious mind, student of history shop that looks at bubbles across currencies, equities, bonds, everything in between. As you look around the world today, are you seeing any U.S. stocks, anything else?

James: I think so. I think it’s really interesting. There’s a lot of debate at GMO on this subject. So, Jeremy Grantham is on record as saying he doesn’t think it’s a bubble and primarily doesn’t think it’s a bubble because we are lacking euphoria. You know, you’re not getting in the back of cabs and hearing people saying, “Oh, well, what’s your stock tip?” I guess the most pure form of that kind of mania is probably the cryptocurrencies where towards the end of last year we were genuinely hearing that kind of thing. People were like, “Oh yeah.” We have one person call up and he was a rock basis for a well-known rock group and he was generally thinking about putting all of his savings into bitcoin and we were like, “Really? That’s brave. Here’s why we wouldn’t do it. We think it’s a mania and laying that out.”

I think this is a different sort of bubble. This isn’t a classic mania bubble in the euphoria sense that Jeremy refers to like ’99 was. That was a popular belief. People genuinely thought the world was gonna be different and in fairness, technology did change the world. It’s just not necessarily in a hugely profitable fashion for a lot of people. So, I think that was a very different bubble of belief. This environment we’re in today is why I refer to this as a cynical bubble, is very different. It isn’t a bubble of belief. People don’t believe what they’re doing, but they’re doing it anyway. And so, I think this is a bubble, but it’s a different one from the classic manias, the bubbles of belief that we’ve seen.

Meb: Yeah, I tend to agree. I mean, we look at the huge potential spread between expectations and probably reality. And I’m fine with the buy and hold crowd. I often tell, I say, “Look, we run one of the world’s cheapest buy and hold funds.” I say, “It’s totally fine but you have to understand where you’re getting. For example, at least understand the stocks have declined 80% before.” And the challenge I always have, you know, as Jack Bogle, I think he’s a national hero for all that he’s done, but he says, “Look,” in a recent paper he said, “I expect U.S. stocks to do…” I think it was 2%, maybe it was 3% a year. So, pretty darn low, but he also said, “You remain invested.” And I’ve always wanted to ask Jack and Warren and the others that say, “You just got to remain invested,” say, “There’s got to be a point at which you just say enough is enough. I don’t know if it’s a PE of 50 or 100 or 200 or 500, but at some point, it just makes no sense to me.”

Let’s talk about a couple of other quick things and then we’re gonna let you go. This is a total sideways segue. So, just total reset, but this is something that I think is another market myth that so many people get wrong on such a consistent basis that I think is probably useful just to spend a couple minutes on. And it’s less about investing and more about macro. So, you’re kind of a reformed economist. But you did a paper a couple years ago talking about market macro myths, deficit, and delusions, and there was two, in particular, I wanted you to touch on it if you’re okay with it. One is, you talked about debt with governments are like households. And the second being, debt is a huge burden on future generations. Maybe if you could just kind of explain your views on those real quickly because I think it’s particularly helpful for people as an example of their echo chamber and at least seeing something where, you know, what they’ve heard on TV may not be reality.

James: Right. It’s the very reason that the genesis of that paper was exactly that kind of… I was getting really annoyed by people bouncing and repeating these kinds of things without really thinking about them. And the first was, yeah, the households and governments are very different. So, if a household takes on debt, it has to repay it, it has no choice, right? And it’s a real asset transfer. If a government issues a bond, it will repay it, but it has a very different way of repaying it. It owns the printing press. It will always be able to print money to repay its debt. And that’s a very different dynamic. So, a government’s debt is very different from a household’s debt, and yet a lot of the analogies you hear, you know, “We’re living beyond our means,” those kinds of things that the fiscal position is unsustainable. There are really ways of kind of taking the household view of the world and imposing it on governments and they’re very different things. A government actually doesn’t have to issue debt at all. It is perfectly possible that a government could just finance all of its spending through printing money.

And the very term of printing money it’s going to send shivers down people’s spines and they start thinking about, you know, the Weimar Republic or Zimbabwe, or some of these kinds of examples. But it’s not that the printing money is per se a way of generating hyperinflation, it isn’t. Hyperinflation are actually generally associated with huge supply shocks. In the case of the Weimar Republic, it was the fact they had to pay repatriations to the Allied forces and had to do so in hard currency, so they had a huge supply shop and also, of course, had lost most of their capital output through the loss of the war. And in Zimbabwe, with the output shop, it was really about a huge amount of the transfer of not being able to produce their own food, which they used to be able to do and then didn’t because they decided that they weren’t gonna bother running the farms. There was a huge output shock and they had to go and buy food on the international markets and that was printed and that was denominated in dollars, so suddenly they had this huge debt burden that they weren’t expecting in the currency that wasn’t their own.

So I think people kinda hear the words printing money and panic. But if you think about it, a government can print money and just not issue bonds and say, “You know what? We don’t need a bond market.” No way, for instance, has a bond market, essentially, for fun. It doesn’t need one. It has a huge sovereign oil fund. It doesn’t need to go out and actually, if you bond, but it does so if it thinks there is some convenience to having a government bond market, but it is perfectly possible for a government to always repay its debt, assuming those debts are issued in their own currency. Where you get into a different situation is if you are issuing debt in a currency that isn’t your own which is one of the issues for the Eurozone. So, that is one of the big differences between households and governments. And I think people use these household analogies as an example of a way of kind of forcing a set of political beliefs on people that actually at odds with the economic reality.

The other one that you mentioned was kind of this future debt as a… I’m sorry, debt as a burden on future generations. When you think about it, who do you owe this debt to? So, you know, if you’re talking about U.S. debt, let’s assume just a minute, we’ll make this simple, that all U.S. debt is owned by U.S. citizens. So, that debt, when it gets paid, is paid to U.S. citizens. It’s a debt we owe ourselves, not anybody else, and it isn’t an intergenerational transfer because the assets are still gonna be there. I think they can run the money and there isn’t any intergenerational aspect from it. It’s just a myth that there is this tremendous burden on future generations because they also own both the asset and the liability. And as we know, from any asset and liability, they have to net to zero.

Now, it is perfectly possible that there are big distributional consequences to that. It might be that, you know, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett’s grandchildren end up owning all of the assets and everybody else has the liability which is unfair in lots of ways and it’s not necessarily a good outcome, but it isn’t about intergenerational transfer, it’s a cross-sectional transfer, so within society transfer, not one where they have the baby boomers who are suddenly gonna impose this huge burden on the millennials. It’s one of those classic bits of nonsense that get spoken. People kind of believe because it seems compelling and obvious, but when you actually think about it, it’s just total nonsense.

Meb: Yeah, I think you framed it and this is a great way to think about it. This may have not been you, but I’m gonna credit you with it anyway. Because it said, you know, if we just behaviourally change the phrase from national debt to national savings, it would probably change people’s perspective. I remember watching Mr. Robot once in the first season, and you know, the premise was he’s like, “All right, we’re gonna do this bug and it’s gonna get wiped out all government debt.” And say, “You moron. You’re also wiping out your grandmother’s savings, your father’s pension plan that invests in this debt. You know, you’re wiping out your brother’s Illinois retirement plan,” and all these examples of people forget that it’s actual savings as well and it’s asset-liability match.

Okay. Two more quick questions, we’re gonna have to let you go. This is one we ask everyone. We say, “As you think back, wind back to your early days, recent, late, whenever it could be, what’s been your most memorable personal investment?” It could be great, it could be terrible, it could be a trade, it can be anything. But what’s the one that kind of pops in the head as being the one most memorable in your career?

James: So, the most memorable in my career is a mistake, and it was in probably about 1995, ’96, somewhere around about there. I was busy looking at Japanese bonds and they were yielding something like 3% at the time. And I wrote an analysis saying that there was no way on earth Japanese yields could ever go lower. And I watched them halved, halved and halved yet again, and really that triggered a lot of thought after they halved like four times, into, one, I just managed to get it so horrifically wrong. And that led me to that piece that I wrote on debt, deficits, and delusions because I was kind of… I was, at that time, using a very kind of standard way of thinking and hadn’t really kind of questioned anything. And so when I went back and questioned, I was like, “Jesus. Yeah, I just completely coughed that up.” It was a terrible, terrible idea, but it was a very humbling experience. And the markets have an amazing gift for reminding us of the need to be humble on a regular basis.

Meb: That’s the famous widow maker. At least you didn’t go short these bonds.

James: It is, I know. Yeah. Right. Yes, it could have been familiar as well.

Meb: But that’s such a good example to have markets doing things that, you know, you don’t expect. I mean, seeing for, at least me personally, seeing negative yielding sovereign bonds has been interesting eye opener that I wouldn’t have even thought possible, you know, probably 10 years ago. James, I hear you got your Deadpool fanboy outfit on today that go see… You already seen the movie? You’re getting ready to?

James: I have seen it. I went to see it last week.

Meb: So, are you a Marvel or DC guy?

James: I’m a Marvel guy. I think DC used to make really good stories, but they make terrible bloody films. And Marvel, I think have just managed to nail the combination of that transition from good stories to great cinema.

Meb: You know, I grew up as a comic collector. The most decent thing my parents ever did to me they said growing up. You know, we grew up in a typical middle-class family, they said, “Meb, the only thing that you’re allowed to spend whatever you want on is books,” and so I took books to mean comic books and proceeded to then sign up for about 20 different comic book subscriptions. And about a week later, every day in the mail comic book showed up and they just kind of smiled and said, “Look, you know, you got us on this one.” So, my mom to this day, bless her heart, she’s the number one podcast listener. Hey, mom. She is storing about, I don’t know, let’s call it 4,000 comic books in her basement where the best lesson on this all together was that, you know, I said, “Maybe they’ll be worth something someday, who knows, or kids would want them.” And then she dug out some like Lone Ranger, not even Loan Ranger, something like Western comic book she had growing up and the four of those were probably worth more than all 4,000 of mine put together and not even close. So, goes to show, she’s the best investor in my family. James, it’s been a blast. Where can people find your writings, follow you? What’s the best place?

James: It’s all on the GMO website which is www.gmo.com. You can register for free and pretty much everything is on there.

Meb: Awesome. James, thanks so much for taking the time today and enjoy the Deadpool movie.

James: And it has been a real pleasure, Meb. You keep well, my friend.

Meb: Listeners, it’s been a blast. We’ll post all the show notes on mebfaber.com/podcast. We now, our preferred app is Breaker. Check it out. And if you like the show, hate it, leave a review. Let Jeff and I know, feedback@themebfabershow.com. Thanks for listening, friends, and good investing.