Episode #108: Radio Show: What’s More Important – Savings or Returns… What Meb’s Doing with U.S. Bonds… and Listener Q&A

Guest: Episode #108 has no guest but is co-hosted by Jeff Remsburg.

Date Recorded: 5/24/18 | Run-Time: 50:17

Summary: Episode 108 has a radio show format. In this one, we cover some of Meb’s Tweets of the Week and various write-in questions. After giving us the overview of his upcoming travel, Meb shares his thoughts on our recent episode with James Montier. It evolves into a conversation about the importance of “process” in investing.

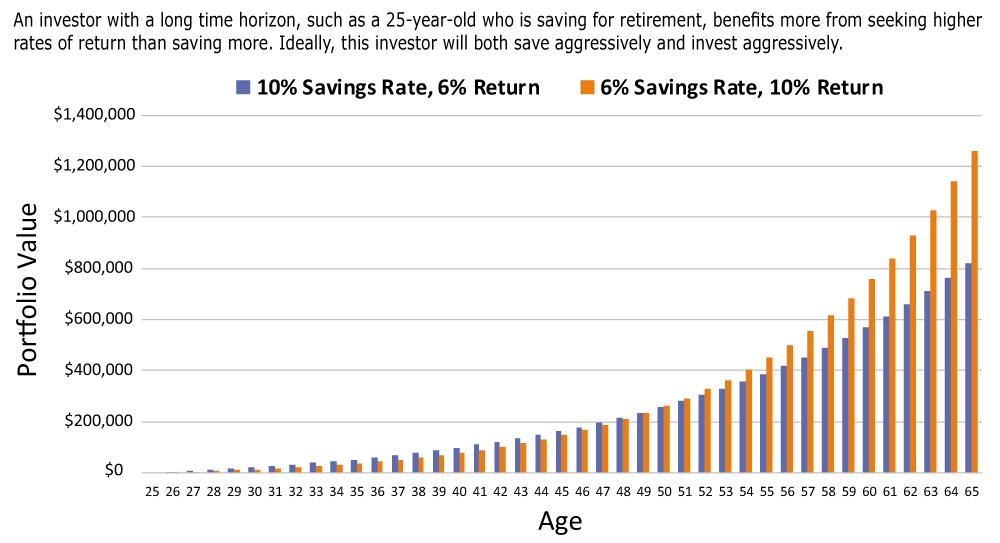

Next, we talk about a Tweet from Meb which evaluated what matters more – your savings rate or your rate of return. As you might guess, in the early years, savings trumps, but for longer investment horizons, rate of return is far more influential.

It’s not long before we jump into listener questions. Some that you’ll hear Meb address include:

- What is the best way to include commodities in a portfolio? Specifically, is it better to have an ETF containing futures contracts or an ETF containing commodities equities?

- Obviously historical returns from bonds, especially the last 40 years, will not be repeated in the future. How will you position yourself personally – not Trinity, but personally – for the bond portion of your portfolio?

- What are some viable simple options for individual investors besides having a globally diversified bond portfolio? Or is global diversification the answer? Is the global risk somehow less risky than a U.S. bond allocation?

- Star Capital studies and your book show that ten year returns of low CAPE ratio countries are impressive. But it doesn’t tell if those returns occurs gradually, or if the path to this performance is just noise and cannot be predicted. If the path is noise, it would make sense to buy a cheap country ETF and wait at least 7-10 years. But your strategy rebalances every year. Why not hold longer to 7-10 years in total?

- I recently read that 88% of companies that were in the S&P 500 during the 1950’s are no longer in business. If every company is eventually heading towards zero, why are so few people able to make money on the short side? Shouldn’t the ideal portfolio be long the global market portfolio, with tilts to value and momentum, and short specific individual equities?

- I’ve looked at you Trinity Portfolios and noticed an allocation of 0.88% to a security. Why? Isn’t the impact neglectable?

- Do you suggest someone get a second opinion on their financial plan much as someone would get a second opinion for major surgery?

There’s plenty more in this episode including data mining, trend following time-frames, and what Meb’s thoughts are on ramping up equity exposure in a portfolio to offset the effects of living longer.

Comments or suggestions? Email us Feedback@TheMebFaberShow.com or call us to leave a voicemail at 323 834 9159

Interested in sponsoring an episode? Email Jeff at jr@cambriainvestments.com

Links from the Episode:

- 1:37 – Meb and Jeff’s European vacation

- 2:56 – Highlights from the James Montier Podcast Episode and the importance of process

- 3:25 – The Little Book of Behavioral Investing: How not to be your own worst enemy – Montier

- 3:35 – The Little Book of Safe Money: How to Conquer Killer Markets, Con Artists, and Yourself – Zweig

- 3:41 – James’ behavioral tests: hereand here

- 7:39 – Why do people, even smart investors, still chase performance

- 9:09 – Some processes that would help investors

- 9:30 – “The Zero Budget Portfolio” – Faber

- 11:15 – How much weight does Meb give to time-frame when doing market analysis

- 13:59 – Rob Arnott Podcast Episode

- 16:04 – Listener question: Should people have a second opinion on a financial plan the way you would for a medical opinion

- 21:02 – What matters more, savings vs return

- 22:09 – “The Best Way To Add Yield To Your Portfolio” – Faber

- Graph of “savings versus return”

- 24:00 – Paul Merriman Podcast Episode

- 25:30 – How do you reconcile the idea of saving more against reducing quality of life

- 28:53 – Listener question: Best way to include commodities in the portfolio

- 31:44 – Do commodities provide a portfolio with Alpha

- 32:53 – Listener question: How will Meb position his bond portfolio and what can average investors do to remain diversified

- 38:33 – Listener question: Why Meb rebalances every year in some of his funds versus holding for 7-10 years

- 40:47 – Listener question: Why aren’t more people successful at shorting

- 42:47 – “Even God Would Get Fired As An Activist Investor” – Gray

- 44:19 – Listener question: Given the performance of stocks over the long term, why not have a 90/10 portfolio

- 46:13 – Listener question: Why such a miniscule allocation to certain stocks in the Trinity portfolio

- 47:50 – Listener question: Using the 8-month back-tested moving average over the 10-month

Transcript of Episode 108:

Welcome Message: Welcome to the “Meb Faber Show” where the focus is on helping you grow and preserve your wealth. Join us as we discuss the craft of investing and uncover new and profitable ideas, all to help you grow wealthier and wiser. Better investing starts here.

Disclaimer: Meb Faber is the Co-founder and Chief Investment Officer at Cambria Investment Management. Due to industry regulations, he will not discuss any of Cambria’s funds on this podcast. All opinions expressed by podcast participants are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of Cambria Investment Management or its affiliates. For more information, visit cambriainvestments.com.

Meb: Welcome podcast listeners. It is late May. We’re getting ready to roll into summer, and so we’ve had a whole slew of great podcast episode guests with most recently, James Montier, Ken Fisher, Olivia Judson, Brian Singer. So it’s time for a radio show, you guys, were emailing in, pining for Jeff, so Jeff, welcome back.

Jeff: What’s going on?

Meb: Did you feel a little lost in the woods not having been on the show in a while?

Jeff: You know, I mean, I’ve been enjoying my time in the sun away from this. There’s just so much limelight. I have such a big fan base out there, it’s hard for me to live in all that, sort of, just glory.

Meb: Well, listeners, as you know, we’re getting ready to head to Europe, so maybe we should bring along a portable recorder and record some live-from-Europe shows.

Jeff: You’re right, and I’ll let you do that while I’m on the beach.

Meb: Give you a little Ouzo, little Chianti. What are we talking about today, what’s going on in the world?

Jeff: Well, why don’t we start off by you reminding everybody about the travel in case they wanna try to get a hold of you over in Europe.

Meb: This is a fun trip, this is a wedding, college friend, but, as always, love meeting up with people. And we’ll be in Greece and Italy, maybe London for a little bit, but we’ll probably back in Europe later this summer so TBD, but exciting. Except for the part where I’ll be confined to an airline cabin with my one-year-old, first time over like an hour on the plane. I’m quite nervous.

Jeff: But, at least you’re bringing a nanny though, that’s gonna help out significantly.

Meb: My nanny is named Jack Daniels.

Jeff: Your manny?

Meb: Yeah my manny.

Jeff: All right. So, let’s do this. Let’s chat about a few of your Tweets, and then let’s dive into some listener Q&A. How does that sound?

Meb: By the way, podcast listeners, I switched to a new podcast app. I’m trying out Breaker in my never-ending search for a podcast app that lets you rate shows. So, you guys try out Breaker. If you know something better…

Jeff: Explain to the listeners why you like it better like you did me the other day.

Meb: I don’t know that I like it better, but it’s the only one that even allows for likes at all, so you can sort shows by what people are really enjoying.

Jeff: But it’s still pretty new where the likes aren’t… It’s just…

Meb: [inaudible 00:02:49] hard.

Jeff: They’re not totaling that much right now, correct? I mean, I saw…

Meb: Yeah, I don’t know how many users they have, but, anyway, it’s a never-ending search.

Jeff: All right, so let’s… Number one, real quick, we just did Montier. I thought it was a great episode, anything stand out in particular to you from that podcast?

Meb: I mean, he’s fun, you know, there’s the type of guest where I could just push play and he could go for an hour and just shut it off for two hours or five hours. And I have corresponded with James over the years many times and very familiar with his research, read all his books. If you want a great introduction to behavioural investing, he’s really written the kind of Bible, it’s like 700 pages, but there’s a shorter version he did one of the little books on behavioural investing.

Jason Zweig has got a really wonderful behavioural investing book too, but they’re both great books, and I think we posted on the show notes. There’s a really fun behavioural test that has about 20 questions that shows you just how many of those crazy behavioural, sort of, weirdness that everyone has. And you don’t think you have them, you take the test, you’re like, “Oh, my God, that’s embarrassing.” Anyway, but we talked a lot…if you haven’t listened to the episode, go listen to it.

But, we talked a lot about performance and market valuations, but also process. And he had a really good quote in the podcast where he said something along the lines of “Process is behavioural self-defence.” And behavioural meaning there so many dumb things we wanna do when investing, but if you have some sort of codified process it makes life so much easier.

And let me give you a good example. This is a conversation that I have almost every day with an investor, and not just individual, I had this conversation with a professional investor about a week ago. But it seeps into every single area of investing, and we’ve talked about this 100 times on the podcast. But just to tie it back. And was chatting with this very well-known investor, and were walking through the funds and he goes “Okay, Meb. I just wanna hear about what’s your best fund?” And I said, “Well…” “Which one has the best performance?” And as soon as he said that, my heart just sank.

And the reason my heart sank was because I knew where this was going, and as an asset manager in fiduciary, there’s two ways to answer that question. The one is tell them what they want to hear, so I can say, “You know what? We managed this fund. It was up 20%, 2 years ago, it was up 30% last year, it’s doing awesome this year. This is why it’s awesome. This is why you should go buy it.” And of course, they’ll go buy a big slug and this guy… I mean, a lot of these institutions are moving in $10 million plus portions.

But one, you’re selling a little bit of snake oil, and two, you’re acting like all these funds have in sales been for the last 30 years. They’re telling people what they want to hear, regardless if it’s right for them, and then, second, it’s not gonna be a good investor because it’s gonna be hot money. So the conversation continued, of course, I can’t help myself so I’m not gonna play that game. So I said, “Okay, so just to be clear. When you’re talking about performance, like, do you mean over what time frame, do you mean like a month, a year, inception? Do you mean absolute terms? Do you mean relative to a benchmark?”

He goes “No, no, no. It’s basically…” I forget what he said, but it was basically like “I’m not new, but like I want the best risk-adjusted returns.” So that sounds slightly more sophisticated, but it’s not. And this is where I always almost get hung up on, I say, “Okay, I can tell you, but I’m assuming, you know, because you’re a professional investor and you know better. I’m assuming that you’re asking because you’re looking for the fund that has the worst trailing three-year performance. Because as we all know, asset classes go and strategies go in and out of favour, and so if you just believe in that process of the asset strategy in the first place, then what you probably wanna be investing in is the one that has the worst performance, right”

Jeff: Mean reversion.

Meb: And it’s just quiet. And he’s, “No, why would I want…” and I, you know, this is just where it goes. But, the whole point is if investors could blind themselves to charts and performance of what’s happened in the last year or three years, and just said, “Look, this is what my process is gonna be. They’d be infinitely better.” But everyone gets attracted by that shiny little light that whatever the hot story and fund is of the day. And so I think Montier really spoke to this with his comments, but particularly that having a process really keeps you from…and there’s so much research.

I mean, we’ve cited it a million times on this podcast already about how the institutions…all the academic literature shows that they make all the same mistakes. They allocate to funds that have great trailing performance, and sell the ones that have horrible trailing performance, and they were doing much better staying with the old fund when they made the switch.

Jeff: Why does that… I’m assuming this individual is obviously probably very intelligent, and has been around the markets for quite a long time. Given that, how does that market belief still manifest? How is it still around?

Meb: I think there’s a number of reasons, ones is in our podcast we did on the investment period which the article was still in production, but should be out soon, listeners. People love spending all the time… Like I go on TV, I was on “Bloomberg” prior to this show, and the pre-call’s like “Hey, you wanna talk about Turkey? Turkish Lira is getting cheap.” By the way, we should go over to Turkey when we’re in Europe. The currency is making life much cheaper as a tourist. Stock market’s also getting a lot cheaper, by the way.

Jeff: Brian talked about that, I believe. I think he was referencing currencies, and I think he mentioned Lira.

Meb: Stock market is probably single digit p at this point, but, you know, people love talking about the very tops of the pyramid, but what really matters is you get all the basics right in the first place. And so, you know, I think a lot of it’s the behavioural nature, like it’s genetically wired into investing like that, and unfortunately, it’s not a smart thing to be doing.

Jeff: That just doesn’t make sense to me that you’d be around the markets this long and not be able to, sort of, curb yourself like that. Okay, but that’s…

Meb: Well, you’re still trading options, so, you have some behavioural biases too, it’s just different ones. Self-delusion…

Jeff: Of [inaudible 00:09:00].

Meb: Delusions of grandeur.

Jeff: So we talk about process, and I’ll put you on the spot here a little bit. We haven’t really prepped for this, but can you think of two, three, four, very broad brush processes that would help somebody when they think about what the process is, what does that mean to you?

Meb: I love you said we didn’t prep for this as if we prep for any of the radio show.

Jeff: Well, this particular line of questions.

Meb: You haven’t prepped for this. So yeah, I mean, we’ve talked about this. My favourite was the article we worked on together, what was it called? “Zero Budgeting Portfolio.”

Jeff: Something like that.

Meb: And the concept was, hey, look. If you were to start your portfolio with a blank piece of paper and write down how you’d invest starting today, and if that doesn’t match your current portfolio then something’s out of whack. Ignoring taxes, but most people even don’t think about taxes at all anyway, and so that would be a start. So what’s your base case portfolio, and then what your base case…so policy portfolio, another way to explain it, institutions call it. Then how do you plan on updating it? Are you just gonna re-balance once a year and that’s it? Done, that’s fine. Are you going to make these changes based on xyz? That’s fine too, but try to codify them ahead of time.

You know, a lot of people they have this emotional tie to their old portfolio for whatever reason. And so we were talking about this on Twitter the other day I said, “Hey, go type in all your old school mutual funds, these high fee ridiculous funds into your…there’s a website called FeeX, is one for example. Where you can type the funds in and it’ll show you cheaper alternatives, then I am referring to kind of the buy and hold beta this point.

Obviously, we’ve said a million times that all that matters is net returns after all fees, taxes, expenses, everything altogether. So there are certainly are funds and strategies that are worth net-of-fee returns and gross expenses, but it’s a high bar. So, anyway, you know, I think just codifying the process in the first place and a lot of people… I would say 99% never make that first step. They just shoot from the hip and kind of play it by year and that’s horrible way to invest.

Jeff: Kind of tying back to the question or to the issue of the guy asking you about the best performing fund, and one of your possible responses was gonna be, “Well, I assume that’s because you wanna know you know, which one not to invest in.” So the flipside, let’s say that you’re looking at worst performing funds. Do you ascribe…

Meb: Commodities… Okay, keep going. Sorry.

Jeff: Do you ascribe to, sort of, the cyclical mindset of things tend to move around, you know, seven-year patterns. I mean, do you put any weight on a timeframe of being down?

Meb: No, but…

Jeff: Or would you look purely at just maybe like when the trend has really changed based upon the 200-day or something like that?

Meb: The longer and deeper the better, because the longer and deeper it is, the more emotional and psychological damage that’s caused all the investors that were involved. Look at Japan. That was two decades of investors that will probably never invest in Japan again, and they went from the biggest bubble we’ve ever seen, to eventually, getting cheap a few years ago, if you remember. Finally got down to really cheap levels, but by that point, nobody wanted Japan. Or just think about the last few years. Think about all the people… When you mention Greece, or Russia, or Brazil people are like “Are you out of your mind?”

So, sometimes it happens on a couple-year, timeframe sometimes it happens even longer. I think commodities has been a great example. We’ve been talking a lot about this year, but even going back to 2016 when we did that article in the first version of the best investment writing, which was, are 50% returns coming from emerging markets and commodities? And pretty rarely does it work out that cleanly, but sure enough, what happened in the next few years, emerging markets went up 50%. And commodities are just now starting to catch hold.

But, talk about an asset class as an example. In mid-2000s, everyone was piling into commodities. Every person on the planet was launching commodity funds, commodities were going through the roof. And then of course, what happened? You had 10 years of horrible performance. And so, it’s, kind of, created this environment where, back to our old sugarud [SP] three criteria, hated, cheap, and starting into an uptrend. So, you had base metals be the first one to go up, and then, energy, precious is kind of lagging. But Ags, which is the one that I always talk about is looks like they’re entering to an uptrend. But that’s…they’ve looked that way a couple times over the past few years.

So the worst that it’s been and the longer it’s been, the more…it’s like a rubber band or a coil. As long as it’s not a tiny industry or single stock, those can go to zero pretty easy, but entire countries, and sectors, and asset classes, that’s a lot more rare.

Jeff: Yeah, but those to me seem like, ironically, the easier investments, the ones that have been down for forever. And if they’re beginning to get an uptrend because it has been so long, I guess I was thinking what about the ones who have been down three, four years, they’re not getting crushed, they’re just underperforming. Do you view those as attractive or are they still kind of… because they’re not at extremes, are you like, “No.”

Meb: We’ll go back to like the old Arnott podcast, where he says “You know, there’s a lot of simple ways to take advantage of this, value investing is one, re-balancing is another one, over re-balancing the concept of moving even more into an asset class that’s really been getting pummelled.” But you can codify all those, right? Like, you can use value funds that will automatically… You know, our largest fund does this. It buys the 12 cheapest countries in the world, so automatically, it does that once a year. And so that is a rules-based strategy, you could do it with your entire portfolio.

So, there’s a number of ways to think about it. You’re an options guy, so you could also say, “Hey, look. Next time that we have an asset class that’s down three years in a row, it’s only happened at this point now six times. The fifth and six were commodities and emerging markets starting in 2016, but may not happen again for a long time. But if it is, you say, “You know what? I’m gonna buy two-year options, leaps.” And you know, if it doesn’t work out, it cost me 1% or something. If it does work out, I make some good money.

But if you do that with sectors or industries, you probably want it to be even deeper and longer, because those are more concentrated. So we used to do those articles where we talked about coal stocks, and uranium stocks, and we didn’t do the update this year, because agriculture I don’t think was down five in a row. But, anyway, so… But those are things… There’s a lot of approaches you could take, and again, shooting from the hip is probably the worst. But you could take ones where you say, “You know what? I’ll over re-balance.” You can take ones or say, “I’ll do small option positions,” or you can say, “I’ll do trend-following approach and buy these when they start to trend.” All those are valid, I think.

Jeff: All right so it just boils down to process, and as I’m sure you will say, it’s not just process, it’s written down process

Meb: And share it with someone, keep you on us.

Jeff: You know what? You’ve just touched on so many questions that were, kind of, perfect segues into some of the write-in Q&A.

Meb: Good.

Jeff: In fact, we missed a few but given that last one about share it with somebody’s I’m gonna jump ahead to the Q&A. We’ll come b4ack to another discussion point. All right, real quick right now, do you suggest that someone have a second opinion on their financial plan much as someone would get a second opinion for major surgery? Even if a client really trust their adviser it just seems prudent to have a second set of eyes look at the plan, thoughts.

Meb: Yeah, why not get a second and third opinion. I mean the challenge there I think is you know, a lot of financial advisers… I guess you could do it on a per-hour-basis, but if you don’t have an adviser and you want one, you should absolutely find one you’re comfortable with. And so there’s no reason not to interview 5, 10 of them and understand their process, understand how they work with people, fees, everything. Because you probably learn more about the profession as well in every meeting to the extent they’ll do proposals, or you can do them per hour where they give you plans absolutely why not.

Because you start to learn particularly for people who haven’t been through it and are kind of uninformed, you probably pick up knowledge in each of those meetings. You say, “Oh well, that guy is kind of full of it because he said xyz,” and the next guy say, “Oh, well, he clearly has conflicts of interest because of this.” But if you just went with your buddy who happen to be your neighbour and was the first one you, probably won’t know those things.

Jeff: I’ll tell you the counter positions to see what you say. All right let’s say you’re getting a coronary bypass. There’s really pretty much one way to fix that, if, you kind, of get creative, you know, chances are it won’t work out well. Let’s say you have two advisers both have very different market approaches. You know, one, is buy and hold long term, one is trend in the more short immediate term.

Their styles could be contradictory at face value, but over the longer term, they’re both gonna do well. So if you get advice from both of them on the same portfolio, one could look at it and say,” This is just a, you know, a piece of crap. The other thinks it’s better and it leaves you kind of stuck in the middle wondering, “What do I do?”s Because it’s not an issue of, it’s right or wrong. It’s potentially just a style differential over different time periods or what not.

Meb: I don’t know if your example is apples to apples. It’s more like apples to oranges, because if you go and get a coronary bypass or not you’re dead or you’re not dead, so I’m not… That example is a little binary, whereas the financial adviser is more like interviewing trainers, where you said, “Okay, this guy’s gonna make me run, and this other guy is gonna make me do weight training. And this third is a holistic approach where they’re gonna focus on diet, but also do yoga.” Like, are all those better than nothing? Yeah, probably. Will they all help? Sure, I’m sure they will.

But are they different styles getting to the same thing? Yeah. A doctor… you know. I think it’s an accurate representation if you said, “Hey I’m gonna get four opinions on, should I have this heart surgery?” and maybe one is a total quack and said, “No, you should go meditate until your heart problems go away.” And that’s probably not gonna work, but the other three said, “Yes, absolutely. You should.'” You know, I don’t know why it would hurt to not interview 10 people to find the 1 that you trust.

And chances are, once you go with someone and go with their methodology and world philosophy and everything else, you’re not gonna…the switching costs are such a pain in the butt. You gotta move…for many of them, move brokerages, switch accounts, there might be taxable events.

Jeff: Yeah, all the more reason to have you know, several interviews if you’re gonna end up getting stuck with one for a while.

Meb: And I think that’s… We’ve mentioned this before as one of the million-dollar investment ideas, there’s still not a good way to go find financial advisers, because the rating systems with the ones they have with like doctors, Zocdoc and all these others, is a financial adviser cannot pay to be on one of these platforms where there’s testimonials. So, a lot of the way these platforms work is they have ratings and they’ll set up appointments for potential financial advisers.

So if you could figure out a way to have a website that would allow for reviews, but it’s even more complicated because the reviews for a lot of people, you know, they may invest or something and not do well, it’s complicated. But there’s no… Listeners, you figure out a good solution, let me know, I’ll invest in it. But, there’s not a good way to find a financial adviser. I mean, you can go to like the FPA website and search for CFPs, but other than that, it’s a lot of word of mouth.

Jeff: How would you do it personally?

Meb: Word of mouth.

Jeff: That’s it.

Meb: But again, I’m in the industry, so I know and have had experience, but it’s complicated.

Jeff: Whatever happened…when you were talking about….you and Jack, you’re gonna sit down with somebody at one point. Did you all ever follow through with that?

Meb: Yeah, it’s confidential. We’re on interview 10 of various…I’m just kidding. Trying to get my house in order. It’s taking a while these sojourns to Greece.

Jeff: All right, let’s hit the last Tweet, and then we’ll go back into the Q&A. You had an interesting Tweet that talked about what matters more, your savings or your return. And it looked at a 10% savings rate with a 6% return, versus a 6% savings rate with a 10% return. You wanna just kind of walk us through what that was? And what you took away from it?

Meb: You know, everyone wants to focus on returns that’s the sexy part, but starting early and particularly saving and living within your means or not, but saving is a huge determinant of portfolio value. And the problem is look, most of us that have lived through our 20s and 30s, you don’t have any money, you’re just like trying not to drown, right? So it’s easy to tell a 20-year-old, “Yeah, just put away 10% of your salary,” when they have a hard time paying their credit card bills.

So, I sympathise with it, but the reality is the earlier you start, the more you save, the better it is. And that’s why having an automated system like 401(k) auto deposit, or whatever it is, where it takes out of your pay check and you don’t even see it is a great way to save, you know, dollar cost average over time. But we’ve done a lot of articles on this general concept where, if you remember back, the “The Best Way to Add Yield to The Portfolio” article, where we showed that unless you have basically 10 million, you should be spending 0 time on asset allocation. And basically spending more time trying to either make a little more money, or invest in yourself. And trying to generate Alpha when you have these low pools of capital is really kind of foolish, versus trying to get a better job or work harder or more.

Jeff: We’ll post this to the show notes, but the chart here that represents the growth curves of the 10% savings and 6% return, versus 6% savings and 10% return. It looks like it’s about 24 years to where they breakeven or so.

Meb: Where the kink happens, and listeners, you can visualise this where savings, or…excuse me. The investment returns really start to matter a lot more post year 20. So if you’re investing for the short term… and this is why if you’re 80 years old, if you need the money and you’re not passing this on to your children, or a foundation, or something, you shouldn’t be 100% in stocks. Because chances are one, they’re super volatile, but it may or may not make a huge difference in your timeframe.

So compounding really works over the long… So, if you look at, for example, media loves touting this with Buffett, where like Buffett is worth this much money, and all of it came in the last 10 years or whatever. You know, he made 90% of his money after he turned 80, but that’s just the power of compounding. So when you make 10% on 50 billion, that’s a lot different than when you make it on 50 million.

So there’s a couple of takeaways. You know, one is that obviously, the numbers of return in savings can vary. So I’m sure there’s a calculator out there that shows you the various graphs and sort of landscapes based on what your expectations for returns and savings may be. But the general rules of thumb, starting as early as you can. I mean, if you remember the episode we did with Merriman where he said he gives his children at birth, whatever it was, $1,000, $10,000, but they don’t get it till they turn 65. So that’s solid 65 years of compounding, which is pretty cool.

Anyway, start early, savings matters a lot the more you can do it. And then returns, of course, help, but the returns are the one you can’t really control. You can’t control the economic climate you were born into, if you were born and started your investing career before the ’80s and ’90s, kudos, you had 2 decades of just straight-up. But if you started investing in late ’90s, you had pretty tough road ahead of you for the next decade.

And so, the biggest thing is you control, which is savings and starting early, and spending your time to invest in yourself, particularly in your 20s and 30s. Can you remember what the Porter rules for investing are? Your 20s are for learning, 30s are for earning, 40s were for investing or something.

Jeff: Fifty giving back [inaudible 00:25:07] that.

Meb: We have to look at the show notes. But I think those are all common sense views.

Jeff: What would you say to…

Meb: People spend way too much time trying to beat the market, that’s for sure.

Jeff: Agreed.

Meb: You just buy our funds and move on.

Jeff: Well, the flipside of that is…are you familiar with the Ramit Sethi?

Meb: Yap.

Jeff: He’s a great entrepreneur and author. He’s written a course “I Will Teach You To Be Rich.” And one of the things I remember from Ramit is he talks about how so many of these “save more” plans talk about, “Well, if you don’t buy that one cappuccino each week, you know, it’s that three and a half bucks, it’ll add up.” His point is like, this is just nickel and diming, plus you want a cappuccino. So he goes for focusing on the big win, so to speak. So how do you balance the need to save more, which obviously is critical, with the reality that saving $1 here, $4 there…

Meb: I agree with almost everything he says there. I agree that…

Jeff: So what’s the best way to save significantly then?

Meb: Well, I mean, look, investing in yourself and that’s easy to say. A lot of people when they’re young they don’t know exactly what that means. But really developing your education or career and working on skills that will propel you to higher salaries matters a lot more in that growth trajectory, than whether you save $10 for…I think he really hates avocado toast or coffee.

Listeners actually pretty funny because “Vice” reached out to us on our advice for young people and graduation if they were to give you $100 for what you should do. One was for something fun, and then two was to invest, so I asked Jeff what he said and we both agreed on number two, which was, of course, investing in one of Cambria’s funds. But, I think we both said our largest fund, which invest in the cheapest stock markets around the world. But the first one had a quite a different response because Jeff said, “Just go buy a bitcoin.” And we deleted that one, by the way, and I said…

Jeff: That would anger some people [inaudible 00:27:04].

Meb: I said, “Take the 100 bucks. Every morning, get up a little earlier, go buy a coffee,” so that’s 5 bucks each, unless you’re in LA and get a single pour over, which I saw one the other day which was $10, a single origin pour over. And, by the way, I actually went and I said, “Can I have a little milk in this?” And she says, “We don’t add milk to our coffee, it’ll probably cuddle, so we ask that you try it without any milk first.”

Jeff: So LA.

Meb: I said, “Okay. It’s okay.” And then I also had a piece of chocolate cake with peanut butter…it was a Japanese coffee shop, peanut butter rice circle in the middle and felt sick for about four hours. And then before going on “Bloomberg,” went to a Chinese restaurant that had peppercorns, the…whatever, the Szechuan peppercorns that make your mouth go numb.

Jeff: You’re spiralling right now.

Meb: If you listened to my interview on “Bloomberg,” it sounds like I’m slurring because, like, my entire face was numb. Anyway. What were we talking about? Oh, yes, so advice. So, I said, “Spend a $100.” So every morning, if you’re a coffee drinker go get a coffee. Wake up 30 minutes earlier, hour earlier and go listen to an episode from one of the top 5 Wall Street Journal rated podcasts, which we happen to be one.

Jeff: Wait. I thought this advice was bad advice.

Meb: No, I said fun…number one was fun…

Jeff: All right.

Meb: …fun or silly.

Jeff: I misinterpreted it. I thought this was sort of like [inaudible 00:28:27].

Meb: And so I said, “Spend 100 bucks each day. Go listen to a podcast, so you can listen to two in an hour, because you’re listening at 2x speed. And so after 20 days, you’ll have listened to 40 hours’ worth of world-class investing ideas.” And I said, “That’s free, so what a great way to get started.” Anyway, I, don’t think anyone’s gonna get to my input on the “Vice” article.

Jeff: All right. Let’s dig into some of these listener questions. All right. So tying back in the commodities here, Meb, what is the best way to include commodities in a portfolio? Specifically, is it better to have an ETF containing futures contracts, or an ETF containing commodities equities?

Meb: They are different, you know. I think if you want true commodity exposure, I think futures is the correct way to do it. I think you need to have reasonable expectations of returns. I think they’ll be probably closer to bonds, but somewhere between bonds and stocks over time. You need to make sure you buy a commodity fund that has, sort of, the 2.0 re-balancing rules. So, a lot of the early commodity funds were pretty “dumb,” sort of, ways to do it. And if you look at what people call the dirty secret of indexing is all the indexes get front run from the S&P and Russell, all the way down to commodity indexes, and these very basic commodity strategies. It was a cost of a couple percentage points per year.

So they’ve updated to where there’s all sorts of different re-balancing methodologies, but being smart about it and having a more thoughtful…but it’s complicated. So if you’re an investor that doesn’t trust that you’ll be able to make that determination, just avoid them. Go buy a gold ETF and be done with it.

Jeff: Do you worry about raw yield issues?

Meb: That’s one determinant and it changes over time too, so you wanna have a fund methodology that tries to be thoughtful about it. But you can also argue that managed futures is a close cousin of long-only commodities, where most managed futures programs are very heavy in commodities futures granted they’ll go long and short. So, you could buy both, or you could buy a fund like one of ours that will concentrate in commodities if and when they’re going up in commodity areas.

So it just depends, but we love commodities, but we’re a rarity as far as investment advisers that have kinda believed in them and stuck with them through this entire past cycle. I like them a lot more now in particular.

Jeff: I’ve seen a lot of…

Meb: Commodity equities they’re more stock like.

Jeff: Define that for the listeners, just real quick, to make sure they know the difference here.

Meb: Stocks.

Jeff: Well, I mean, give an example.

Meb: Well, so, if you buy Exxon or other companies that are in the commodity complex, they have some stock-like exposure and some commodity-like exposure. And it’s more complicated too because some of them hedge, so they may not have the exact exposure to what oil is doing or wheat or whatever.

Jeff: Seems like you’d be getting a lot more insight business risk.

Meb: I would love the farmland ETF some day.

Jeff: You talk about that every time.

Meb: I get emails from all over the world now and people are like, “Well, Meb, there’s this farmland company in Argentina and Russia. Here’s a private fund in the Baltics.”

Jeff: I’ve heard a lot of smart guys say how long-term commodities aren’t really a source of portfolio alpha, they are more of a way to increase your risk-adjusted return. They kinda smooth things out. Do you give that idea any credence?

Meb: Well, I don’t think commodities is Alpha in the first place anyway, the same way I wouldn’t think S&P 500 is Alpha. It’s a beta asset class where you’re getting exposure. Now, I think there’s areas where people misunderstand them. I think that, you know, half the commodity returns, because they use futures, is just a collateral yield of sitting in T-Bills. So when T-Bills are at zero, that is a lot different than when T-Bills are at 5%.

But that applies to every asset class, applies to bonds too, when bonds are at 7%, is different than when bonds are at 1%. But, then the raw yield and the spot return and all that good stuff. I mean, I like them because they diversify and they zig and zag. It would never be a majority of my allocation.

Jeff: Are you going to over re-balance given their valuation right now?

Meb: Well. we do that automatically by the momentum in trend funds, but it’s not based on pure mean reversion.

Jeff: But conceptually, you endorse the idea?

Meb: Yeah.

Jeff: All right let’s move on next question, obviously historical returns from bonds, especially the last 40 years, will not be repeated in the future. How will you position yourself personally, not trinity, but personally, for the bond portion of your portfolio? As a follow up, what are some viable simple options for individual investors, besides having a globally diversified bond portfolio, or is global diversification the answer? Is the global risk somehow less risky than a domestic U.S. bond allocation?

Meb: It’s interesting that he starts the question with “obviously” because I actually don’t think that that’s obvious. If you look at Japan, for example, when their 2-year…when their 10-year bond went below 2%, it hasn’t gone back above since, and this is…I don’t know 10, 20, 30 years now. And it’s been a great investment. Bonds have crushed stocks for a really long time there. By the way, do you know that… Josh Brown Tweeted this the other day and we used to talk about it and just incite people into rage.

Bonds outperform stocks for a quarter of a decade up to the period of like 2009. You know, and most people when they talk about stocks for the long run, that’s pretty damn long time for bonds to be outperforming. And so, you know, yields have been ripping up, but can I foresee a world in which the 10-year goes from 3% back down to 2, 1, 0? Sure. We had negative interest rates in Europe. So talk about an awesome investment. You buy the long bond here and yields go back down to zero. That’s an all-time trade, right? Zero is even better, zero coupon bonds.

So I think everyone always follows the expectation that yields are coming up, and I hear it every day. Fed, QUI, yields gotta go up, inflation, yadda ya. It hasn’t really been the case until about three or four months ago when…or last year, I should say, sorry. Yields have started coming up. So, yes. Do I believe that bond yields are probably gonna hang out where they are now slightly higher in 4% range? Yes. But would I ever bet on that? No. And so, bonds, historically, have been a great diversifier, but it’s not something you can count on. We say that about all asset classes, bonds, in general, I think on average have a positive correlation with stocks, not much. They oscillate all over the place, so it varies, but at various times they are very high correlation and very low.

So, that having been said, I think there’s a role that Treasury is playing in the portfolio that’s distinct from foreign bonds. And foreign bonds you can take the Vanguard approach and hedge them or not, I don’t really care that much. I think it’s sensible for sovereigns. But we wrote a paper on this many years ago about sovereign bonds and said, if you’re gonna do global bonds you may as well…the same way that we say you shouldn’t tilt toward market cap weighted index in the U.S., you may as well tilt to value in which case it’s just carry.

So you buy…and we have a fund that does this, but a high carry global portfolio, it’s gonna yield 5%, 6% right now, which, by the way, the U.S. is almost in the high carry bucket. It’s darn close. If our fund would re-balance now, it would probably be in the high yield category, which is kind of amazing.

But that says more about the rest the world than the U.S. where a lot of the G8, G7 is yielding like 0.5%, on average, where even some, I think, are still negative, but not as much anymore because they weight the bonds by issuance. And so, it’s really kind of a nonsensical approach if you think about it, and historically tilting towards value and global bonds has added additional returns. But, like right now, you end up with a pretty wonky portfolio of Mexican, and Russian, and Brazilian, and probably U.S. bonds and Turkish bonds, which have just been getting pounded. So, it doesn’t have the same role, I think, as U.S. bonds do. So U.S. bonds, to me, are still the core, but foreign bonds are also the largest asset class in the world.

Jeff: I was about to say, if you look at the global market portfolio what are we looking at for bonds? Is it 50%?

Meb: Roughly, I mean, it’s roughly half stocks and bonds, but a portion of that bonds is corporate, so it ends up probably looking more like 60, 40 U.S if you were to count corporate bonds as half stock, half bonds.

Jeff: So, if we could, you know, peel back your head and look inside about your own personal, sort of, you know, projections of where markets are going, would you invest less, would you downsize your allocation from 50%, say to 40%, 35%, whatever, based upon fears of bonds? Or are you like, “No, I don’t have enough reason to worry. I’m gonna keep at it GP 50.”?

Meb: No. I like the John Bogle. He says, “I’m 50-50 stocks-bonds because half the time I spend worrying I have too much in stocks, and half the time I worry that I have too much in bonds.” So bonds, to me, are totally a reasonable asset class.

Jeff: All right. So…

Meb: Despite the fact that no one…going back to our Twitter poll we did, no one understands the risks of bonds. And so if you look at 10-year treasuries historically, we did a Twitter poll and said “How much do you think U.S. bonds, 10-year bonds have declined after inflation over the past century?” And almost everyone said “0 to 10%.” When the reality was is over 50%, over 50% listeners, so that’s because of inflation in particularly the ’60s, and ’70s, you just have this long, gnawing inflation at a time when bond yields were below inflation, which is called financial repression, which we actually have been going through for the past number of years here in the U.S., which we may not be anymore. Now that bond yields are back about 3%-ish, inflation seems to be lower, but that’s called financial repression.

Jeff: All right. Let’s switch to a CAPE question here. Star capital studies in your own book show that 10-year returns of low CAPE Ratio countries are impressive, and get better the lower the CAPE. Still, it doesn’t tell if those returns occur gradually, or if the path to this performance is just noise and cannot be predicted. If the path is noise, it would make sense to buy a cheap country ETF and wait at least 7 to 10 years. But your strategy re-balances every year and doesn’t let your bulls run. Why? Why not hold a longer, 7 to 10 years in total?

Meb: I think is probably fine if you wanted to push the re-balance frequency out to multiple years. I don’t know many people that have that much patience for that. But if you do it any more than yearly it hurts, and even at yearly, there’s not that much turnover. Usually, it’s like one or two countries go in and out, out of a dozen, so that’s index sloth-like behaviour. Now, are there a number of trading rules you could change to that if you wanted to? Sure. You could say, “You know what? I’ll invest in this basket, and if one goes below it’s moving average or above…” Like, there’s a thousand ways to customise strategy to your heart’s content. Way we did it was just pretty simple, but usually, a lot of these countries need to double or triple before they come out of the index. I think Russia’s going to have to triple.

Jeff: I’m not gonna get into the exact details and the methodology, but I’m assuming you buy in a low CAPE and then it’s gonna be in for a while potentiall,y as the CAPE elevates to whatever the higher CAPE metric is that puts that out, so.

Meb: I mean, Ireland was a good example. You know, that we own that in the early days of our fund and it just ripped the face off, and then eventually, you know, you sell it. So, another way to reduce turnover would be to have tolerance bans, which means… So, like, for example, this isn’t CAPE strategy, but, for example, if you invested in a stock in the top quartile of the universe, the top 25%. You say you buy them all in the top 25%, but you only sell it once it drops out the top half, that way you reduce the turnover and you give it a little room to wiggle. A lot of strategies do that to reduce trading cost, not just in ours, but in other ideas and concepts.

Jeff: Next question. I recently read that 88% of companies that were in the S&P during the 1950s are no longer in business. If every company is eventually heading towards zero, why are so few people able to make money on the short side? Shouldn’t the ideal portfolio be long the global market portfolio with tilts to value in momentum and short specific individual equities?

Meb: Shorting is hard. It’s hard for a number of reasons. It’s hard for implementation reasons. You’ve gotta find a borrow, which then you have to pay for. You’re running into the wind because U.S. stocks have historically returned 10% a year. On top of that, shorting requires a lot of portfolio management discipline, because theoretically, you can lose infinite on a short. You can double, triple, quadruple overnight. Whereas if you buy a stock, it usually only goes to zero, although Cheinos [SP] talks about this. People often say your upside is maxed out on a short at 100%. That’s not actually true, because you could continually double down as the stock goes down with more margin and borrowing.

Jeff: Keep thinking about Einhorn.

Meb: What? Which part?

Jeff: Well, I mean, in terms of trying to short a lot of stuff that didn’t work out and then, kind of, doubling down.

Meb: So it’s just hard. Now, as far as the statistics of stocks, you know, you have these big outliers that have the monster returns. So, yes, theoretically if you could come up with a short strategy that avoids those, but it’s just a lot of work. So, to me, here’s the bar. You go sit in bonds and you’re gonna make 3% a year, so can you find stocks to short that after cost of borrowing, after cost transactions, and everything, is gonna be 3% a year? Maybe, it’s just a really hard ball game.

Jeff: What would your personal screen be? If you gotta go short some individual equities…

Meb: I mean, there’s a ton of academic research that will pick terrible stocks, and in general, they under-perform and you could come up with a basket. But you gotta remember, this goes back to Wes’s old articles, said “Even God would get fired as an active manager, because…” Like, let’s say you have that as a traditional portfolio and even if it doesn’t perform, it has periods where they just rip. And this terrible junky basket of stocks will rip up 50%, and you’re dead, you know, so it’s hard.

Now, I love the concept of shorting, I love the personality that gets attracted to shorting. Everyone’s a little crazy. I think that if people can do it right, it’s a huge potential value-add, and lot of people use it as their excuse to charge 2 and 20, a lot of the long/short funds. I’m of the belief that almost none of them earn it or any good at it, so there’s very few that are really truly exceptional. It’s tough.

Jeff: Kinda reminds me of what Montier was talking about on the pod about using leverage in which he said, “That implies that you know something about the path of the mean reversion.” In this case, shorting implies that you , kind of, exactly what’s gonna happen and when. And if you get screwed on that trade, even if you get it right in the long term, if you get a quick volatility to the upside, I mean, you can get really hurt.

Meb: I must have passed out during this episode because I’ve had like six people email me these amazing quotes. I’m like, “He said that? That’s amazing. I don’t remember that. I don’t remember this point at all.” Anyway, all I remembered was “Winnie the Pooh.”

Jeff: You were just tied up on talking about his dress, you loved his Hawaiian shirt.

Meb: And “Deadpool” shoes, keep going, what else do we got?

Jeff: We know stocks are very volatile especially when held for a year or less, but as the holding period increases to 5, 10, 20, 30 or more, the volatility of the stock portfolio decreases, and the returns converge to around 6% annually. Knowing this, why not increase the allocation to an almost 90% to 100% stock portfolio? Buffett is 90% stocks, 10% bonds, people are living much longer and need a stock heavy portfolio.

Meb: I think it’s insane, the reason being not the statistics of it. If you’re Rip Van Winkle and are gonna wake up in 50 years, I think that’s totally fine. Now, granted I would also, again, rather buy a strategy that buys the cheapest stock markets around the world consistently. But what you just mentioned about Wes, the path dependence is because you’re gonna have to sit through a 50% decline at some point, maybe an 80%, maybe a 90%, unlikely. But it happens in many countries around the world.

So, I think Buffett’s advice is actually terrible. I think it’s really terrible advice, because it ignores the fact that people can sit through it. And I just… I don’t… I mean, but Monger says, he’s like “Look, you shouldn’t be investing in stocks or…” He calls them “securities,” “unless you can accept 50% drawdown.” I just think if you diversify, it reduces your odds of that big of a drawdown.

Jeff: All right. We have a question about…

Meb: Sorry, there’s an old… one of the riddles guys either Bartnik [SP] or Ben Carlson or someone where they post a chart of Amazon, and they joked, they’re like, “Look, if you just bought $1,000 of Amazon or Netflix or whatever in 1990, you’d be worth $10 million.” You know, he said, “But also, if you invested $1,000 in Amazon in 1990…” actually I don’t even think they started till like late ’90s, ’99, whatever, “you would also be a psychopath because you would have sat through like multiple 80% declines.” Like no one does that. It’s impossible. It’s really hard.

Jeff: Next question is about the Trinity portfolios. It says, “I’ve looked at your Trinity portfolios and noticed an allocation of 0.88% to a security. Why? Isn’t the impact negligible?”

Meb: Potentially, but you could ask the same question about the S&Ps;, like why allocate to the S&P when the 500, the company is only representing…is 0.01%? So what you’re trying to achieve eventually, is that you have a portfolio that reflects the global market portfolio and you actually own 20,000, 30,000 securities around the world. So you could implement that portfolio with two funds, by the way, so then it’s a question of just granular and tax harvesting, a bunch of other ideas. But yeah, you wanna buy two funds and kinda do it, that’s fine too.

But the question is actually pretty fair in the sense that if you’re doing an allocation with discrete assets, you need to add something with like 5% or larger, otherwise, it’s really hard to make a difference for like a new asset or asset class. But let’s say you had a category where you allocate a long/short equity manager with 10%. Well, is it totally fine to spread that 10% across 10 or 20 managers? Sure. But the whole point being are you adding to long/short equity with 10% or not, it’s a different question.

Jeff: Last question we…

Meb: By the way, we have like a dozen Twitter questions, but my phone died, so we’ll get to them next radio show.

Jeff: It’s time for a new phone. I’ve heard you complaining about that one for a while.

Meb: Yeah, it’s really, really bad.

Jeff: All right using websites like Portfolio Visualizer, backtesting trend following using various moving averages can produce better returns. For example, using an 8-month simple moving average outperformed the 10-month simple moving average for 5 asset classes. So wouldn’t it be better to use the eight-month backtesting moving average? Is this data mining? I think that’s the question, really.

Meb: It’s literally the definition of data mining, you know. When we published our first white paper 2005 2006, we said, “Look…” and we used the 10-month simple moving average. We said, “This doesn’t have the best risk and return statistics for any of them, but it has broad parameters stability, so maybe the eight did best here, and the six did best there, and the 10 did best…

Jeff: Define parameter stability for [inaudible 00:48:38].

Meb: Parameter stability is like if you think of a broad mountain top, not like a Teton’s peak, but kind of like a big plateau, where everything in this general vicinity would work that’s something you want. And you want it to work on as many markets as possible in many different time frames as possible. If you find some strategy that only works in one market and nothing around it works, and it doesn’t work in other markets or time periods, that’s probably data mining. Like, we were joking the other day, we said, “Hey, you know, what works amazing in bitcoin? Seven-day moving average,” and it does, by the way, fantastic way to trade it, but is that gonna work in the future? I’ve no idea. I’m staying away from hoddling. [SP]

Jeff: All right, well that’s it in terms of the Q&A. Anything pressing on your mind? Can you remember any questions that came in that you wanna address before we sign out?

Meb: We’ll save more for radio episode next one.

Jeff: All right. Well, any final sign off before you hit Europe?

Meb: Yeah, guys, summer time. So you guys have any good research ideas, questions, papers, thoughts, send them over. We’ve got some time brewing and some people that wanna work on some new research projects, so fire them over. If you guys have any more questions, we’ll add to the mailbag, feedback@themebfabershow.com. Leave us a review. We love reading them. Check out the new podcast app we’re using which is Breaker.

And otherwise, you can find all the shows, show notes, everything else, at mebfaber.com/podcast. And if you love the show, share with some friends. Take 100 bucks. Go have some coffees. Get an MBA in investing. Thanks for listening friends and good investing.