Earlier this week, I was in line at my local coffee shop. Ahead of me were two young mothers chatting as their toddlers swirled about underfoot.

I couldn’t help but notice as one of the mothers nodded toward her child then told her friend “You know, Billy is already doing some counting and spelling. He’s just SO gifted.” (The names have been changed to protect the innocent. If you live in LA you know this poor child has a random assortment of vowels and consonants mashed together to form a name the world has never seen.)

As the father of a 2-year old, I glanced at Billy to size up the competition…he was licking the display window in front of the pastries.

With all due respect to the mother, my money is on her perhaps being a little biased.

In the investing world, many U.S. investors, commentators, and financial media think that the U.S. is “gifted.” By this, I mean they tend to believe that our stock market is the healthiest and most robust, therefore it warrants a higher valuation than that of other stock markets around the globe.

Is that true? Are we special? Or does the U.S. market “lick the display glass” like everyone else?

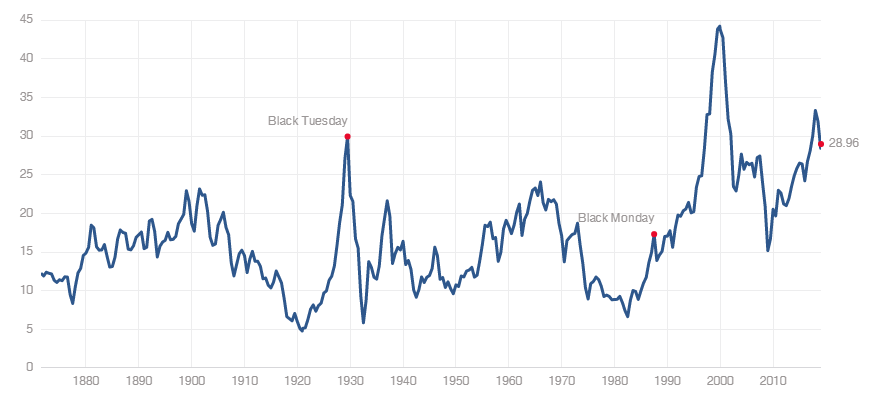

As you can see below, as I write, the U.S. trades at a long-term CAPE ratio of around 29.

Source: Multpl

This level is fairly high from a historical perspective. For further context, the average CAPE from countries around the globe is roughly 16. That makes the U.S. level nearly double that of the average global country. Is that normal?

Many pundits will list the myriad reasons why the U.S. deserves its lofty valuation, rule of law, GAAP earnings, stable goverment (ha!) etc., but a quick look at history cast doubt on the explanations…

First, if the U.S. is truly “special” it should always be special, right? Meaning, if the U.S. market is so fantastic that a higher valuation is always warranted, then historically, it should always have a higher valuation.

But that’s not what history tells us.

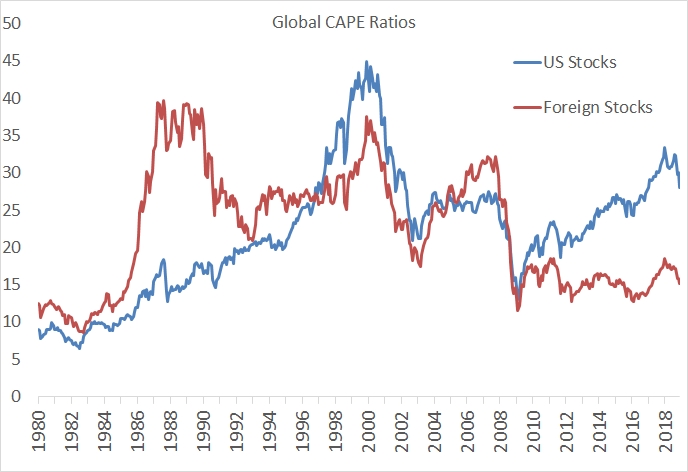

Below is a chart showing the U.S.’s CAPE versus the world ex U.S. (i.e. foreign stocks). Going back to 1980, both have an average CAPE ratio of about 22. Let me repeat: the historical valuation premium has been ZERO.

Beyond that, the amount of time each spends being more expensive than the other is basically a coin flip. That stat surprises a lot of people who assume that the U.S., being currently expensive, ALWAYS trades at a premium and for some reason “deserves to”. (After all, the U.S. is special.)

Source: Global Financial Data

Looking above, you can see that foreign stocks were more expensive during most of the 1980s (due to the massive Japan bubble), whereas the U.S. has been more expensive during the internet bubble and the recent post-GFC.

Today marks one of widest valuation spreads in history, with foreign markets trading at much cheaper levels than that of the U.S.

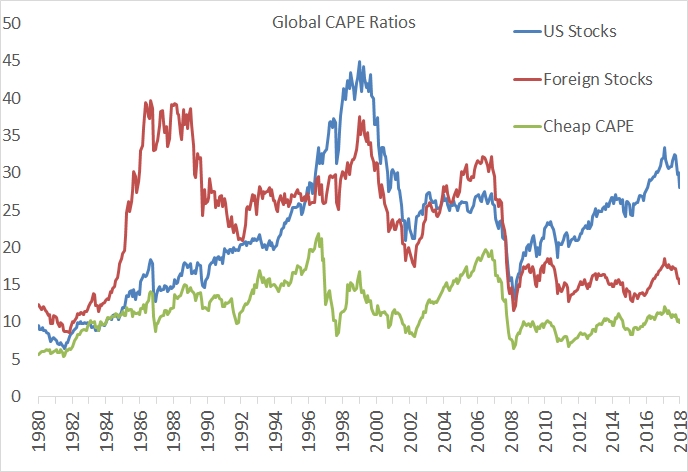

This spread only intensifies if we zero in on the cheapest quartile of countries around the globe. They’re trading at a CAPE ratio of about 11 – that’s a whopping 62% lower than the U.S.!

Source: Global Financial Data

As I pointed out in my post, “You Would Have Missed 780% In Gains Using The CAPE Ratio, And That’s A Good Thing” low starting CAPE values tend to lead to higher future returns 10 years later (compared to high starting CAPE values, which tend to result in lower returns 10 years later).

As you examine your portfolio here at the start of 2019, how much is allocated to the U.S.? Given the historical context above, is your chosen allocation percentage warranted?

I recently polled my Twitter followers, asking for their allocation to U.S. versus non-U.S. It turns out 84% allocate more to the U.S. than to a basic passive index. That’s a pretty big bet on valuations never reverting. Are you willing to make that bet?

(The below is just a twitter screenshot)

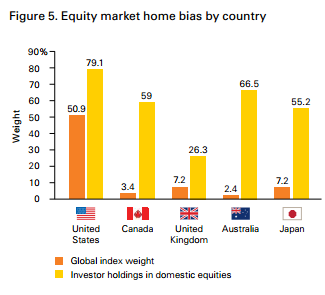

But the funny thing is that every country around the world has this same home country bias. Every investor thinks their own country is special, and allocates more than the passive index suggests.

Source: Vanguard

So, everyone thinks they’re special. It’s hard to be objective about something your are emotionally connected to. Which is why is it so important to be asset class and location agnostic. As you look around the world with an eye to valuation, ask yourself:

Is the U.S. really that special? Or are you really just licking the glass?

P.S. After a fair amount of requests from readers, listeners, and co-workers, I’ve (slowly) started the arduous task of updating my old 2014 book Global Value. (Free download here.)

Look for it to contain updates on global CAPE valuations like the ones identified in this article. It’ll likely be out later this spring.