How to Narrow the Wealth and Income Gap

As a preface to this article, let me say that this piece tackles complex and nuanced ideas about capitalism, its benefits and its drawbacks. I recognize that there are no simple answers, and that many of the challenges touch on deeper questions about class, race, and historical injustice.

That being said, if we are ever to move past the diagnosis of the problems and begin to confront the challenges of capitalism with real solutions, we must start by proposing ideas—however far-fetched or wild they may seem initially. Only then can we hold them up to scrutiny. Only then can we begin to redress some of the tangible, urgent, and everyday problems that real Americans face as they try to live their lives, provide for their families, and secure their futures.

This is my attempt to throw ideas at the wall and see what sticks. These are cursory, very loosely sketched concepts. But they’ve been circling in my mind for a while, and I’m interested to see whether they resonate or not.

OK, then. Where do we start? We start with the beast in the room.

So, just how bad is the wealth and income gap?

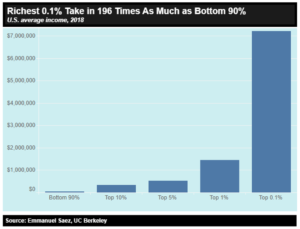

According to Inequality.org, the richest 0.1% of Americans earn nearly 200-times as much as the bottom 90% of Americans.

If that doesn’t grab your attention, try this one on…

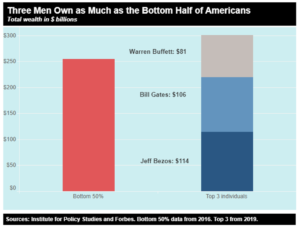

Also according to Inequality.org, the collective wealth of just three individuals – Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, and Jeff Bezos – is equal to more than the collective wealth of the bottom 50% of all Americans.

Now, let me pause here.

This is not yet another piece railing against the unfairness of the wealth and income gap while offering no actionable solutions.

Today, instead, we’ll discuss practical steps to address the problems.

Now, a quick question before we dive in…

Why should you even want to have this conversation?

Well, two reasons – one, to include and share the benefits of capitalism with everyone; and two, to preserve this capitalist system that may have its flaws, but it ultimately beneficial to all of humanity in myriad ways.

As staggering wealth-disparity headlines fill the news, and people look around for answers, capitalism receives much of the blame. But before we move too quickly to throw it out lock, stock, and barrel, it is important to remind ourselves of the very real benefits of this system: the dramatic rise in human living standards over the last 200 years.

While it may seem reductive, the simplest way to understand that link between capitalism and the tangible rise in living standards is that capitalism leads to growth – both economic and innovative growth—and this basic fact transforms our lives.

Michael Strain, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, put it this way in an article for the Washington Post a few years ago:

Imagine the world in the year 1900 — a world without: air travel. Skype. Wikipedia. Google. Smartphones. High school. “Star Wars.” Amazon Prime. Modern air conditioning. Antibiotics. “The Big Bang Theory.” Springsteen concerts.

None of these existed then. What in the world of tomorrow does not exist today? We need growth to find out.

Over the past two centuries, growth has increased living standards in the West unimaginably quickly.

Many more babies survive to adulthood. Many more adults survive to old age. Many more people can be fed, clothed and housed. Much of the world enjoys significant quantities of leisure time. Much of the world can carve out decades of their lives for education, skill development and the moral formation and enlightenment that come with it.

Growth has enabled this. Let’s keep growing.

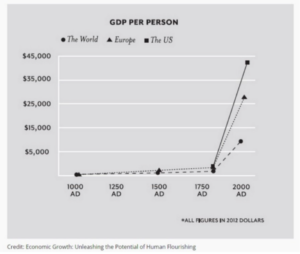

Speaking of growth, look at the chart below showing GDP per person across the world, Europe, and the U.S.

The chart covers from 1,000 AD through the modern day. There is a massive spike in GPD per person around 1800, which is ballpark when capitalism began to flourish.

Coincidence? You can read more about the history of capitalism in the great books Americana and The Birth of Plenty, and the future in Abundance. It’s impossible not to be optimistic about humanity’s progress and capitalism’s role in it.

Let’s return to Michael Strain:

Economic growth is the most effective tool for lifting people out of utter destitution in human history. This is true to this very day, and it is no small thing; it should not be treated and dismissed as a small thing.

The poor are still with us, both here and abroad. They deserve a robustly growing American economy and the benefits that come with it.

Strain’s comments lead us to the second reason why you should care about this wealth-gap conversation –capitalism’s benefits haven’t been working for everyone. And in recent years, this disparity has revealed itself to be untenable and grossly damaging.

A tremendous amount of capitalism’s wealth has flowed toward a tiny group of individuals. Now, this feature is partially by design, the best ideas and creative destruction of the marketplace rewards the winners. But it often leaves behind many, too.

Not only is this limited-benefit version of capitalism socially and ethically problematic, it is also economically unsustainable in the long-term.

Fellow investor, Ray Dalio of Bridgewater, has talked about this:

…capitalism is a fabulous way of creating incentives and innovation and of allocating resources to create productivity. All successful countries have uses for it…

But capitalism also produces large wealth gaps that produce opportunity gaps, which threaten the system in the ways we are seeing now.

After providing examples of the wealth gaps and how they impact opportunity, Dalio points toward the takeaway which everyone should be concerned about:

…the have-nots want to tear down the capitalist system at a time of bad economic conditions.

That dynamic has always existed in history and it’s happening now.

As Dalio sees it, capitalism is wonderful. It’s also the best, most viable way to lift the “have-nots,” out of poverty. But if we don’t make it work for everyone, then it does not ultimately work. Those who are economically marginalized will turn their righteous anger against the very system that stands the best chance of uplifting them.

So, today, let’s discuss some practical solutions to address the wealth gap so that everyone benefits from the spoils of capitalism.

- Teach money in school, starting early

Did you know that most high schools don’t teach students anything about money or personal finance?

Yet, we expect a 17-year old to make major life decisions, like taking on hundreds of thousands of dollars in student debt for college.

We have certain classes that are required for high school graduation (including, some abstract classes like Calculus or Latin), but nothing about the single most important skill they will use on a daily basis for the rest of their lives.

From the National Financial Educators Council:

While today’s youth struggles with their finances and dig themselves into monetary holes that might affect their entire lives, we are in desperate need of a quick, effective solution.

Youth financial literacy statistics highlight the problem and point to solutions.

Parents need to talk more openly with their kids about money and schools need to make financial education part of their curriculum. Teachers need to become more confident in teaching finances to kids and stakeholders in public financial literacy programs for today’s youth need to be accountable for the results they get.

Only then will we be on the way to financial security.

Granted, a lot of parents are not much better with money either. So, let’s start teaching kids about money in school – and let’s start it early.

And no, I’m not talking about “stock picking contests” either. I’m talking the blocking and tackling of basic fiscal responsibility…

Saving money… Living within your means… The power of investing and compounding… Can you afford to buy a home? … The concept of opportunity cost…

Most importantly, don’t call it “Personal Finance” (zzZZZzz), but instead, something that includes the benefit of learning the information…

Maybe: “Money and Your Freedom” or “Wealth and Happiness” or even “How to Get and Stay Rich.”

The curriculum could profile lots of our greatest entrepreneurs and investors in a way that celebrates them, but also makes it feel relatable. Demonstrate a path where everyone can become rich.

Point is, frame it in a way that makes sense to students and makes the content valuable.

On that note, I’m hopeful we can introduce these concepts into our public education curriculum, but I’m also a realist when it comes to our governments.

Startup ideas that I still believe there is massive opportunity for include the “Rosetta Stone for Investing” or the “MasterClass for Investing.”

Did you know that out of all the classes offer in the popular “MasterClass” series, there are zero on investing?! People want and crave this info, after all Dave Ramsey does over $100mm in revenue every year.

Wrapping up this first point – teach money skills early, teach often, and keep teaching. And make it mandatory for high school graduation.

- The Freedom Dividend

Universal Basic Income (UBI).

Below is how Andrew Yang defines it.

I’m giving Yang the spotlight because he drew a great deal of attention to the idea when he made it a platform in his bid for the democratic presidential nomination last year.

From Yang:

… (a universal basic income is) for all American adults, no strings attached – a foundation on which a stable, prosperous, and just society can be built.

Yang’s manifestation of the idea would allocate $1,000 per month to all Americans, no questions asked.

It’s a polarizing concept.

On one hand, there is a groundswell of support for it.

On the other hand, there is legitimate fear of Socialism and Communism, and this kind of government subsidy seems to blur the lines for people. So, in addition to whatever other logistical and other challenges there may be to it, there’s also a substantial marketing problem with the idea.

Plus, for many, the idea of giving people “free” money conflicts with foundational American values of thrift, enterprise, and hard work. For those who oppose it, UBI becomes synonymous with sloth and unearned handouts.

Yet, various studies suggest that this kind of financial safety net could break the cycle of poverty, decrease certain crimes, and allow many to at least “get by”.

For these reasons, a Universal Basic Income deserves serious consideration. The question is, are there ways to reframe it that might make it more compelling to skeptics?

For starters, instead of UBI (which sounds like a medical problem) let’s use the term, the “Freedom Dividend.”

And instead of it being a gift that just gets spent, let’s include a requirement that this money be invested. Perhaps a 50/50 allocation of stocks and bonds where the monthly income would be tied to the growth of that account. That way recipients can see the principal grow over time.

In this current inequitable environment, the stock market has become emblematic of everything that is wrong with a capitalist system. But if some version of a Universal Basic Income was tied to the growth of the market, its success would be beneficial to all. For once, we may all find ourselves cheering for American businesses and its investment markets to succeed rather than demonizing them.

We hardly have this team spirit today. Right now, if Amazon hits a $2 trillion market cap, only shareholders benefit, which is a minority of citizens.

And Amazon isn’t an outlier. That’s because 84% of stocks are owned by the wealthiest 10% of American households. And over half of all Americans own zero stocks.

This needs to change.

If ALL Americans own stocks, it will help address the toxic “us versus them” socioeconomic dynamic that does not lead to productive solutions, only fragments us further.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau quipped about the French Revolution, “When the people shall have nothing more to eat, they will eat the rich.” The current, popularized version that’s gaining traction is simply “Eat the rich.”

This is a clarion call to pay attention. If you think the wealth-gap isn’t your problem, you are wrong. The indignation of the hungry is everyone’s problem, as Rousseau reminds us.

Consider how different things would look if all our fortunes were tied together.

Back in September, former US Labor Secretary Robert Reich tried to vilify Elon Musk, tweeting:

“Tesla forced all workers to take a 10 percent pay cut from mid-April until July. In the same period, Tesla stock skyrocketed and CEO Elon Musk’s net worth quadrupled from $25 billion to over $100 billion. Musk is a modern-day robber baron.”

Musk’s response aligned with the idea of the Freedom Dividend:

“All Tesla workers also get stock, so their compensation increased proportionately. You are a modern day moron.”

Bottom-line, when we’re all on the same team, we share in the same victories.

Another idea related to the Freedom Dividend would be to grant all children in the U.S. a “baby bond” of say, $10,000. If invested in stocks that return about 10%, that $10k grows to about a million bucks at retirement.

It would be invested in a similar manner, and only available for use at a certain age. (Lots of permutations here).

The main takeaway to this point: we want everyone to be investors and to benefit from capitalism!

On this reconsidered model, the Freedom Dividend is a common investment that puts us all on the same team, creating financial camaraderie and a shared reason to cheer.

(Note: A somewhat related idea from Joel Greenblatt is the concept of raising the minimum wage to $15, but having the government cover the spread at rates over $7.)

- Universal Retirement: Copy Australia.

Australia has the best pension fund system in the world. That’s my opinion, at least. I’m a big believer that you don’t have to invent the best systems in the world, but it’s perfectly OK to copy others with better ideas. Here’s what Charlie Munger has to say:

“I believe in the discipline of mastering the best that other people have ever figured out. I don’t believe in just sitting there and trying to dream it up all yourself. Nobody’s that smart.”

The nice feature of the Aussie system is that it’s also rooted in the best learnings of behavioral science.

So, what is this amazing system? Certainly, to be so effective, it must involve some complicated algorithms and brain-numbing calculations, right?

Not so much.

Here’s MarketWatch, explaining:

Superannuation accounts are similar to the U.S.’s 401(k) plans, but the Australian government mandates employers contribute to them.

Each year, private-sector employers must put the equivalent of 9.5% of their employees’ salaries into these accounts, out of the employer’s own assets and not the wages of their workers.

Employees can then voluntarily contribute their own earnings to the account.

The employer’s contribution will gradually increase to 12% by 2025.

There’s a government-benefits part of it too, but the mandatory savings account, financed by employers, is huge.

It’s not a perfect system (it’s beyond the scope of this piece to dive into all the pros and cons). But let’s compare the shape of the average Australian retiree with the average U.S. retiree to see the difference it makes.

MarketWatch goes on to note that the average Australian approaches retirement with $300,000 in his superannuation accounts.

Meanwhile, Personal Capital has highlighted that here in the U.S., the average retirement account is about half of that, and Ben Carlson’s new book has even more dour statistics.

Worse, advisors often recommend saving 5-10 times annual income, but almost 40 million households have no retirement savings at all!

Edward Jones found in a survey that 51% percent of individuals are not actively contributing to a 401(k) plan. Meanwhile, only 37% are contributing to an individual retirement account (IRA) and 18% to a health savings account (HSA).

So, how might we fix this here in the U.S.?

Well, let’s borrow from Nobel economics prize-winner, Richard Thaler. He’s the man behind “nudge theory.”

Here’s the Independent describing this idea:

(A nudge) encourages people to make decisions that are in their broad self-interest.

It’s not about penalising people financially if they don’t act in certain way.

It’s about making it easier for them to make a certain decision.

“By knowing how people think, we can make it easier for them to choose what is best for them, their families and society,” wrote Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in their book Nudge, which was published in 2008…

The Independent then goes on to illustrate the nudge principle in practice, applied to the UK pension system:

In order to increase worryingly low pension saving rates among private sector workers the Government mandated employers to establish an “automatic enrolment” scheme in 2012.

This meant that workers would be automatically placed into a firm’s scheme, and contributions would be deducted from their pay packet, unless they formally requested to be exempted.

The theory was that many people actually wanted to put more money aside for retirement but they were put off from doing so by the need to make what they feared would be complicated decisions.

So, did it work?

It did. Incredibly well.

The Independent article highlights how, since auto enrollment was introduced in 2012, active membership in private pensions jumped from 2.7 million to 7.7 million in 2016.

Why not introduce some version of this here in the U.S.?

We need it. The U.S. system is too damn complicated with 401ks, IRAs, Roth IRAs, SEP IRAs, HSAs… It’s no wonder people don’t save.

Let’s introduce a system that increases simplicity and requires opting out, rather than opting in. That would remove the scariness and confusion of the sign-up process, so that not signing up wouldn’t hurt people financially.

In essence, make it simple and make it mandatory.

Again, follow the Australians. Over there, the funds are called “Supers,” and if you talk to the locals, they love their system.

That’s an effective system combined with effective branding.

Why can’t we have that here?

- Savings Based Lottery

As we have just seen, Americans are terrible savers.

Here’s ABC News with those details:

Almost 40% of American adults wouldn’t be able to cover a $400 emergency with cash, savings or a credit-card charge that they could quickly pay off, a Federal Reserve survey finds.

About 27% of those surveyed would need to borrow the money or sell something to come up with the $400 and an additional 12% would not be able to cover it at all…

Now, this seems odd to me, since a separate report from Bloomberg finds that the lowest-income households in the U.S. spend – on average – $412 on lottery tickets every year.

Supporters will claim lottery engagement is voluntary, but we all know it’s extremely predatory. Any politician worth their salt would ban the lottery in its current form. Of course, they won’t because cash-strapped municipalities are addicted to the tax revenue.

Unfortunately, this is a tax on those who can least afford to be taxed.

So, how might we improve this?

Well, some countries have variants of the lottery where a portion of the ticket-revenue goes into a savings account.

A related idea is a savings account that offers a lottery-like giveaway.

The concept is called “prize-linked savings.”

In short, it’s basically just a savings account in which you’re incentivized to put more money into your savings account.

The incentive comes in the form lottery-ish cash payouts. Of course, unlike a lottery, even if you lose, you’ll keep your original principal.

While not popular yet in the United States, a few companies are tackling the opportunity like Yotta Savings and Long Game.

Here’s how it works with Yotta:

Every $25 saved gets you a recurring ticket into weekly number draws.

And that lottery payday?

It pays out up to a max prize of $10 million every week!

I liked this idea so much I invested in the company. If you use the code “MEB” at signup, you’ll receive 100 extra tickets.

I won $0.10 in my first week, but you can find plenty of people on the leaderboard that have won $1,000 or $5,000!

My twist on all this would be that the deposits are invested in a portfolio that ties back into your retirement account or a long-term annuity account.

Wrapping Up

Capitalism is an extraordinary system that has, quite literally, transformed the quality of human life over the last few hundred years.

But like all economic systems, capitalism can be abused, or fall out of balance. And in recent years, we’ve seen such this imbalance go off the rails.

But with some focused action steps, we can address this imbalance so that capitalism does a better job of benefiting everyone.

Today, we only began to scratch the surface on potential steps. And the thing is, nothing we talked about was rocket science.

We covered basic education about money and capitalistic principles, simple public policy changes, and some innovative, rewards-based private sector solutions.

I offer none of these as “the” way to fix the system – they’re merely potential ways. There are countless other ideas.

But the commonality across all ideas is one thing…

Action.

Unfortunately, right now, this seems to be the missing ingredient since too many pundits remain in the talkative “complain about it” stage.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

You just read a handful of my ideas. If you have your own easily-actionable ideas, send them my way. Or if you have a smart friend who you believe has an idea, forward him/her this article and ask if they’re willing to share their thoughts with me.

If we get enough responses, we’ll compile them, update this article, and cross fingers one of our public officials, or a deep-pocketed investor likes what he/she reads and takes action.

Send them my way at mf@cambriainvestments.com

Good investing,

Meb