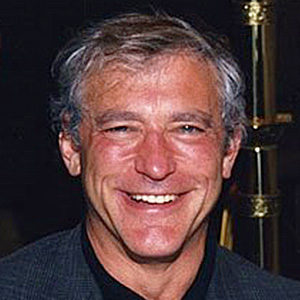

Episode #306: Jeff Seder, EQB, “We Ended Up The First Triple Crown Winner In 37 Years”

Guest: Jeffrey Seder founded EQB, Inc. (Equine Biomechanics and Exercise Physiology), a high-tech sports medicine startup, in 1978 after working as a groom in racehorse barns and breeding farms and then managing a race horse training center and racing stable. EQB is a consultant to the majority of the top ten major thoroughbred racehorse racing stables. A graduate of Harvard, Harvard Law, and Harvard Business School, Jeffrey Seder worked for Citicorp’s International Banking Division in New York City.

Date Recorded: 4/21/2021 | Run-Time: 51:20

Summary: In today’s episode, we hear the best moneyball story you’ve never heard. With the Kentucky Derby this weekend, there’s no one better to listen to than Jeff, who’s disrupted the horse racing industry with his quantitative approach. He walks us through all he’s gone through to gather data over the last 30 years and why the industry has been resistant to data even to this day.

Then he explains why studying the size of one ventricle in a horse’s heart led him to believe the it had the potential for greatness, leading him to tell his boss, “Sell your house, don’t sell this horse.” Not a bad call since that horse, American Pharoah, went on to become the first Triple Crown winner in 37 years!

As we wind down, we hear what Jeff thinks about this weekend’s Kentucky Derby and his advice if you’re thinking of betting on the race.

Sponsor: URNM: The NORTH SHORE GLOBAL URANIUM MINING ETF is made up of a basket of companies that are involved in the mining, exploration, development and production of uranium as well as companies that hold physical uranium, uranium royalties or other non-mining assets.

Comments or suggestions? Email us Feedback@TheMebFaberShow.com or call us to leave a voicemail at 323 834 9159

Interested in sponsoring an episode? Email Justin at jb@cambriainvestments.com

Links from the Episode:

- 0:48 – Intro

- 1:49 – Welcome to our guest, Jeff Seder

- 2:20 – How Jeff transitioned from attending Harvard to working with horses

- 5:52 – Joining forces with the United States sports medicine committee

- 9:38 – Starting out by hiding in the bushes to gather horse race data

- 12:03 – Early days of talking to trainers and buyers

- 17:26 – Developing testing methods to accurately measure race horses hearts

- 20:05 – Direct measurements of horse bone density mailing horse legs to MIT

- 22:48 – Sponsor: URNM: The NORTH SHORE GLOBAL URANIUM MINING ETF

- 24:14 – Other insights that do or do not contribute to a horses success

- 27:58 – The onramp of Jeff disclosing his new discoveries with everyone else

- 29:37 – The American Pharaoh story

- 31:59 – How the pricing of race horses works

- 36:32 – Is there a correlation between heart size and a winning horse?

- 38:38 – What is on the horizon for Jeff and his industry

- 41:18 – Are winning metrics more important than training?

- 44:34 – How the field looks for the Kentucky derby this year

- 45:58 – Which horse was Jeff’s most memorable across his career

- 48:06 – How big of a role or influence does gambling have on horse races

- 50:25 – Learn more about Jeff; eqb.com

Transcript of Episode 306:

Sponsor Message: Today’s show was made possible by the North Shore Global Uranium Mining ETF, ticker symbol URNM, a focus play on miners and holders of uranium.

Welcome Message: Welcome to “The Meb Faber Show” where the focus is on helping you grow and preserve your wealth. Join us as we discuss the craft of investing and uncover new and profitable ideas, all to help you grow wealthier and wiser. Better investing starts here.

Disclaimer: Meb Faber is the co-founder and chief investment officer at Cambria Investment Management. Due to industry regulations, he will not discuss any of Cambria’s funds on this podcast. All opinions expressed by podcast participants are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of Cambria Investment Management or its affiliates. For more information, visit cambriainvestments.com.

Meb: What’s up, friends? We have a phenomenal show for you today where we’re talking the ponies. Our guest is the founder of EQB, a high tech sports analytics company that consults with the majority of the major thoroughbred racehorse stables. Today’s episode we hear the best Moneyball story you’ve never heard. With the Kentucky Derby this weekend, there’s no one better to listen to than our guest who’s disrupted the horse racing industry with his quantitative approach. He walks us through all he’s gone through to gather data over the last 30 years and why the industry is still resistant to this day. He then explains why studying the size of a ventricle in a horse’s heart led him to believe that it had the potential for greatness, leading him to tell his boss, “Sell your house, just don’t sell this horse.” Not a bad call since the horse was American Pharoah, who went on to become the first Triple Crown winner in 37 years. As we wind down, we hear what our guest thinks about the weekend’s Kentucky Derby and his advice if you’re thinking of betting on the race and boxing up that exacta. Please enjoy this episode with EQB’s Jeff Seder.

Jeff: Very nice to be here. Thank you.

Meb: Jeff, welcome to the show.

Jeff: Today I am in…

Meb: Where in the world can we find you today?

Jeff: Southern Pennsylvania between Lancaster and Philadelphia on a horse farm. And it’s a beautiful spring day.

Meb: I miss springtime in the East Coast. I’m a West Coaster now, but spring is as good as it gets. So, we’re going to get all things horses for a minute. And I want to hear your origin story on when you started to get into horses. But you have a pretty cool background. I mean, we’re talking Harvard MBA, Peace Corps, bobsleds, all sorts of crazy stuff. Give me the quick origin story on how a guy with that sort of background gets into horses.

Jeff: I took a ride one day in May when I was 26 at a rental stable on a date. And instead of falling in love with a girl, I fell in love with a horse. And I started doing everything horse and became obsessed. And then it was May…not May. It was probably March or something, in my senior year, I was in the Harvard JD/MBA program and I had to do a thesis that was a combination of business and law. And my thesis advisor was Archibald Cox, from the massacre, the Nixon thing, the investigator, independent counselor, a famous guy. And I went into his office and he was in the stacks, which is the stacks are all just stacks of books everywhere in the belly of a library somewhere. And I sat down, and he said, “Well, how’s it going?” Well, I had to admit I really hadn’t done much of anything. I thought he would throw me out. And he says, “Well, what are you interested in?” And I looked down at the floor and I said “Horses.” And I thought that would kill it, but it didn’t.

And so he turned around and he pulled up enormous book off the shelf behind him, drops it on the desk, and the dust goes up all over the place. And he says, “This is the Massachusetts statute that governs horse racing. I don’t think anybody at Harvard has ever looked at it. Why don’t you do that?” So I did and I became wild. I went to the statehouse in Boston, I looked up things about the racetracks, finances, and the law, and everything else and I ended up getting an A on it. And I wanted to find a career with horses where I might be able to actually earn some money, so I decided that would be in racing. The more I learned, I realized that horse racing was really done the way it had been done for, like, 300 years ago. There was no modern management at the tracks or in the stables. There was no real modern stuff in the selection or the management of the horses by trainers. Most of the stuff about pedigree was just garbage statistics, just garbage methodology.

And I said, “Well, I’m computer literate. We’ll just start with computers.” And I was working with a huge computer with punch cards and programming in FORTRAN. And I said, “But I know something about statistics and I got an MBA. I can make a contribution here.” And not only that, but it was… So, I started doing that. And then in 1976, the East Germans burst on the scene. The Olympics had always been a competition between Russia and the United States, who can win the most medals. All of a sudden, this little country was skunking us both and it was a big surprise. And there were rumors that they were doing it with mad scientists in the basement with five-year-olds that had been there for a decade and turned out mostly it was steroids and other crap.

But anyway, the United States decided they needed a reaction. So, I remember the coaches banded together and it became what is now the United States Olympic sports medicine committee. And I was one of the founding people because I was involved with some of the coaches and I was called in as a young lawyer to help them get a nonprofit status, because they said they would help people who were trying to help the Olympics with the tax law. So, I was too young to realize that it would trigger people like Nike and other people never paying taxes ever again claiming everything was for the Olympic research. But I actually got it done. I think I was the only one and then they slammed that loophole shut.

And so then we had a foundation, which ended up breaking away. I ended up doing half of the biomechanics work attached at the hip to the guy who was the head of the biomechanics division of United States Olympic sports medicine committee, Dr. David Barlow, a terrific guy. And we went to the bobsled, and the fencing, and figure skating, and had special cameras, and all kinds of computer and digitize and everything. I was a big education. And we made a big difference. The bobsled people before we got involved had never been in the medal contention. And after that, they were. They bought $1 million sled, they thought that would make the difference, but it didn’t. What made the difference, we went up and we filmed at Lake Placid at the World Championships. What we did, we benchmarked the perennial champions who were the Scandinavians, and the Germans, and the East Germans, and the Swedish, and things like that, and the Swiss. And we found out that it was how they pushed the sled. We were recruiting like football players to push our sled, but they were more or less recruiting people like ballet dancers. They were so coordinated, the outside leg, the inside leg of both guys. The sled didn’t wobble at all. And that little wobble at the start, by the time you get down to the bottom of the hill it was slowing you down, it was a lot of friction. And it was a big deal how you push the sled, the way they did that, not the sheer power, but the smoothness of it. To do that, we had to set up the camera at the top of the hill. And the East German coach knew what I was doing and he didn’t want us to do it, so he stood in front of my camera. So I politely asked him to move. And each time when they would get there, he would stand in front. So, finally, I just had to push him aside. And then he got pushed back. Well, I was an Olympic trials level wrestler. I didn’t need any shit from him, but I just basically had him down the hill and went on and got our film done. And it was an eventful trip.

Meb: And when you say film, I mean…

Jeff: No, no. This was a low cam…

Meb: …this wasn’t like an iPhone film, like…

Jeff: …the specialized cam…

Meb: It was probably some…?

Jeff: …with specialized film, it went 500 pictures a second. It was all film. The video cameras were over $100,000 doing what an iPhone would do now. So, it was a big rigmarole to get that data and to analyze it, but we did it.

Meb: And so, did you ever take a turn behind the wheel and head down the track?

Jeff: No. I learned to ride…

Meb: It seems horrifying to me.

Jeff: …also a motorcycle…I had a motorcycle racing license from production 600ccs. And riding a racehorse felt faster. It was scary. While we were in Lake Placid, we took a plaster horse, statue of a horse and put it in their wind tunnel and study stuff about the horse and the jockey and stuff. Anyway. So, I got into it that way. And I attached myself to Barlow and the Olympic thing, and then there was a guy at MIT, George Pratt, who was an electrical engineer who was really interested in horses. And he was doing high-speed photography at the gate and writing about it. And so I went and worked with him and helped him. And that’s kind of the launch of the thing. And now it’s 35 years later and millions of dollars of private research and huge databases. A lot of work.

Meb: And so, what was the sort of origin story? Was it you deciding to go out on your own? Was it in the early days realize, “Look, I probably couldn’t be a jockey?”

Jeff: I was too big to be a jockey, I didn’t have the connections, I didn’t have the money. So, I said, “If I’m going to do something in horse racing, I think it’s, I’m going to help them with management and science because they’re really…” The pedigree stuff, if we get into the statistical thing of what I’m doing and how I do the quant, I get to talk about pedigree and I’ll make an enemy of all the traditional horsemen when you hear that. But it’s true.

Meb: Good. That sounds like this podcast. So, how does one get started back then? I imagine there weren’t really that many organizations out there where you could say, “Hey, let me come and apprentice or intern,” or ?

Jeff: No, it wasn’t. I had hide in the courses at the world championships with my camera…

Meb: …your own thing?

Jeff: …on the backstretch of filming horses and go and talk to the trainers and I would go and talk to a famous trainer at the time, it was Leroy Jolly. He listen for like five minutes, he said, “I don’t need that. I know it all literally.” And I thought, “Oh, God.” And that’s what I was up against. And then we got all kinds of surprises. And of course, a lot of times the surprises are not what the traditional people want to hear. And some of it is not so surprising, but they don’t want to hear it the way you say it. The Olympic riders, they would talk about balancing the horse on the bit as physics, that’s ridiculous. They were experts. They were winning. They were doing something. So, I had to figure out what the hell does balancing the horse in the bit mean, because it sure as hell isn’t the center of gravity of the horse. So, it was a lot of work.

And then we would go back and show it to them and they didn’t know what to do with it and a lot of them didn’t want to hear it or they didn’t have time. And nobody would pay for it. It all came out of my own pocket. I had to have a day job. I came out of JD/MBA. And I have been in African with the Peace Corps and I was really interested in developing countries. So, I went to Citicorp. In those days, the international banking group of Citicorp was, that was it for international banking in developing countries. But I wasn’t really happy there. And I went one day to have lunch in their new building at Lexington and 52nd or something. It had this huge atrium where it was the lunchroom, which were like three or four stories high. And all around on the walls was this huge mural of Pennsylvania farmland. And I was looking at it and thinking, “Why am I looking at this? Why am I living it?” And I quit within a week. And I went to Pennsylvania and I got a job and I worked with my dad’s company and worked with this and that.

I basically then proceeded to lose money for like 20 years developing technology until it started to work. But when it started to work, oh my God, we ended up the first Triple Crown winner in 37 years. We brought more world champions and the greatest stakes are the biggest races and we won more. Bought more at below auction average prices more of those than anybody in history. Not that most people either realize it or pay attention because it’s so insular and…

Meb: This is all obvious, I feel like, to a lot of people now in retrospect. You have the Moneyball for baseball, you have people talking about…

Jeff: 1970.

Meb: …the sports analytics revolution. Right. And not at the time. So, tell me about the early days. When you talk to the trainers and the buyers, what was… You mentioned pedigree.

Jeff: That was number one.

Meb: Was that kind of the number one factor in determining what…?

Jeff: And they had all kinds of experts, there were encyclopedias and the entire bazillion facts of the stud book. And yet the best, the number one, the top 1% most expensive stallions, maybe 5% or 10% of their offspring were any good. And if 1% or 2% won a championship, that was a big deal. “Oh, look, it’s because of his pedigree.” And I’m thinking, 99% weren’t that good, 99% were bad. How was that a powerful… And because you all believe it, those horses get the very best veterinary and the very best training and the very best this and that. And I got a good long look at what the difference between the average and the very best was. Your basic race track is like a hospital where all the doctors got their MD in a two-week correspondence course. High school graduates, illegal aliens being paid under the table walking the horse. I mean, I was a pointy-head. They thought I talked funny. Well, what I think was…

Meb: What was your wedge in? What was your initial insight?

Jeff: I went to one of the most famous…the guy who won the Triple Crown with Seattle Slew, Billy Turner. And he had come up to the steeplechase ranks. I met a girl named Patty Miller. I hired her to help me break a young horse I had. And she was a leading amateur steeplechase rider. And she was fascinated by what I was doing. And she was a friend of all the steeplechase people. And basically, she took me to people. And he worked with me. I worked closely with Billy Turner in the first three or four years. And I brought the Olympic stuff over.

So, anyway, I quit my job and then I did it, and then I started that thing with the Olympics thing. And then I got to work with Billy Turner. And we started having some really good horses for people. And George Strawbridge was a neighbor like a mile away. So, Patti, she knew him personally. So, he tried me out. Among the first few horses I bought him, I bought him a world champion in the first year for the average price at that auction. And then the next year I bought him another world champion, two in a row. Most people don’t even get close to in an entire lifetime.

And then one other guy who had been leading in the country, Eclipse Award-winning breeder and a racing guy named Ken Ramsey, a good old guy from Kentucky, from Lexington and a gentleman, a wonderful guy. Anyway, she got me to talk to him. Actually, that was through some veterinarian or something. He said, “Okay. Go over my horses.” He had like 200. “And then make me a recommendation. Let’s see what you got.” So, I went over all his horses and I called him back and, like, in three weeks was the Belmont Stakes. And I said, “I want you to enter Nolan’s Cat in the Belmont Stakes.” And he burst out laughing. The horse did not want to race. But it was by his new sire he was trying to promote, Nolan with his son or his nephew or somebody. It was Nolan’s Cat by Caddy Ansys, who was the sire name. I said, “I’m serious.” He said, “What are you talking about? It’s a maiden. It hasn’t won a race.” I said, “It hasn’t won a race because you haven’t sent it far enough.”

The Belmont Stakes is one of the longest races ever in the whole season, it’s a mile and a half. Most of them are half that or less. I said, “I know he’s not fast, but he never slows down. I’ve done my homework. You’ll see him by the end of the race, you’ll be picking up horses. You’re going to be in the money. You got a chance.” And not only that, but then it’s the grade one race. It’s a classic race. Then the first crop of your south stallion you’re trying to promote. In his first crop, we had a classic horse that was competitive with classic grade one championship races. So, he entered the horse. And the trainer, it was a well-known trainer, Dale Romans, was furious and pissed off. When I got there and the daily racing form review of the Belmont Stakes the day before, they said, “This horse, and this horse, and the pedigree, and the blah, blah, blah.” And then there’s the jokers and then basically the nincompoops and they’ve got to enter the horse for vanity purposes, don’t know what the hell they’re doing. That was me with Nolan’s Cat. By the way, I never got an apology from those turkeys.

Anyway, so, I got there the day of the race and went right before the race and the trainer was there and he was pissed off and he said, “They’re forcing me to do this.” He’s telling the press and this and that and the other. Then they come out of the gate and Nolan’s Cat, of course, is dead last and the trailing the field, which I knew would happen early, but I wanted to hide under the table because I knew this was going to be, like, mega humiliating. The wise-ass from Harvard flexing up. And then we get about halfway through the race and he’s starting to catch up. And then we get about two-thirds of the way and he’s starting to pick up horses. And by the end, he’s flying and he stirring and looks like he might actually catch the winner and he’s third. And in the Belmont Stakes, grade one. And to prove it wasn’t a fluke, then later on in $1 million, it was either the Louisiana Derby or the Delta something, the $1 million race, he was second or third again. And so, it was me, the point was made.

So, Ramsey hired me and I started doing work on his horses and bringing some of the technology. I also had looked into interval training. That was all the rage back then. They thought the Germans were winning, the East Germans, because of interval training, it was more because of steroids. But it doesn’t work on horses. But it was all the rage and everybody would try to move it over into horses. I could give you a half an hour speech why it’s a waste of time on a thoroughbred racehorse. In fact, it’s harmful. But I did the work to find that out, I had to fail at it trying it. I invented the first…there was no highway meter that was accurate on racehorses. They were all using human meters. And because the horse twitches off flies with a little electrical muscle in its skin, it would screw up the EKG signals and the electrodes would move around. I had to invent electrodes, and then I had to invent a heart rate meter that had a QRS interval autocorrelation function. So, there had to be a Q…it had to look like an EKG to be counted as a heartbeat. And so I invented the first successful accurate racehorse the size of a pack of cigarettes. I ended up selling it to all the research universities, but nobody in the racetrack would buy it.

When somebody at the racetrack stole one, we had a party. Anyway. So we invented that. And then we went after…we decided the interval training was a waste of time. But some people thought it was the size of the heart. There was a guy in Australia who measured hearts in autopsies and he would listen to hearts. And he took an EKG and he claimed you could correlate it to the mass of the heart and that was what was really important in race horses. And so, I looked at the whole thing, I studied it, and I said to myself, “I’m also a good mechanic.” I went through General Motors mechanic school, and I went to night school in Somerville when I was at Harvard to learn jock mechanics because I wanted to work on my own motorcycle. Anyway, a pretty good mechanic. Anyway, I looked into what this guy was doing, I said, “This little shitty machine that the EKG is being printed out on.” He’s measuring to the millimeter on the tape, right? I said, this little motor in there is going to go faster or slower depending on all the barn electricity is notoriously surging up and down and all over the place. It’s going to go faster and slower. And so these things are going to be varying depending on how clean the power is in the barn. And I know in these barns, it’s crap. So, the wiring is not the code in most places in those days.

So, I said, “This is not going to work. We have to measure the heart directly.” Anyway, we built from an Apple 2C computer and all kinds of other crap and programming in machine language and we could measure the distances of the thickness of the heart and the volume of the heart and how much it pumps. We were the first ones to do it. It got copied. Now you can buy it off the shelf. I didn’t patent anything. And it’s all been stolen and it’s…that’s where they come from now for the horse part. Anyway, so we did that. And then we were working on breakdowns, the black box stuff. And then in the end, we used A mode ultrasound, pitch and catch ultrasound to measure the bone strength, same kind of logic. We said, they were measuring bone strength by trying to do it by how much calcium there was or all kinds of ways that were not direct. I said, “Why don’t we just measure it direct?” The elastic modulus of the bone was directly related to the speed of sound through it. So, if we can get a duplicate of the path that we’re getting through the bone, we’ll be directly measuring the speed.

I went and collected the legs of every horse that broke down at one of the local racetracks, and I froze them and sent them out to MIT. We put it into an angstrom unit and we duplicated the timing and quantity of forces of a race. How did I know that? I buried force plates in a racetrack and used my high-speed camera and coordinated all the shit to get the timing above everything in the gait and how much force there was. We put transducers on horses hooves and things. And for everything that we did right, we did nine things wrong. We had disasters. We would have one, we had everything wired on the horse and the horse would be going and everything would come apart, and break, and the jockey would get hurt and everybody would be pissed off and things like that. And one time, there was a delay on the frozen legs going to MIT. And so it got held at Logan Airport and it thawed out and it was blood coming out of the…and the FBI and everybody came, they opened the box…

Meb: I was just picturing the poor receptionist at MIT or the delivery person delivering a bunch of horse legs or frozen horse legs.

Jeff: Well, the one that wasn’t frozen created a stir.

Meb: Yeah.

Jeff: Anyway, we figured out that we could in fact predict when the bone would break from the speed of sound through the bone. And we ended up…we couldn’t get anybody to use it. We were going to charge 10 bucks each time. The horses break down, there was 5,000 a year. I don’t know if you read the thing. One of the big disgraces in a horse race is how many horses are breaking down, five dying a day. If in professional baseball they were hauling five pitchers off the mound dead a day, I think maybe it would be a scandal, but it wasn’t for the horses. So we had a big meeting and there was an MD at the meeting. And he says, “If you can do that, that’ll be a great non-invasive bone scanner for osteoporosis.” So, we contacted Johnson & Johnson and they bought the whole thing. And they ended up, it’s a major thing now, they use it. It never came back to horses. And it came out of little nut kegs in a little shack in a cornfield where we did all our work.

Meb: But that’s usually where the innovation comes from. It’s often not repeating just what people have done for decades. And of course, the horse race is hundreds of years. And you mentioned so much with analytics is just proving commonly held beliefs. This happens in my world of investing all the time where people just parrot and repeat what they’ve heard without ever testing it, and often it’s, A, not only true, but in some cases 180 degrees in the wrong direction, and so…

Jeff: Yeah, that’s what I found.

Meb: And now, a quick word from our sponsor. Uranium, the fuel for nuclear power is generally considered a contrarian investment whose returns are typically not correlated to other asset classes. Low uranium prices lasted for many years after the Fukushima meltdown, leading to substantial supply destruction. And today’s prices, uranium mining is considered uneconomical even for the world’s lowest-cost producers. According to Morgan Stanley Research, uranium demand is already estimated to exceed existing supply, and future demand growth is expected. New mines aren’t economically viable at today’s prices according to some analysts who predict the price of uranium may need to double to over $60 per pound to incentivize sufficient new mined supply to meet expected demand.

The NYSC listed North Shore Global Uranium Mining ETF, ticker symbol URNM, offers investors exposures to both miners and holders of uranium. For more information, visit urnmetf.com. The foregoing information is not intended to be recommendation to invest in uranium or any uranium and related investments. Please consult an investment professional for advice specific to your situation. And now, back to the show.

And so, talk to me about some of the…you mentioned the heart. I mean, that was a big insight for you. What were some other things? You said pedigree is not as important. Anything else in particular that stood out as being big insights that either did or did not contribute to horse’s success?

Jeff: There was a team at Harvard that were doing studies on treadmills with quadrupeds, four-legged animals from turtles, to elephants, iguanas, to gazelles, cats, dogs, and horses. And they were creating equations to describe it. It was bioenergetics equations. And people latched on to that. We’ve had a lot of people who’ve tried to copy us, but they’re so half-assed because they don’t have the expert…they don’t go to major…we went to major luminaries in each of the fields of major universities. We spent enormous amounts of time and money. They try to do it all on the cheap.

But anyway, so they publish these equations. So, a lot of people said, “Oh, we’ve got biomechanics of racehorses.” And they would apply these energetic equations to tell you who’s a good racehorse. But they were developed from iguanas and turtles and elephants. They were really good for telling you whether it was an iguana or an elephant, but they weren’t good for telling you whether it was an ordinary racehorse or a great racehorse. In fact, they were totally useless. I knew because I had spent a year and a lot of money and I had computer printouts of SAS, the statistical package, on exactly that, on horses gaits and the bioenergetics, all the biomechanical literature, all the stuff coming out and veterinary literature on it, and that was supposed to be gospel. And it was just wrong. It was useless.

And the heart stuff. I went to the leading cardiologist in horses in the world and I talked to him and he showed me a big horse’s heart in a jar and said, “Well, horse’s hearts don’t go as fast because look at the size of this and that.” And at the time, they thought the horses when they were galloping, like maybe 120 beats per minute. That was a big snag in developing my heart rate meter, because they kept giving me numbers like 250. I thought there’s something wrong with this. There’s nothing wrong with it. When they were rocking and rolling down the stretch, they were up to 220, 250. And not only that, but their resting rates were as low as 25. And when you walked into the stall, that rate could go from 25 to 120, bang, like that. So, the heart was not only going faster than the human heart when they were at peak exercise, but it’s more labile, it can go up and down more rapidly. The horse doesn’t seem to have turn to hair and he’s going from 25 beats a minute to 120 beats a minute just by looking at you.

And so, we learned a lot. We were learning about the horse. And we found out there were swimming horses. And we found that when you swim the horses, a lot of them panic and their heart rates go right through the roof and into arrhythmia, and it hurts them and they end up blowing capillaries in their lungs and bleeding out their nose and it’s a health problem forever. We also found that the standard thing they were doing with the young horses when they started training them, the two-year-olds, some of them would go into arrhythmia and scare the shit out of them. And they would never run as fast as they could again. Horses are like that. They have a memory. If you walking a horse, a young horse, and you slam it, he won’t go through the gate, so you get mad and slam the gate on it, that horse will not be good around gates the rest of its life. And so if you take a young racehorse early on and scare the shit out of it, give it arrhythmias every time you make it fly, it’s never going to try to keep up with the big athletes again. That meant that we had to walk in to people who were successful and famous trainers and say stuff like that, that you’re doing stuff wrong. And I was nobody who knew nobody. And they’re thinking, “Who is this asshole from who already thinks he knows something?”

Meb: And what was the actual sort of on-ramp as far as disclosing your methods that you thought worked? As you mentioned, I’m assuming the reaction from most…

Jeff: The big on-ramp was after Ramsey… Ramsey didn’t do it, even though I was working with him. He wouldn’t tell people how good we were. Why would he want somebody else to use this? And Strawbridge, he got to two World Champions, but it didn’t seem to make any effect on anybody else. And it was the first two we’d ever had, really. He had some in Europe. But after that fairly young, successful Egyptian businessman made all his money with breweries in Egypt. And somehow the alcohol was forbidden in radical Islam or traditional Islam. But they do have breweries and somehow his family got the right to all the breweries. And he made a lot of money. He wanted to go into racehorses. And he was in like his second year in racing. And so he gave me free rein. He would buy like $20 million of horses a year. And so we took him from dead start to the top, the number one stable in the United States in two years with a budget much lower than the Arabs or some of the other traditional guys who spend, $20 million sounds like a lot, but they spend a lot more. And that got noticed. They said, “Holy shit. What’s his secret?” He was very smart. He was a good manager, and he had great trainers, and we couldn’t have done it without him and the access to great trainers. But it was also us. They couldn’t have done it without us. We were the Moneyball. That was like 20, 15 years ago or something. And it ended up like 5 or 6 years later, American Pharoah won the Triple Crown first time in 37 years.

Meb: Tell us that story, because it’s a good story. And I imagine most of the audience hasn’t heard it, but…

Jeff: American Pharoah story?

Meb: Yeah.

Jeff: Well, first of all, we bought the dam, and we were responsible for keeping the sire Pioneer of the Nile. And then the dam, little princess Emma, and she got hurt, like, in her second race, but she had talent. So, the reason we bought her was she was fit all these new criteria. Heart, the gait, the this, the that, the diameter of her spleen, all these things. She was a very rare physical wonder. And so she became the mother of American Pharoah. And then there was the Arab Spring, and the Egyptian pound went down like 50%, and the military businesses were…and the military guy was out. And the business was kind of like trouble getting money out. His business partners were military. So, he was really affected by that. And he had this yearly that was beautiful. And our job was not only to buy horses, but to tell him what to keep and what to sell. So, we go to Saratoga and we evaluate this horse. And he thought maybe he could sell it for $1 million because it’s beautiful. And we said to him, “No, don’t. I don’t know if you have a cash flow problem right now, but don’t sell this horse. This is really something.” And we got to the point we said, “Sell your house. Don’t sell this horse.” Somehow that got her. It was the quote of the day in the New York Times. Friday in June, it was June 5th, the day before the horse won the Triple Crown. They had an article front-page center about this guy. He was a passionate guy. He was a big gambler. He was in and out of financial trouble. Very smart. So, anyway, that’s that story. Sell your house, don’t sell this horse. So, he didn’t.

Meb: I mean, and the interesting part is, you guys actually had to buy it back, right? I mean, it was on auction.

Jeff: Yeah, yeah. He had to buy it back. It was in the auction at that point. But he bought it back for $300,000, so he had to pay the commission, the 5% or something.

Meb: So, the listeners who aren’t familiar with horse racing. Triple Crown, and this was the first winner in how long? It’s been years.

Jeff: Thirty-seven years.

Meb: It’s like there’s a few records in all of sports. It’s like hitting 400 in baseball. It hasn’t happened in forever, but it’s like winning the World Series Super Bowl and Stanley Cup all in one year and one horse and it’s such a rarity. And the funny thing…

Jeff: And he also went on to win a World Championship against older horses and set track records later in that year.

Meb: Yeah, yeah. And so, you mentioned the horse went for 300 grand as a rebuy, which is great. How does the pricing of horses work? Because I know I’ve heard, what’s the record? Probably in the millions for how much a horse…

Jeff: $16 million.

Meb: Okay. That’s a lot.

Jeff: That’s private in an auction, but privately, some go for a lot more than that. But for an unraced young horse, $16 million. I was there when that happened. And the day afterwards I was interviewed and I said, “Well, there’s a problem.” The gait, it looks so wonderful is because it was using, it’s called a rotary gallop. It’s what they use to come out of the starting gate. And when they’ve changed leaves, they do it once. And it’s not the normal racing gait. The footfalls come in a different pattern. And you can’t do that in a race, the whole race, because it uses too much energy and it’s too dangerous for other reasons. And I said, “So, I think it may be why the horse never won a race.” And so the day after they bought it, I had that in the thoroughbred record magazine that they interviewed me, I said, “I don’t know.” And nobody wanted to hear that shit.

Meb: Well, it’s interesting because you mentioned, I imagine in the early days the auction markets were probably a little more “inefficient,” has that changed over the years?

Jeff: No.

Meb: Oh.

Jeff: Well, actually, it is. They are more efficient, but there’s more new money. The Wall Street kind of guys are in there now. And they’ll pay anything. And the average prices have gone way up and are kind of completely out of sync with the earnings ability of their horses. But no, I’m absolutely amazed. It is still, the pedigree is the number one thing these guys are looking at. There are all these pedigree experts. The data that they base it on is missing key variables. It’s enormous amounts of money are spent at these auctions. Everybody’s an expert. And it’s just most of it is ridiculous. They watch the horse running. They don’t use what I use, a high-speed camera, so I can slow it down. And you can’t use ordinary video because if you do, when you try and stop it, all you get is fuzz because the hooves are moving too fast. And they don’t say they need it. They don’t know who does it.

And so, I see these horses, and they do things, when you look in slow motion that you know they’re going to get hurt. And they go for $400,000, $500,000. Or they have something or they have a pea heart. They have a tiny heart and their chances of winning are graded stakes are like 20% of what they would be if it was normal. And they go for, because they got a great pedigree and they look good, they go for a ton of money. Or they pay the most money for the fastest horses. Horses that go 9 and 4/5 second for an eighth of a mile. And then, oh, as the fastest breeds at the show for the auction. And 10 flattened. But in a race, they don’t go that fast. They don’t go nearly that fast. They go a second or two an eighth slower than that. So, what is the point? So, if they go nine and four then, if the horse can go nine and four, what does that prove? It may prove the opposite of what you want. Now you have a horse that can win the first half of the race and then he’s going to die, or I watch it in slow motion, they say, “Yeah, it was fast all right.” And it was ugly. You should see what was going on with its ankles were twisted, and its knee is in the wrong direction. And it’s not how fast they go, it’s how they go fast.

And then everybody seeing pretty much knows, there’s articles about it all the time, that the horses at the yearly and two-year-old auctions, the unraced young horses that go for over $1 million most of them never do squat, but they still are just…every one of those sales, there’s multimillion-dollar horses sold. We did what we did for Zayat, and our average acquisition price was $155,000. We didn’t just have unlimited budget so we could buy all the best horses. That’s what they think, “Well, I don’t get the best horses because I can’t spend the big money or either, blah, blah.” Bullshit. It’s because they don’t know what they’re doing. But you can tell that really makes friends in…

Meb: Wow. There’s so many parallels to our world in the investing space, not just on public stocks, but you see this with the private venture capitalists that will pay up in these massive rounds that you question, is it more about the investment in the business? Is it more about sort of the signaling? You see that with the tuna auctions in Japan where people pay these just insane amounts of money for a single tuna.

Jeff: Well, that still goes on. It’s still people drinking beer and being silly. But I was going to say something else about the heart and the quant thing. One of the reasons whether or not heart size was related, for a long time it was very controversial. And a lot of people have tried to do it, but they couldn’t make it work. They couldn’t make the statistics work. They didn’t understand how we did it. The way I did it was I just really studied it and I realized that I needed to only compare horses that were within, like, 30 days of the age of the horse, the same sex, the same chronological age, not just generally, but very precisely. And they were the same height and weight, because, you know, if it’s a bigger horse it’s going to have a bigger heart. And so, if a 900-pound filly that was born in May versus a 1200-pound colt that was born in March, you can’t compare them. You can’t say, “Well, this one had a big heart and that one had a small.” So, we don’t do that.

But in order to have every combination of height, weight, sex, and all, I had to have 10,000, 20,000 horses, plus all the crap that goes into it, the drugging, and the injuries, and all the noise in the data. I now have, like, more than 50,000 horses in that database where we rigorously would…and we had a technician who was…we proved we could be reproducible. The average person guy where they would read our paper and they would try out and do it, they would think they were going to get reproducible results, but you don’t train a technician for something that precise. They got to practice it. They got to do it hundreds of times and they’re not going to be reproducible. So, I tell people, “Well…” I remember some vet was telling our client, well, they could do everything, they’d read the paper. And I said, “Well, that’s like giving an instruction book and a violin to somebody and thinking they can play a symphony.” It’s not going to happen. You have to do the 10,000 horses and 50,000 and you have to have a technician that’s done a thousand. It’s got to be rigorous and it’s a lot of time and money to get it right. And there’s no shortcuts. But once we had the data, all of a sudden, what seemed to be about the heart size versus the horses would seem to be impossible to prove became clear.

Meb: So, as we look to the horizon as this industry has evolved over the past few decades, what is being embraced today and what are some predictions going forward? I mean, is genotyping a thing where the genetics come into play?

Jeff: DNA is coming in now, but a lot of that has got the same problem as all the other technology introductions. People going off half-cocked and stuff with methodologies that are pretty woeful, too few horses, not enough variables considered. But I’m sure they’ll get there with it. We’ve been working very hard at that. One of them had the speed gene, some Irish outfit. And they started out with 179 horses in the same guy’s barn. And with DNA, honest to God, a lot of it, whether the gene is there, it’s whether it’s expressed, the environmental influences. There’s so many things going on. A lot of it nobody understands. They said they found the speed gene. And I thought, “That’s like saying you found the health gene.” It’s ridiculous. There’s 4 million things that go into how fast a horse runs, whether he’s lame, whether he wants to, or whether he’s fit, whether he can, whether it hurt. There’s so many things that go into it. You can’t have one gene for speed.

There was a Myostatin inhibitor. There’s a disease where this gene can make a baby look like a weightlifter, or a little dog look like muscled up. And so the horses that had…so, they would be muscled up prematurely. And I was thinking, “You think that’s all there is to a good horse?” It’s so ridiculous. And call it the speed gene, but they got a ton of money from investors, and they’re selling all over the place. So, what we did was we went back to our databases and took DNA samples on variables we knew were precise on one attribute, for example, not like health, but like Lou Gehrig’s disease. So, we did it on the thickness of the scepter walls, the left ventricle, and we had those measurements, we knew it related to performance. Could we find markers for it? And that kind of thing. And so we’ve been developing. We actually have markers now that somehow help us identify the horses we used to have to do 22 tests on. And we got a lab in Lexington and the guy can do it overnight. And I had to search around for a guy in DNA. He’s an MD. And I needed somebody who was reasonable, rational, honest, not a promoter. So, that’s what we’re doing. And it’s coming. That’s going to be the next big thing. And then the pedigree guys will all have a heart attack.

Meb: Well, that’s because they don’t have big enough hearts or left ventricles. You got to sort the…

Jeff: There will be all these pedigreed horses are going to come back where they’re missing key markers and it’s just all that expertise they think they have will become worthless. Well, it was always worthless, but they’ll just finally realize it.

Meb: You alluded to this earlier. But if you had to break it down as to say, how much of the horses eventual success is its tools? So, it has all these 9 out of 10, 10 out of 10 on all your metrics. And how much it is the actual training jockey and doing that the right way? Because you alluded to certain things you shouldn’t be doing in the training and racing the horse as well. Is it like 90/10, 50/50?

Jeff: Well, the 90/10, 50/50, I mean, that way of thinking about it is not maybe the best.

Meb: You can say foolish.

Jeff: No, I won’t say foolish. No, it makes sense…

Meb: Misguided?

Jeff: …but it’s not… I can’t answer that question. I know that if they don’t have…it’s more like the champions are like the chain holding the Queen Mary. If one of the links is paper mache the chain breaks and the ship drifts away and you’re screwed. Horses have, it’s incredibly complex. Any one hole is a disaster. Really good horses may not be the best at everything, but they don’t have holes in them and they want to do it. I mean, second, you don’t have to make them run. I’ve ridden racehorses in practice. The good racehorses, if you go out in a group of five horses, they want to be in front. If you don’t let them be in front, they’ll fight me the whole way, they’ll kick, they’ll try to throw you off, they’ll kick other horses. And then other horses don’t give a shit. They’re happy to go on the back. I don’t know where you get that from.

When somebody figures that out, that’ll be great. Or if they could get a horse that could speak Spanish.

Meb: One of the insights I heard you mentioned before was talking about horses on the longer tracks. It’s less that they run faster at the end and more that the other horses are slowing down.

Jeff: Absolutely. But let me just say something about the 90/10 thing. Not just 90/10, but you want to think about the missing link or the weak link. But I think they have to have the stuff. I think, like, 50% is what I do. The jockeys are mainly there not to fuck it up. And there’s four main ways they can, make a horse go too fast early, they can interfere with them, they can hold them too tight, they can do this, they can do that. Some horses don’t want to run in company. Or they have such a long stride they can’t stretch out without clipping heels. So you have to keep them on the outside. There was a champion named Lookin At Lucky. Whenever he was inside among horses he lost. When he would come to the outside so he could stretch out, he had a huge long stride, he went by. So you had to know that and tell your jockey and have him do it.

But the trainer is critical. And I don’t know why. We’ve had two or three phenomenally successful runs with some people for some trainers. And then we’ve had the same groups of horses go to other trainers two or three times in big groups and they did poorly. And they were the same horses. So, some of these guys could take Secretariat and not win a big race with him. And so the trainer is critical. I mean, some of it might be what they feed. You can screw it up by feeding them too much hay the night before the race by not having good management control over your help. Or maybe there’s just drugs. I don’t know. I tell owners, I say, “If you’re going to hire me and you really expect the kind of results I’ve had with the major stables where I’ve been really successful, then the trainer you use is absolutely critical and there aren’t that many good ones, in my opinion. They’re good, but they’re not great, and you need great.”

Meb: Well, given the time of year, we can’t not ask you, and I promise I won’t hold you to it, but how’s the field for the derby look this year? Any favorites?

Jeff: I’m really good at picking the Kentucky Derby because it’s the first time they go a mile and a quarter. And what you said is right. The horses that usually win are not the ones that speed up at the end, it’s the ones that don’t slow down. And there’s another reverse of the paradigm. We handicap, not by how fast they go, but by how they slow down, and we do really well. Because almost always when you see a horse passing everybody, he’s just not slowing down as much as the others were. We all have a list for the Kentucky Derby and we’re really good at handicapping it, but I don’t have it yet. I’ll have it later in the week.

Meb: Good. Well, I’m going to hit you up for it.

Jeff: You can go to our website. Maybe I’ll put it up on our website, eqb.com.

Meb: Please do. EQB. We’ll link to it in the show notes, listeners. I’m less scientific. I’ll probably do, what is it? An exact trifecta. There’s two horses that have bourbon in their name.

Jeff: There you go.

Meb: Being in Kentucky, that makes sense.

Jeff: One of them got loose, I think it was this morning, and ran all over the place.

Meb: So good to know.

Jeff: Got away from this groom when he was taking a bath and he ran all over the place, ran through manure piles. They have a video of it somewhere on the Internet, one of the bourbon ones. The Kentucky Derby really is a proof of the paradigm. You want to know what horse isn’t slowing down, not who’s the fastest, because it’s a longer race than they’re used to.

Meb: So, if you look back on your career, has there been a most memorable horse? And if you say American Pharoah, you have to say a second one. I imagine that certainly seared into your brain.

Jeff: The most memorable horse was Pinkie Polanski. I was trying to run a charity and raise funds with this charity in Philadelphia working with inner-city teams at the time. And Pinkie Polanski was my biggest contributor. He earned like $200,000 15, 20 years ago for that charity. I named him, my father used to take funny names out of the newspaper for my sister. And I named him after that. But it turned out Pinkie Polanski was the rider for Citation. He was his exercise rider. He was the best rider for Hal Jones who was a legend in horse racing. And they had to protect him because he was gay, he was openly gay back in 1946.

Anyway. So, I named the worst Pinkie Polanski and people came…I bought it for $35,000. And one of the things was, when I went to see him before we bid on him, I kind of tried to get a sense of what he was thinking and everything. And somebody said to me, “Well, what’s he thinking?” I said, “He’s thinking, ‘What are you looking at?'” He had the greatest attitude. He had a crummy pedigree or no pedigree at all. He was not intimidated by anything or anybody. Billy Turner trained him for me, the guy who trained Seattle Slew. And we had a good run and a lot of fun. I managed him very poorly then. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. I had a mile and I tried to run him further. He was very fast. That was like a 21-year-old record at Laurel Kelso who was like a horse of the year seven times had set, 21 years that it set, he was equal that track record. And he still lost to some horse that day. But anyway, I just loved that horse. And he was funny. Pinkie Polanski, we had a lot of fun. And somebody said, “Well, it’s about time somebody named the horse after Pinkie Polanski.” And I said, “Why?” And they told me the whole story. And I didn’t believe it. So I was at a dinner table with somebody, the guy who was down at the sale one time and there was a trainer there who had been a groom for Hal Jones. And I asked him, “Was there a special rider?” He said, “Oh, yeah, Pinkie. When he died, they found $20,000 in his mattress at the racetrack.”

Meb: How much of a role and influence does the gambling world play? There’s been some analytics on that side with the Alan Woods and Bill Benter’s of the world. Does that have a pretty big influence? I actually saw yesterday that, this is new to me, but there is now an online, I don’t know if you call it a video game, but a website called ZED RUN that lets you buy and invest and breed in digital crypto horses. And there are people that have paid $10,000 to $100,000 to own some digital horses, which is a sort of crazy idea.

Jeff: That’s wild.

Meb: Yeah. It’s called ZED RUN.

Jeff: Well, in my experience. I work for some of those whales, the big betters. And I’ve developed stuff along the lines what Alan Wood did, algorithms. And you have to be able to do like 50 bets right before the gate opens, bang. If it’s a rank link, not just to the racetrack, but to the tote, which is the racetrack is sending. I’ve done all that, I know something about it. And it’s interesting. The whole sport, basically, is supported by gambling and betters. And most of the betting is done by a relatively small number of people. But there’s no crossover between the horsemen and most of the racing owners and fans. And the big betting stuff that’s driving the economics. It’s just really very separate. And the Alan Wood kind of stuff really doesn’t care who wins the race. They are arbitraging the difference between all the cracks in the system, basically, and they don’t care. They can make 1% or 2% a day, which is 60% a month. So, what do they care? And they’ll bet six horses in a race with eight horses in it. How much you bet on each horse is all quant stuff. But I’ve moved in that world, I’ve worked in that world. It just seems to be totally unconnected, except that the racetracks have figured out who these guys are and they create offshore places where they can bet on the, they try to find all ways to separate out that income and keep more of it for themselves and they have to share other kinds of bets with the horsemen and the state. But it’s just another strange thing about horse racing, that there’s such a disconnect.

Meb: Well, Jeff, this has been a lot of fun. You mentioned it, but where do people go? They want to find out more about you and find your Derby picks, what’s the best place?

Jeff: My website. I’ll put something up later in the week. EQB like equine biometrics, eqb.com. That’s us.

Meb: I love it.

Jeff: But I never did it for the money. I love horses and I wanted to work with them. It’s a Damon Runyon story every day at the racetrack. It’s fun, guys and gals.

Meb: Good. Maybe we’ll Jenny up a syndicate of podcast listeners and all buy fractional shares and a horse next year. But I got to warn you, all my followers like me are cheap bastards. So we’re going for the undervalued horse.

Jeff: Well, that’s fine. It doesn’t bother me. That’s actually good because then you’ll buy the scratch and dent with something wrong and it doesn’t make any difference. Or you’ll buy the one with supposedly a Pinkie Polanski with no pedigree

Meb: I love it. Jeff…

Jeff: And be the giant killer.

Meb: Thanks so much for joining us today.

Jeff: Thank you for having me.

Meb: Podcast listeners, we’ll post show notes to today’s conversation at mebfaber.com/podcast. If you love the show, if you hate it, shoot us feedback at feedback@themebfabershow.com. We love to read the reviews. Please review us on iTunes and subscribe to the show anywhere good podcasts are found. Thanks for listening, friends, and good investing.