Episode #437: Edward Chancellor – Interest, Capitalism, & The Curse of Easy Money

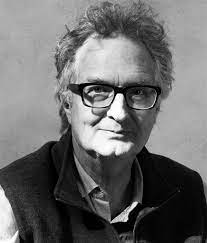

Guest: Edward Chancellor is a financial historian, journalist, and investment strategist. His newest book is titled The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest.

Date Recorded: 8/3/2022 | Run-Time: 1:03:11

Summary: In today’s episode, Edward walks through how interest, debt and money printing are related to things we’ve seen in society today and the past few years: zombie companies, bubbles, and massive amounts of paper wealth. Then he narrows in on current day and shares why he believes low interest rates are causing the slow growth environment the world’s been stuck in over recent times, along with the bad kind of wealth inequality.

Sponsor: Masterworks is the first platform for buying and selling shares representing an investment in iconic artworks. Build a diversified portfolio of iconic works of art curated by our industry-leading research team. Visit masterworks.com/meb to skip their wait list.

Comments or suggestions? Interested in sponsoring an episode? Email us Feedback@TheMebFaberShow.com

Links from the Episode:

- 0:39 – Sponsor: Masterworks

- 2:14 – Welcome to our guest, Edward Chancellor; The Price of Time; Devil Take the Hindmost

- 5:38 – The relationship between technology and democratization with bubbles

- 12:37 – The origin story and motivation for his new book

- 16:30 – The history of interest rates

- 29:03 – How quantitate easing has been around for centuries

- 33:48 – Stocks Are Allowed To Be Expensive Since Bonds Yields Are Low…Right?

- 38:04 – What low rates have contributed to

- 41:08 – The End of the Everything Bubble, Alasdair Nairn

- 43:10 – Ed’s thoughts about living in a time of higher inflation and financial repression

- 54:17 – Ed’s most memorable investment and lesson learned from writing his book

- 59:36 – Learn more about Edward; Reuters

Transcript:

Welcome Message: Welcome to “The Meb Faber Show,” where the focus is on helping you grow and preserve your wealth. Join us as we discuss the craft of investing and uncover new and profitable ideas, all to help you grow wealthier and wiser. Better investing starts here.

Disclaimer: Meb Faber is the cofounder and chief investment officer at Cambria Investment Management. Due to industry regulations, he will not discuss any of Cambria’s funds on this podcast. All opinions expressed by podcast participants are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of Cambria Investment Management or its affiliates. For more information, visit cambriainvestments.com.

Sponsor Message: Are you okay with zero returns? I’m talking about a flat lining portfolio, because that could be the best case scenario for stocks according to Goldman Sachs, and they’re not alone. J. P. Morgan’s Jamie Dimon said investors should brace for an economic hurricane. I don’t know about you but I don’t want the roof ripped off my house. So what’s the key to financial survival? How about diversification? Perhaps diversifying beyond just stocks and bonds that could be real assets, like art. That’s why I’ve been investing with my friends at Masterworks since 2020, before inflation it was even in the headlines.

I did an interview with their CEO in episode 388, and he highlighted to me arts’ low correlation to equities. We can see this in action. Even as the S&P 500 had its worst first half in 50 years, art sales hit their highest ever first-half total, an unbelievable $7.4 billion. Of course, who wouldn’t want to capitalize on this momentum? Right now demand is through the roof, and Masterworks actually has a wait list. But my listeners can skip it by going to masterworks.com/meb. That’s masterworks.com/meb. See important Reg A disclosures at masterworks.com/cd. And now, back to the show.

Meb: What is up my friends? We got a really fun show today. Our guest is Edward Chancellor, financial historian, author of one of my favorite books, “Devil Take the Hindmost,” and previously part of GMO’s Asset Allocation team. He’s out with a new book yesterday called “The Price of Time, the Real Story of Interest,” which is equal parts history, financial education, and philosophy. Today’s show, Edward walks through how interest, debt, and money printing are related to things we see in society today and in the past few years, like zombie companies, bubbles, and massive amounts of paper wealth.

We even talk about who was doing QE thousands of years ago, then he narrows in on the current day and shares why he believes low interest rates are causing the slow growth environment the world’s been stuck in recent times, along with the bad kind of wealth inequality. And also, how many podcast episodes do you get to listen to when the guest describes someone as “half-Elon Musk, half-Ben Bernanke?” One thing before we get to today’s episode, on August 18th at 1 p.m. Eastern, 10 a.m. Pacific, we’re hosting a free webinar on the topic of “A Framework for Tail Hedging.” Check out the link in the show notes to sign up. Please enjoy this episode with Edward Chancellor.

Meb: Edward, welcome to the show.

Edward: Pleased to be with you.

Meb: Where do we find you today?

Edward: I’m in the West Country of England on a sunny afternoon.

Meb: It’s time to head to the pub for a pint for you and for me to still have some coffee. You got a new book coming out. I’m super excited, I’ve read it, listeners. It’s called “The Price of Time, the Real Story of Interest.” It’s either going to be out this week when this drops, or if it’s not, preorder it because it’s great. Those students of history out there may know Edward from “Devil Take the Hindmost,” one of my favorite books, “A History of Financial Speculation.” Before we get to the new book I have to ask you a question about the old book. What was your favorite bubble? Because I have one, and as you look back in history, or mania, is there anyone that speaks to your heart that you just said, “You know what? This one, this was really it for me. I love this one.” And then I’ll go after you do.

Edward: Sure. In “Devil Take the Hindmost,” I suppose the one that I liked most was the one that had perhaps been least covered in other accounts of manias, and that was the, if you remember, the diving engine mania of the 1690s, when there was treasure ships were going out with rather primitive diving gear. And one of them struck gold off the coast of Massachusetts with a huge return for investors. I can’t remember, sort of, 10,000% return on investment, so you can guess what happened next. Every Tom, Dick, and Harry was making a diving engine promising to salvage Spanish treasure ships, and this was just at the time when the stock exchange was getting going in London in Exchange Alley.

And these new companies were floated there, and some quite respectable characters were involved. Sir Edmund Halley was the astronomer royal, a great scientist, was behind one of them. You get the picture. And then a lot of them were completely dodgy, and needless to say, there were a lot of stockbrokers, or what were then called stockjobbers, who were selling the shares. And that, to me, is the first technology mania and it didn’t last very long, and all the diving engine companies collapsed as far as I know.

Meb: You know what’s funny? As you walk forward, what is that, 300 years, you have the modern technology finally catching up, where a lot of the marine exploration has gotten to be pretty sophisticated. And all of a sudden, you’ve seen some of these wrecks get found, and then governments and all the intrigue on who’s claiming what in the Caribbean, whether it’s a Spanish vessel but it’s in Colombian water. There’s even, for listeners, you’re going to have to go do a little due diligence. There was a publicly traded Odyssey Marine Exploration company, it’s probably out of business. Let me check real quick. That was their entire business model, OMEX, that was the whole business model was to go and find…oh, no, still traded. Just kidding. Let’s see what the market cap is, 63 million bucks. Okay, just kidding.

Edward: Yeah, you make an interesting point. It’s that you have speculative bubbles, and the technology often does eventually catch up with the object of speculation. But the trouble is that a huge period of time tends to elapse, and the early technology speculative ventures often collapse in the intervening period. So one way of seeing a speculative bubble is a misconception of that time period. People think that the distant future is actually just around the corner, when in fact, it is in the distant future. And that’s particularly so, as you’re probably aware, when you get a rush of, sort of, new technology flotations come in at the same time. That’s always, from an investment perspective, a red flag.

Meb: Yeah, I mean, I think a classic example right now, too, would’ve been electric vehicle mania. You go back 100 years and there was a lot of electric vehicle start-ups. Now they seem to be actually hitting primetime.

Edward: Yes, and that’s quite interesting that the first and most successful listed vehicle company in America was an electric vehicle and that came to nothing. And then, in the early days of…in England in the 1890s was a big bubble in automobile stocks. In fact, my grandmother’s grandfather was the chairman of something called The Great Horseless Carriage Company that was listed by a fraudulent promoter called Lawson. My grandmother always claimed that her grandfather died of a broken heart when that company went bust, but you know, these things go round and round.

Meb: Yeah. Well, we could spend the whole time on this. Well, my favorite, of course, and this is just because personal experience, not historical, was I was fully coming of age during the internet bubble so I got to experience it from introduction to trading side. And so I look fondly and try not to be too judgmental of the Robinhood crowd the last couple years, and try not to be too preachy about, “Hey, you’re going to lose all your money but you’ll learn a lot so it’s a good thing,” and try not to be a “OK Boomer.”

Edward: I write a column for the “Reuters” commentary service called “Breakingviews,” and I wasn’t quite so charitable with Robinhood when it was coming into its IPO. I said that, you know, it was more like the Sheriff of Nottingham stealing from the poor to give to the rich than perhaps Robin Hood. And I pointed out, this is to what you’re talking about, is that E-Trade, which was both the newly listed online broker in the late ’90s, but also the object of speculation. And then, when that dot-com bubble burst, E-Trade lost 95% of its value, and I think it was later taken over by Morgan Stanley. And I have to say, I had to deal with some extremely aggressive response from Robinhood which subsequently died down because they couldn’t actually find that I’d said anything inaccurate.

Meb: Well, Robinhood, you and I can agree on that…let me make the distinction between investors learning to invest and figuring it out, and then the actual company. The actual company, I think, history will not judge kindly whatsoever. I got into it with the founder once on Twitter because they claim many times in public, in audio and in writing, that most of their investors are buy-and-hold investors. And I said, “I’m sorry, but there is no way that that statement is true. Either, A, you don’t know what buy and hold means, which I think is probably the case, or B, it’s just…”

Edward: Buy in the morning, hold, and then sell in the afternoon.

Meb: B, it’s an outright lie. And then he actually came back to me on Twitter and I said, “This is crazy but there’s no way this is true. But you know what? I’m a quant, so if there’s a 0.1% chance this is true I can’t say with 100% certainty this is a lie.”

Edward: Did you read the attorney general of Massachusetts launched case against Robinhood for what it called gamification? Gamification is really, and this is what I think Robinhood did, is it brought addictive techniques that had been refined on the electronic games in Las Vegas into the stockbroking world under the rubric of ddemocratizationof investment. And what you find is that in all eras where they claim a democratization of investment, those tend to coincide with bubble periods, and the brokers, such as E-Trade and Robinhood, that propel it tend to get pretty heavily hit in the downdraft.

Meb: Yeah. Well, the eventual response from Robinhood to me, Vlad came on and he said, “Actually, 98% of our investors are not patterned day traders.” I said, “What does that have to do with anything?” He’s like, “Only 2% of our traders are pattern day traders.” I said, “What does that have to do with buy and hold? What a ridiculous statement.” Anyway, we could spend the entire time on Robinhood. Listeners, I have an old video that was called, like, “Five Things Robinhood Could Do to Do Right By Their Customers,” and I think they’ve done none of them, so we’ll check on the tombstone later.

Edward, but it’s funny you mentioned E-Trade because this is very meta. My first online investment was an account at E-Trade, and also I bought E-Trade stock, so I was deep in it in the 1990s. I learned all my lessons the hard way, which is, in hindsight, probably the most effective way because it’s seared into your brain. But all right, let’s talk about your book because you wrote an awesome book, it’s out. What was the origin story, motivation for this book? What caused you to put pen to paper? Was it just a big, fat pandemic and you said, “You know what, I got nothing else to do?” Or you said, “You know what? This is a topic that’s been burning and itching. I can’t let it go. I want to talk about it.” What was the inspiration?

Edward: Well, this book wasn’t written … It took a lot longer than that, I’m afraid. I’d say that the last 25 years of my time has been spent largely looking at what’s going on in the financial markets at that current day, and then trying to see whether people understand it well enough, and what’s not well understood. So back in the 1990s, go back to the dot-com bubble, you’re probably aware that at the time the view in academic finance was this efficient market hypothesis, markets. There were no such things as speculative bubbles, and that the market prices, stock prices, reflected rationally all available information, risks, so on, so forth. Now that was blatantly untrue and quite evident if one read the history. So that, sort of, got me going on the dot-com bubble and I wrote “Devil Take the Hindmost,” came out in ’99 just before the dot-com bust.

I was expecting a hard landing after the dot-com bust, but no. We got this great credit group, global credit boom, and a real estate bubble in U.S. real estate. So I then spent a few years working on a…we didn’t publish it as a book to go out to retail investors but more as a report for the investment community. That was a book called “Crunch Time For Credit?” And that was trying to analyze credit, because I thought credit was misunderstood, which it obviously was going into a bit of a financial crisis when very few people seemed to understand that we were right on the edge of a precipice.

So after the financial crisis, interest rates were taken down to zero in the U.S., and to less than zero in Europe and Japan. I was, at the time, working for the investment firm GMO in Boston, and we were thinking about the mean reversion of valuations. We were worrying about why the U.S. stock market seemed to inflated. We were worrying about commodity bubbles. We were worrying about international carry trades of capital flows into emerging markets and the instability that was provoking. We were worrying about what appeared to be epic real estate and investment bubble in China, and we were also worrying about bond yields, and why were bond yields so low? And why were they not mean reverting as our models were telling us we would believe they were.

So I thought, “Well, hang on a second, we just don’t understand interest as investors very much.” And suddenly, the world, the economists, and the policymakers don’t really understand the ramifications of their ultra-low interest rates, both on the financial sectors, on the real economy, and, if you will, on society at large. So I thought, “This is a complicated subject, the story of interest, but it’s, in a way, everything…” I’m thinking the middle of the last decade when I was starting to make this a project, that everything really hinges on what interest does. And this book is an attempt to show the extraordinary richness and multiple functions that interest performs.

Meb: So the great thing about this book, it’s part history, part financial education, part philosophy. Maybe in this brief podcast, give us a history of interest rates. Listeners, you can go read the book for the full dive but we’ll talk about a few things that are interesting, because I feel like for the last few years, interest rates at zero, negative, was something that was certainly unfamiliar surprise to a lot of people. I think I don’t remember reading about it in textbooks in college certainly, but maybe talk to us a little bit about…we have a long history of interest rates in the world. Most people, I assume, think it goes back 100 years, couple hundred years, maybe to Amsterdam, or Denmark, or the … or something. But really, it goes back further than that. Give us a little rewind.

Edward: Yeah. So I open the chapter with the origins of interest in the third millennia BC in the ancient Near East, Mesopotamia. And we have evidence there in the first recorded civilization that we have documentary evidence that we can decipher and learn about. That interest was there right at the beginning of recorded civilization. And what you find in the origins of the terms for interests, in Assyrian, for instance, it’s … which means a goat, or a lamb, or in Greek it’s … which means a car. And there’s all this…the origins of interests appears to be in the reproduction of livestock, and we can guess that in prehistoric times people were lending livestock and taking back as interest some of the product of the animal.

So what we see there is that interest is linked to the reproduction to the return on capital. The word capital in Latin comes from head of cattle, so it’s all there right at the beginning. In fact, as I mentioned, Americans in the 19th century in the far West were lending out cattle and expecting interest to be paid in calves in a year’s time. But the other thing that’s interesting, go back to the ancient Near East and you find other aspects of interest. You find a real estate market, and you can’t have real estate markets, because buildings have long dated assets that have a stream of income over a long period of time. You need some interest to discount that future cash flow back to the present, and it would seem that the Mesopotamians had that.

We find that this was a commercial trading civilization, and that merchants who went on seafaring voyages raising money with loads were paying higher interest because of the risk involved in their project. So you have that element of a risk and of interest reflecting risks, as it does in junk bonds, and so forth. And then, another interesting, as I pointed out, is the world’s first laws, the Code of Hammurabi, if you look at it actually a lot of it is to do with interest rate regulations stipulating what the maximum rates of interests were on barley loans and on silver loans, when interest should be forgiven, for instance, after a flood. And what we can surmise is that even back at that time, despite this regulation, the people lending and borrowing with interest were skirting around the regulations, so what we call regulatory arbitrage.

So you see many of the aspects that one associates with interest today, the return on capital, the valuation of risk, the discounting of future cash flows to arrive at a capital value were there five millennia ago. I think it’s an interesting story but I also go through the details because I’m trying to show to the reader right at the beginning, this interest may be complicated, a bit difficult to pin down. But it seems to be absolutely essential in human affairs.

Meb: What has been the mental mindset? There’s no word that’s harder for me to pronounce than “usury,” if I even got it right this time. I always mispronounce it for some unknown reason. I don’t know why. But has there been a cultural view of interest rates and debt? Some cultures still have very specific views and social constructs around it. How has that changed over the ages? Debtor prisons, all these sort of thoughts around, who was it, Aristotle hated the idea? I can’t remember back from the book but there was one of the philosophers that wasn’t a big fan.

Edward: No, you’re right, it’s Aristotle. The third point that I think one should make is that in the great literature over the centuries of writing about interest or usury, which is really a term for an unfair rate of interest, the view has been that interest or usury was unfair and extortionate. Now this view is not wholly incorrect. If you are a peasant farmer and you are desperate for some grain or some money to buy some grain, or buy some livestock, and I am the landowner or lender and you come to me and I just press you for as much as I can get out of you. And we find, as I mentioned, in Mesopotamia, we find people taking slaves, in effect, as interest payments, and we find in Mesopotamia, in Greece, and in Rome, people falling into a debt bondage and slavery due to extortionate interest. So that’s, sort of, in a way, the well-known story of interest.

But Aristotle tried to put a philosophical gloss on why usury was bad, and he said, “The lender is asking back more than he has given.” So I gave you $1,000 and in a year’s time I want $1,100 back. So that’s unfair, I’m asking for more. And what I say is, this is, sort of, wrong, because even in the term “usury” is use, is the word “use.” And the use is that you have the use of my capital for the course of a year, and use has value because time has value, and this was actually noted. And the writings of the Greek philosopher Aristotle were, sort of, repeated by the Catholic theologians in the Middle Ages. And they said they took Aristotle, they really took on his denunciations of interest to heart.

But one of them, an English cleric called Thomas … made this, sort of, a side comment about usury. He said that, “The lender is charging for time, and he has no right to charge for time because time belongs to God.” And as you enter into the modern age, or the age, whether it’s the Renaissance, or the birth of capitalism, well, obviously people are going to drop the idea that time belongs to God and they’ll say that time belongs to man. And once time belongs to man, and once time, as Ben Franklin says, is money, is valuable, then it seems quite reasonable that a buyer and a seller should meet together, a buyer and seller of money, or lender and borrower, should meet together and negotiate a fair price for the loan of money for a period of time, particularly when that money is going to be used for a profitable endeavor.

Meb: Yeah, I’m always confused when people are, like, the argument with Aristotle will be like, “Okay, well, just give me all your money then and I’ll give it back to you in 20 years and no interest,” and that seems to be a pretty quick check against that argument. But interest rates, and historically you can correct me on this, have historically bounced around in a range that’s certainly higher than today. I don’t know what the correct range is, you can correct me. Maybe it’s 4% to 8% with the upper bound of some of the almost payday loans of today of the silver and barley. I’m trying to remember if it was 25%, 33%, or 40%, or somewhere, but it’s not 0%. And so there’s some relationship already between culture and trust, but also clearly economic development. And so are there any strings we can kind of pull, or generalizations about interest rates and economics with this not just multi century, but multi millennia history?

Edward: Yeah, I mean, there is a bit of debate about the long-term trends in interest rates, whether they’re downwards. It does seem, if you go back to our Mesopotamian loans, which I think were…I think it’s 20% for silver loans and 33% for barley loans, higher, those are pretty high rates of interest. My book is really an account of interest rather than interest rates, but the great history of interest rates is by Sidney Homer, updated by Rich Sylla called “A History of Interest Rates,” and they make a very interesting observation. It’s actually quite worrying for us today.

It’s that they say the course of civilizations are marked by U shapes of interests, so interest starting high, coming down as a civilization, progresses, and then just as civilization collapses, the interest rate taking off. And you see that in Babylon, you see it in Ancient Greece, you see it in Rome, you see it in Holland in the modern period, and you think, “Hey,” I got to say, “We’ve just had this. We’ve had this L shape with the U, and who knows what goes next?”

There’s another point made by an Austrian economist who wrote a three-volume work on capital and interest called… He makes this point that…I don’t know if it’s quite true but he says that the interest rate reflects the civilization attainments of the people. And he’s really arguing that countries, and thinking, sort of, 18th, 19th century, that countries with very high savings like Holland in the 18th century, tended to have the lowest rates of interest. And the ones with the most developed financial systems were the ones where capital was best protected by the law. So there may be something in it, but then if you thought about that comment you say, “Hey, we must be living in the most civilized period in all of history.” And you look around yourself and say, “That doesn’t quite figure.”

Meb: And so one of the cool parts about the book, you also mention things like quantitative easing. And you were like, “Yo, quantitative easing isn’t a modern phenomenon.” Tiberius was doing it…was it Tiberius? Someone was doing this 2,000 years ago. Can you tell us what was going on? And for those commentators on Twitter that are railing about, you say, “This has actually been around for a little bit.”

Edward: So Tiberius was said to sort of raise taxes and locked up a lot of cash in his royal treasury, inducing a depression and widespread bankruptcies. And then interestingly, he sort of realized he had to let the money out of his treasury, but needless to say, he gave it to the rich patricians who benefitted from the relaxing of what I call the world’s first QE experiment. But actually, we go on a much better analogue of what we’re thinking about today is what happened in the early 18th century in France, when John Law, the Scottish adventurer, arrives in France and he sees the country as, sort of, the death of the king, Louis Catorce, 1750, the monarchy is bankrupt, the nation is depressed, prices are falling. And Law says to the regent, “Let me found a bank, and I will establish a company and I will print money and bring down interest rates.” And that’s what Law did, really, in 1719 and 1720.

And the result was initially a period of prosperity, and the decline in the level of interest and this printing of money led to the great Mississippi Bubble, which was concentrated around the share price of the Mississippi Company that John Law also ran. So he was, if you will, sort of, half-Elon Musk, half-Ben Bernanke. He was a half central banker, half speculative entrepreneur. And the prices of the Mississippi Company was an enormous conglomeration of different businesses probably worth something like two times French GDP. The stock price rose, I think, 20 fold in the course of the year, and this is interesting is that Law brought interest rates down from around 6% to 8%, brought them down to 2%. And the Mississippi Company was trading on a PE of 50 times, which as you know is an earnings yield of 2%.

So the share price, as Law himself realized that, “Hey, you say this stock is expensive but it’s cheap relative to the interest rate.” Well, we heard a lot of that in the last few years. And then the other thing which is so interesting about this period is that it, as I said, initially there was a great burst of prosperity. But a contemporary banker who knew Law called Rich Cantillon, he wrote about this and analyzed the Mississippi Bubble. And he said, “Well, you can print all this money and initially it’s trapped in the financial system, but eventually there are two problems. First of all, there is no way of removing it, and second, they eventually will spill out into what he called the wider circulation, what we call the broader economy, and feed through into an inflation.

And then, the most extraordinary thing, if you read accounts of Law’s system, his QE experiment, you find that the academic economists are saying, “Hmm, yeah, this is great. Law is wonderful. He is the model upon which we base modern central banking.” And you think, “They base as their model as a guy, who admittedly very brilliant, who at one stage was like Elon Musk, the richest man in the world, but whose brief period of pre-eminence lasted 18 months and then he had a tremendous collapse.” And Law had to flee the country, lived in exile near penny less the rest of his life. To my mind, it tells you that modern central banking has built itself on very soft foundations, if you will.

Meb: It’s a great story. The analogy you made, I actually wrote an article about a year ago because I was growing weary of hearing this, but people were justifying, particularly in the U.S., high stock valuations because interest rates were low. And I think the name of the piece, we’ll link to it in the show notes, listeners, was, “Stocks Are Allowed to Be Expensive Because Bond Yields Are Low…” Right? And we basically went through at least for the last 120-plus years, that wasn’t the case. Well, excuse me. It was the case that, yes, stocks did well when interest rates were low. But it was entirely due to the fact that stock valuations were exceptionally low when interest rates were low, usually because the economy was in the tank, interest rates were lowered because everything over the past decade or 20 years had been terrible. And stocks had gotten crushed, and inflation was high, and valuations were low, all these things.

And then you had this recent period where everything was like the land of milk and honey in the U.S. for the past decade, but interest rates were also low, which was the big outlier. Anyway, it’s a fun piece. Listeners, I don’t think anyone read it. Certainly no one liked it but it’s fun to dive into.

Edward: I’ve been writing that same piece for, you know, on and off, for 20 years.

Meb: And you’ve gotten equal amount of either non-interest or disdain. Which is the more likely emotion?

Edward: I don’t know. Look, the thing is that you’re aware of this thing called the Fed model for evaluating the stock market? The Fed model is basically taking the 10-year Treasury yield, throwing an equity risk premium, a little premium for owning volatile equities, and saying that should be the fair value of the stock market. Now, it’s some level for, sort of, in short term it makes sense if you’re choosing between, particularly when, if bond yields are very low and … yields are quite high, you can see that people will, sort of, chase the higher yield. But the trouble is that over the long run we don’t find stable relationship between bond yields and earnings yields. So sometimes that’s, sort of, stable, sometimes bond markets and equity markets are moved in the opposite direction. Other times they move together.

I think in the 1970s, earnings yield on the stock market, going into the 1970s, earnings yield on the U.S. stock market was much higher than it is today. I’m talking about a cyclically adjusted earning, so not just one year, and bond yields were higher, too. If you bought the U.S. stock market on what seemed like the fair premium to the bond yield, you still actually lost money over the next 12 years. So GMO, where I used to work, we tended to value equity markets based on mean reversion of profitability and mean reversion of valuation, so we didn’t formerly pay any attention to the bond yields.

Having said that, over the last decade, and again, this is one of the reasons I got into writing this book. Over the last decade, the U.S. stock market until this year was compounding at more than 10% a year, despite the fact it was starting off at what was historically high valuation. Well, it has to be quite adaptive when one’s actually looking at markets in the environment one is in.

Meb: Yeah. Jeremy had a good quote. We cue up some of these Quotes of the Day, and he goes…this is on my Twitter from a month ago. He goes, “You don’t get rewarded for taking risks. You get rewarded for buying cheap assets, and if the assets you bought get pushed up in price simply because you were risky then you’re not going to be rewarded for taking a risk. You’re going to be punished for it.” And we got some opinionated responses to that.

So low rates, this environment we’ve been in, you spend part of the time in the book. There’s some effects/things that coincide with whether it’s a philosophical mindset on how people behave with low rates, whether it’s actual economic impact on what low rates contribute to. I live in Los Angeles, my goodness, you can go find a $40 hamburger here and you can also not find a place to live because prices are so expensive on housing. But talk to us just a little about, what are low rates contributed to, and is that all good? Is it all bad? Any lessons from history we can draw out from this current environment we’re in?

Edward: Yeah. So what I tried to do in the second half of the book is to examine the consequences of the very low interest rates, the unprecedented low interest rates that we saw in the last decade after the global financial crisis, and I look at it in different ways. I start by looking at capital allocation.

So interest is also the hurdle rate of which you lend money, which you make an investment. How soon am I going to get? What’s the payback time or period? Payback period is your embedded interest or return on capital, and I argue that the zombie phenomenon that we’ve seen really across the world, in China, in Europe, and in the U.S., where companies earning are not even earning enough profit to pay their … low interest charges that capital has been trapped in zombie companies. And that the very low interest rates have delayed and suspended the process of creative destruction, which the Austrian economist, Joseph Schumpeter, said was the essence of the capitalist process.

But closer to home, to your home, I also argue that interest is, the very low interest rates, and if you will, a desperate search for high returns in a low-interest rate world is what fuelled this great flow of what you might call blind capital into Silicon Valley. As Jim Grant writes somewhere, “Unicorns like to graze on low interest rates, the lower, the better.” So if you will, you’ve got this misallocation of capital, both into your zombies, but also into your unicorns, your electric vehicle stocks, or whatever, so that’s one aspect.

The other we’ve just been talking about is the valuation, just that the very low interest rates, the very low discount rates seems to be behind what’s called “the everything bubble,” which I haven’t read it but someone called Alasdair Nairn has written this book called “The End of the Everything Bubble.” Now, the everything bubble, as you know, sort of, particularly during the Covid market mania, incorporated everything from SPACs, to vintage cars, and so forth. And you see it, sort of, around the world, and I say go back to the bubble in Chinese real estate, which is probably the biggest real estate bubble in the history of man. And I’m saying that the rise in wealth, in reported wealth, which seems to be almost independent of actually the wealth creating activities of individuals, that there’s what you could call, sort of, virtual wealth, was a function of these very low interest rates.

And then I also talk about interest as the…what I was mentioning in ancient Babylon, as how interest rates reflect risk. And in this low interest rate period, you find as interest rates fall, people take on more risk. I think as Jeremy was alluding to in that piece you just read out, that people take on more risk in order to compensate for the loss of income. So you get masses of yield chasing both in domestic markets, high-yield, leverage loans, so forth, but also international carry trades, so it’s, sort of, financially destabilizing.

Meb: There’s a lot of weird parts to it but the negative rates was certainly a weird period. But we’ve always had this Japan outlier situation for a long time where they’ve been a low-rate environment for, I mean, my lifetime, I think, would probably be the right time horizon almost, but for a long time at least.

How should we think about living in this time? A lot of investors, particularly the younger cohort, haven’t lived in a time of, A, higher inflation, but B, what we would call “financial repression,” which, listeners, is a period where interest rates are lower than the rate of inflation. And not just by a little bit right now, and who knows how long this inflation will stick around, but by a lot bit currently. Are there some other examples in history? I know we’ve had a few, certainly in the U.S. in the past century, but as far as…is that totally a outlier over the centuries, or what?

Edward: Well, financial repression, or the policy of keeping interest rates below the rate of inflation is a tool for paying off excessive debt. And we saw that in Europe and in the United States after the Second World War, when interest rate…Britain and the U.S. had high levels of debt, relatively high levels of debt after the Second World War. Over the following 30-year period, the interest rates kept low, inflation got into the system, and really, most of the debt got paid off in the post-war period. I think in the U.S., sort of, the equivalent of 3.5% points of GDP per annum was paid off through this financial repression.

Now I think that after the global financial crisis with these zero interest rates, the central banks really started financial repression after 2008. The interest rates have been consistently below the level of inflation since 2008. The difference is that for the first 12 years, or 13 years of this period, inflation remained relatively under control within the target range of the central banks. So if you actually held cash over that period you tended to lose money. However, the other difference of this financial depression, the post-GFC financial depression, is that the system carried on taking more and more debt. And that was mainly, households were de-leveraging, fair enough, but actually U.S. corporations, as you know, were taking on debt to buy back their shares. It was a massive buyback splurge, and the U.S. government, particularly in the late stages of the Trump administration, were running enormously high deficits, which ballooned during the Covid era.

And it’s quite clear that the corporations wouldn’t have been leveraging themselves and the government wouldn’t have been borrowing so much had interest rates been at a higher level. It’s difficult to say what’s coming next. My feeling now is that we are in financial repression phase two, in which interest rates rise on the back of inflation but they still remain below inflation. But nevertheless, the gap between the interest rate and inflation allows this debt mountain to be reduced somewhat over the coming days. As I said, we don’t know the future, but I think the era of leveraged financial return, sort of what we call “financial engineering,” the era which has been so easy for private equity, and for your activist investors taking a large stake in a company and just saying, “Hey, you’ve got to buy back your shares, and borrow, and stuff,” I think that era has come to an end.

Meb: Who knows? We’ll see. I’m bullish on politicians but also governments to surprise us with all sorts of new innovations, new ideas on…and if you believe Cathie Wood, we’ve going to have 50% GDP growth anyway here for the next…some time in the next five years. So that may save us all, AI. Give us a little boots-on-the-ground overview of what’s going on your side of the pond. UK stock market stomped the U.S. from 2000 to 2007-ish, or whatever that decade might’ve been. It’s been, kind of, in a sideways malaise for a while here, man. What’s the vibe over there? Are people just disinterested? Brexit was the topic du jour for a while, and then all the Boris stuff going on. Is this valuations, which historically have gone back and forth with the U.S. forever, are at a massive discount to what’s going on over in the U.S. How are you feeling over there? What’s the vibe?

Edward: Well, as you say, UK stock market hasn’t really been going anywhere for a while and looks cheap on these traditional valuation measures. Why has it not been doing particularly well? I suppose partly because we didn’t have the, sort of, tech titans. We didn’t have any FANMAGS, or whatever you want to call them, and as you know, the S&P returns have been largely from a small, largely very highly concentrated cohort of top six companies, so we missed out on that. I think perhaps this year we have a bit more energy in the UK index, so with Shell and BP, so that probably helps us. It’s a bit relative

It’s difficult. I don’t have a particularly strong view on why, aside from the imbalance, why the UK market has done so poorly. I don’t think, because unlike Europe, Britain retains its own currency and therefore we can devalue our currency, I guess that should give the stock market a bit more flexibility. I think it may be just at the moment the UK market is a relatively good bet, so you’ll, sort of, come back in 10 years’ time and you probably will find that the UK market has outperformed the U.S. market just on the grounds that it had a lower starting valuation. That’s the argument that GMO would put.

Meb: Well, that’s my guess but I would’ve said that over the last couple years, too, so the valuation, listeners, is probably less than…I think it’s less than half of the U.S.’s now, so take that what for you may. We’ll check back in with Edward in 2032. Sorry, I was trying to do the math. I’m like, “How far away is 10 years from now?” All right, so as we start to wind down here today, anything particularly from the book or topics that we didn’t talk about that you’re like, “You know what, Meb? You must’ve skipped page 212 because was the lynchpin of this book,” or said differently. Doesn’t have to be the book, but what’s got you excited or confused as we look to the future? So either one of those topics feel free to run with.

Edward: Yeah, what we perhaps haven’t discussed at length is my argument that capitalism exists only because there is interest, that capital only has meaning with interest. As I said earlier, you need to discount some future cash flow to arrive at capital value. That’s what capital is. And in my last chapter, I argue that this manipulation of interest is actually bringing about a huge amount of economic malaise, the low productivity growth that follows from the misallocation of capital and the thwarting of creative destruction, but also the inequality that arises. It’s not the good inequality that comes from an entrepreneur founding a business, and creating jobs, and so forth. It’s the bad inequality that is largely accrues to people who haven’t really done that much to earn it. And I argue in the book, I have this chapter on inequality.

Ten years ago, or thereabouts, Thomas Piketty, the Frenchman, wrote this thing saying that, “Inequality happens when the rate of return, r, is greater than the growth rate.” And I said, “No, no, look at it. Inequality occurs when the interest rate, r, is lower than growth.” That’s what we see in the last year, when you inflate asset prices, and those who have assets, or those who work in the financial sector get all the gains, and then particularly the younger generation can’t afford to buy houses. So this sense of capitalism as failing seems to me not due to any inherent problem with a market-based economic system, but because we have been manipulating and tried to almost take away the most important price, the universal price in the capitalist system, the, if you will, lynchpin that holds everything together.

So if the house is supposed to be falling in on itself, it’s not just due to something which is necessary, but it really is a result of our errors. And I suppose if I want this, I think this book should be interesting to people who are interested in investment and investment history. But I also think if you want to understand the problems, or the social and economic problems of the modern day, you need to take to a price what interest is, and what it does, and how necessary it is for us. And you go back to what we were saying earlier, we have a long history of denouncing interest, going back to Aristotle and even earlier. And this book is really saying it’s not in favor of high interest, it’s in favor of fair interest. So a society in equilibrium, an economy that’s growing will have a fair rate of interest, and that is not what we’ve seen really in the last 20-odd years.

Meb: Yeah. As we get ready to release you into the evening, we normally ask the guests, and you can answer this one as you see fit, what has been their most memorable investment? And you as an author who just penned a new book, you can choose to answer that because it could be good, bad, in between, going back to your childhood or going back to yesterday, whatever the timeframe you like. But you could also answer it as, what’s the most memorable or interesting thing you unearthed in writing this book? I’ll let you take it either way or both. If you’re like, “You know what, Meb? I’ve got a damn good answer for both. Let’s go,” either way you want to take that.

Edward: My most memorable investment is I’m friends with a London hedge fund manager, Crispin Odey… I had this, sort of, boozy lunch with him one day. He gave me a stock tip and I came back, it was a leveraged, near-bankrupt nursing home company. And I thought, “Should I buy it for myself?” I said, “No, I don’t know anything about it.” I put 10,000 pounds in my wife’s name and it went up 18 fold. It was taken over six months…wait, wait. It was taken over six months later and all my wife did was complain to me at her huge capital gains tax bill. That I have never forgotten.

Meb: I’ll tell you what, I’ll pay the taxes but you got to give me the capital gains for it. That’s a good trade. Yeah, that’s great. I love it. The stock tips are so funny. I have so many friends that are professional discretionary money managers, and I’m a quant so all that just kind of seems like too much work on my end.

Edward: There is nothing…I’m thinking in terms of, sort of, mea culpa, I didn’t think that Putin was going to invade Ukraine and he did. And I told a friend of mine it didn’t seem like a bad idea if you wanted energy exposure to get it cheap through the Russian stock ETF. And so then he called me up afterwards, said, “It’s down 1/3 after tanks rolled across the border.” I said, “No, it’s cheaper now.” But actually, you see, the point is that when you have an investment thesis, and that maybe that was the investment thesis that Putin wasn’t going to invade, you shouldn’t actually change your mind when that thesis is not borne out and the stock falls. You should probably just get out and think about it again. I don’t know if in 10 years’ time whether I will remember that, but I’ve certainly been beating myself up about it.

Meb: Well, you got the first half of the trade right, the energy part was correct. The Russian part is, I think it’s going to be a TBD as you kind of draw out the future probabilistic outcome. And listeners, this is actually, I think, a little bit of an opportunity, I got to be careful what I say because we manage a few funds, so I’m not referencing our funds. However, most, at least in the United States, mutual funds and ETFs, and this was, like, 95% of all emerging market funds, held Russian securities. Those have been written down to zero. So if you buy an emerging market or a fund, and this isn’t the Russia ETF in particular because that was halted, but funds that have not been halted that have written these down to zero, you essentially have in that portfolio, if they’re trading at net-asset value, which all of them I assume are…

Edward: You’re getting a free option.

Meb: A free call option. Now for some it was only about a percent of the portfolio, but for some it was, like, 10, and so maybe it’s worth nothing.

Edward: GMO Emerging Markets, 15%. These are my old colleagues, GMO Resources Fund, 12%. I know a friend of mine running managing market debt, 15%. So there’s quite a lot of funds in which, you know, by the end of the year, 10% to 15% of NAV was in Russia, now it’s the same amount times 0. I understand you can’t trade them because the U.S. Treasury rules, and I understand. I met some guy the other day who told me that Russians are calling up fund managers saying, “We’re willing to buy this off you.” So there’s definitely something. For me it’s a scandal because we’ve just really, in effect, sanctioned the Western investors. And I think your point is quite right, it’s that if you were seeking an emerging experience, one of the things you should bear in mind, consider, is the free option that some of these funds will have.

Meb: Yeah, and the story will play out. So is it worth zero? Maybe. Is it worth something? Probably. Is it worth par or even more? Well, there obviously something would have to change for that to happen.

Edward: And you know, the great economist who was also a stockbroker and brilliant investor, David Ricardo, one of his sayings…he had two sayings. One was, “Let your profits run,” and the other was, “Never refuse an option.”

Meb: I like both of those. “Let your profits run” is the credo of trend followers everywhere, so I love that one. I’ve definitely quoted it. I’ve never heard the other one but I’ll take it. That’s a great piece of advice. Edward, let’s wind down there. Let’s put a bow on it with that comment. I’d love to have you back in the future when you…the next thing you’re writing or you’ve got something on your brain. Any place people should go if they want to catch up with you on a more often basis? Obviously they need to go buy your new book, but where else should you go?

Edward: Well, I write for “Reuters Breakingviews.” My column, I put it on hold over the summer but I’ll be writing again there from October onward. It’s on the “Reuters” website so you can really see it there, and I do a video with my piece every week. So if you want more of my mug you can get 5, 10 minutes of my interview on each piece, so that’s really the best place to catch me.

Meb: I love it. Listeners, “The Price of Time, the Real Story of Interest.” Check out his book. Edward, thanks so much for joining us today.

Edward: Great, thanks. Good fun. Bye then.

Meb: Podcast listeners, we’ll post show notes to today’s conversation at mebfaber.com/podcast. If you love the show, if you hate it, shoot us feedback at the mebfabershow.com. We love to read the reviews. Please review us on iTunes and subscribe to the show anywhere good podcasts are found. Thanks for listening, friends, and good investing.