You spent countless hours doing due diligence, digging through prospectuses, listening to podcasts, and reading some white papers.

You’ve crafted a plan and implemented a sound asset allocation portfolio reflecting your goals and beliefs. You’ve put the money to work and are now invested.

Many investors now think they are done.

But for however much effort went into the purchase decision, now comes the more challenging part.

Many investors spend countless hours deciding on what investments to buy with their life savings, and then…they just wing it.

The phraseology we often hear from new clients is, “We bought your fund. We’re going to watch it, and we’ll see how it does.”

What does that even mean?

Translation: “If the fund goes up and outperforms in the coming months, we’ll keep it, but if it goes down or underperforms…you’re out.” (The benchmark comparison is never established ahead of time, rather it becomes “whatever is performing well” which for the past 15 years has been the S&P 500.)

Is this the wisest strategy? Is it most likely to help an investor reach their goals? Is it most likely to help a financial advisor serve and retain their clients?

We believe there’s a better way, which has resulted in the Guidebook you’re currently reading.

Think of this as an owner’s manual – not just for Cambria ETFs, but for any of your investments. This Guidebook will discuss how best to view your investments, measure their success, manage them within your portfolio, and recognize when it might be time to sell.

So, without further ado, let’s jump in.

When to sell?

Most of us will not hold our investments until the grave, so when might it be a good time to sell a fund?

We’re going to break this down into three categories: how long to give an investment, dumb reasons to sell, and good reasons to sell.

How long to give an investment.

Okay, you’ve built your ideal portfolio, now what?

History suggests that sometimes doing nothing is the wisest course of action. You let your portfolio take care of itself.

This is why, when it comes to investing, we often say it’s better to be Rip Van Winkle than Nostradamus.

Sadly, most people have a woefully short time horizon when evaluating their results. When they hear Rip Van Winkle the duration they consider is afternoon nap vs. a decade or two.

Investors want their returns and outperformance, the certainty of making the right decision, and they want it NOW!

As the late Charlie Munger said, “It’s waiting that helps you as an investor, and a lot of people just can’t stand to wait. If you didn’t get the deferred-gratification gene, you’ve got to work very hard to overcome that.”

When we asked investors on Twitter how long they would give an underperforming investment, most said a few years at best.

Contrast that with what Professor Ken French said on a recent podcast, where he speculated the amount of time to confidently know if an active investor was generating alpha was…wait for it…

…64 years!

While French’s 64 years is likely too long for you to wait to find out if your approach works, three years is also likely too short.

Here’s French in his own words:

“People are crazy when they try and draw inferences that they do from 3, or 5, or even 10 years on an asset class or any actively managed fund.”

In this age of investment confetti and TikTok investors, the key is to zoom out and expand your investment horizon. But if you deem “10 years” to be an unreasonably long period to judge an investment, just be aware that the shorter your hold period, the more that randomness and luck will influence your returns.

Returning to your investment plan, here’s an example incorporating some humility pertaining to “when to evaluate” to help your future self: “I plan on holding this investment for a minimum of 10 years. Anything less is likely too small of a period to make any rational or educated conclusions about the performance.”

When markets are hitting the fan, this statement will provide some much-needed balance and perspective.

Suppose you buy a new fund, and the strategy has a terrible first year. The pain of regret seeps in, and you say “I KNEW I should have waited to buy that fund. I’m such an idiot. I should probably sell it now before it goes down anymore.”

You pull out your investment plan, you find your Zen, and remind yourself that one year is a lot of noise.

So, first things first, plan to give your investment plenty of years to perform (or not perform) before you pass judgment.

Dumb reasons to sell

While most investors aren’t willing to wait long enough before evaluating their funds, they’re also guilty of another cardinal sin of investing—focusing purely on recent returns when evaluating.

While that might not seem such a sin at first, tell me this…

When looking at performance over just a handful of recent years, how will you know- really know–whether you’re holding a long-term winner or loser?

You see, even if you’ve correctly found a winning investment (or engineered a winning portfolio), the winners also lose much of the time.

In the midst of a painful, potentially prolonged drawdown, how will you determine if your “losing” fund isn’t actually set to make you a significant amount of money in the years ahead?

In the Vanguard paper “Keys to improving the odds of active management success,” the authors examined 552 active funds that beat the market (2000-2014).

94% underperformed in at least five years (about a third of the time). And 50% underperformed in at least seven years (about half the time).

So, even if you pick one of the winners, it will probably underperform in about half of all years. That’s a coin flip! If you know anything about coin flips, you recognize that “heads” could easily show up multiple times in a row.

Even the greatest investor of all time, Warren Buffett, has underperformed the S&P 500 in about a third of all years, including multiple years in a row.

Perhaps the best example of a winning investment appearing as a loser is Amazon.

We’ve all seen the studies illustrating how just a few bucks invested in Amazon back in 2000 would be worth a gazillion dollars today. But the reality is that just about no active investor would have been able to hold that long.

This is because Amazon suffered a handful of gut-wrenching 50%+ drawdowns over the years – one of which was a 90%+ collapse. Here’s a fun graphic illustrating some big drawdowns from the famous Bessembinder study.

If you’re prone to fiddle in your portfolio, and your main way of evaluation is performance, would you have had the foresight and discipline to stick with Amazon during that bloodbath?

The reality is that even great stocks and/or funds can go through long periods of horrendous market performance and yet still succeed.

It’s important to consider selling criteria ahead of time for the investments that perform poorly (though making such a conclusion requires sufficient time, as we pointed out earlier) but also for your investments that perform well.

We often joke that investors have told us the following, “Hey, I bought your fund, and it underperformed the benchmark by more than it should, so I’m selling it.”

You know what we’ve never heard even once? “Hey, I bought your fund, and it outperformed the benchmark by more than it should, so I’m selling it.”

Theoretically, both would be disqualifiers, but in only one scenario, people sell.

Many investors become emotionally attached to investments that have performed well and extrapolate that performance into the indefinite future. This is usually a very bad idea.

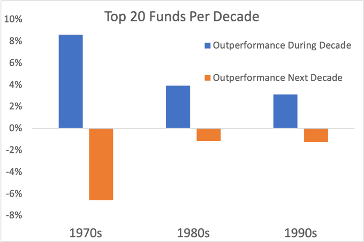

The late great John Bogle would track the top 20 investment funds per decade that outperformed, then track those outperformers into the following decade. In every decade, the highfliers crashed back to earth and became big losers and underperformers in the ensuing decade.

As Bogle once counseled, “Don’t just do something, stand there!”

Source: Bogle

Clearly, we want to avoid highfliers that crash back to earth.

Let’s be clear, the professionals are not much better at this.

Goyal and Wahal wrote a paper examining 8,775 hiring and firing decisions but 3,417 plan sponsors delegating $627 billion in assets. What did they find? Professional managers chased performance, and on average they would have been better off staying with their old manager instead of the shiny new one.

So, if all that you’re evaluating is recent returns, watch out.

The Wise Way to Evaluate Your Investment and/or Overall Portfolio

So, if performance alone (specifically, too short of a window of performance) isn’t a good way to evaluate a fund, what is?

Here are a few potential ways to evaluate (and potentially consider selling) your fund…

- The assets of an existing fund strategy are becoming too large to implement effectively within a fund structure.

- Your goals have changed (perhaps you have a new grandchild or some unexpected health concerns).

- The thesis for why you invested has not played out.

- The fund manager retires, or the strategy experiences style drift.

- Legal or structural tax changes have made the strategy less attractive.

- A new strategy offers superior diversification to your current portfolio lineup.

- Your fund may increase its expense ratio and/or all-in fees, and cheaper, more tax-efficient choices are readily available.

All are justifiable criteria to evaluate a fund, as well as examples of valid reasons to sell. Make sure you include this as part of your written plan.

As you write down your reasons for evaluating and selling an investment, try and be honest with yourself. Richard P. Feynman said. “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool.”

The key question is, are you chasing performance or implementing a valid sell decision?

Assuming you answered the latter, let’s move on…

What advice do we offer investors during tough times?

Be Your Own Best Friend

On the podcast, we often ask the guests, “What was your most memorable investment?” Often, the answer is a very painful investment that went south or perhaps a big winner that evaporated.

Old traders have had enough losers and bad decisions to fill volumes of trading journals.

One of our favorite investment quotes from Bill Duhamel is “Every trade makes you richer, or wiser. Never both.”

Considering this reality, we’d like to conclude this article with an important note on the entire process. Be kind to yourself.

If you’re paralyzed by a “to sell, or not to sell?” decision, our favorite “algorithm” is to go halfsies. In other words, sell (or buy) a half position rather than a full position. By doing this, you diversify your possible outcomes, which helps avoid regret —a significant emotional burden.

This halfsies approach can manifest in different ways…

If you can’t decide which fund to buy out of two, buy both, but with smaller position sizes. If you can’t decide whether to sell your position, begin selling smaller portions of your position spread equally across the next 12 months. Or, want to buy something, but are nervous about that lofty valuation? Begin purchasing a small lot today, and be prepared to expand your holdings over time. But again, try to write down your process and rationale beforehand.

In short, stop viewing your investment decisions as binary “black or white.” You can dip your toe in or out of the water. Just don’t use this concept to deviate too far from your process!

Welcome to the Family

Effectively navigating the market’s ups and downs, as well as the inevitable under- and over-performance of your specific investments, can be incredibly challenging.

But with deliberate thought, foresight, and planning, you can overcome those challenges with a balanced portfolio that helps you reach your financial goals – and, as importantly, enables you to avoid sleepless nights filled with “what should I do?” questions.

This brief article aims to help you consider key issues that impact your portfolio performance, wealth, and overall confidence as you engage with the markets.

Thanks, and good investing!