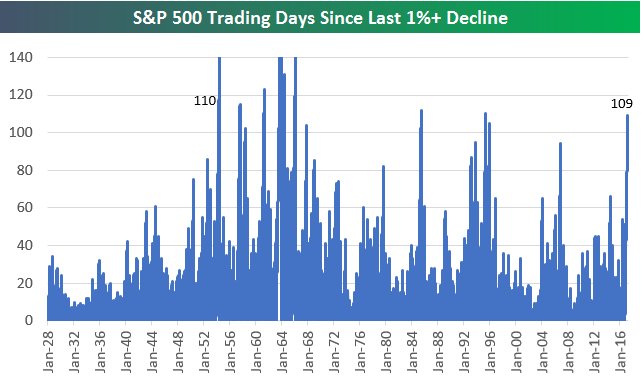

As I’m writing this, the S&P has just closed more than 1% lower for the first time since last October. The streak of 109 trading days without a 1% decline is one of the longest in history.

Chart via Bespoke

The bears who have been getting pummeled over the last eight years are suddenly rumbling back to life. That makes this article, which I’ve been drafting over the past couple days, even more timely.

If you’re an investment advisor watching the sell-off, you might be feeling especially nervous right now – even more so than a retail investor.

Why?

Well, negative stock market moves have a leveraged, intensified effect on asset managers and financial advisors…far more than many realize.

Advisors have exposure to the stock market through:

- Their personal portfolio – obviously, a bear market will erode the value of the advisor’s own portfolio.

- Their shorter-term business revenue (i.e. client portfolios) – a bear market will decrease the size the advisor’s total book (client market cap), resulting in less revenue spun off from the smaller asset base.

- Their longer-term business revenue – lengthier bear markets will result in some clients panicking and withdrawing their investments entirely, which could permanently shrink the advisor’s book.

- If the advisor is an employee of a parent company, he/she risks potential employment termination due to downsizing.

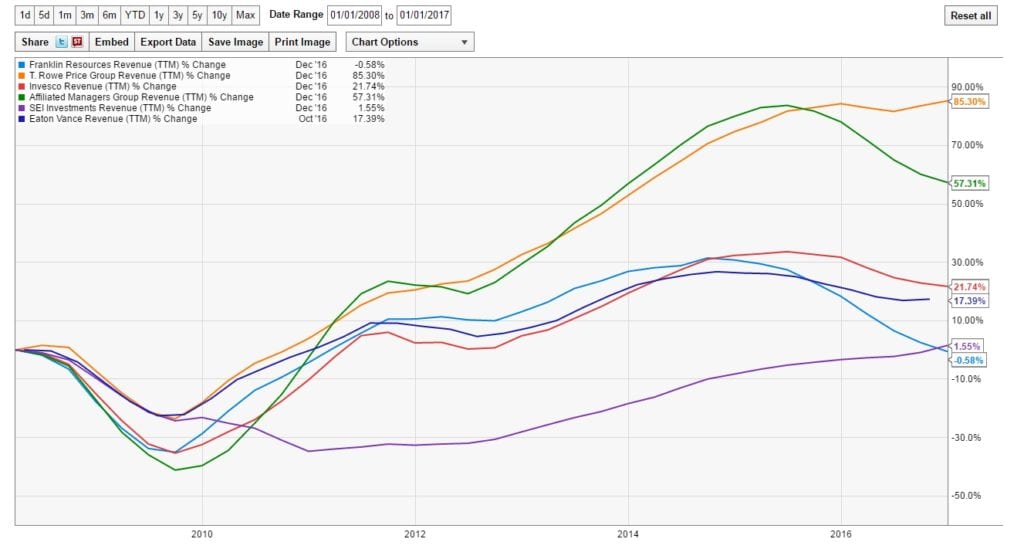

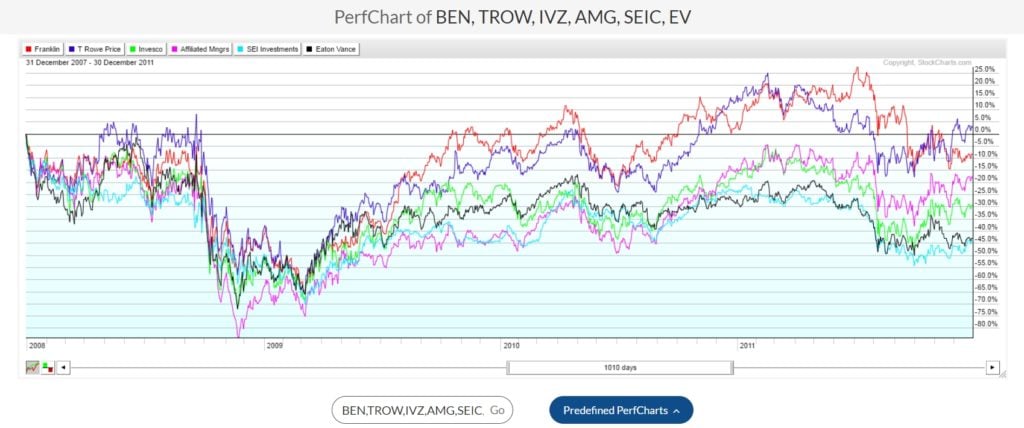

You can view some of the correlated effects in the two charts below. They highlight the revenues (chart 1) and stock prices (chart 2) of five, publicly traded asset managers.

Revenue in the global financial crisis declines across the board… (click to enlarge)

And not surprisingly, their stocks take a hit… (click to enlarge)

Ok, so bear markets can hammer both investments and business revenues, often amplified by clients panicking and pulling out assets. Many advisors reading this may respond, “Yeah, thanks, Meb, I’m already well aware of my situation. The question is what to do about it.”

Fair enough.

We’ve chatted about this before in a couple old blog posts, “How To Hedge Your Business” and “”Why Don’t Asset Management Companies Hedge Their Biggest Risk?”

The suggestion in those posts is even more timely right now. I’m going to draw your attention to four caution signs the market is flashing, which makes having this awareness even more important. Then we’ll discuss how you can be more intentional about protecting your portfolio and business starting today. Let’s jump in.

1. An Aging Bull

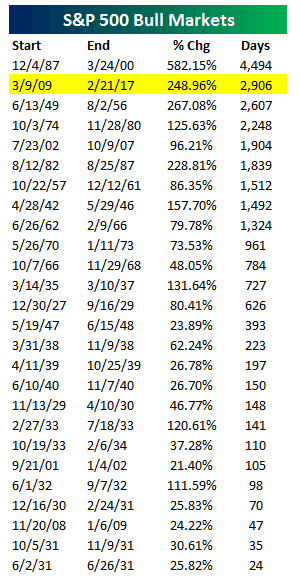

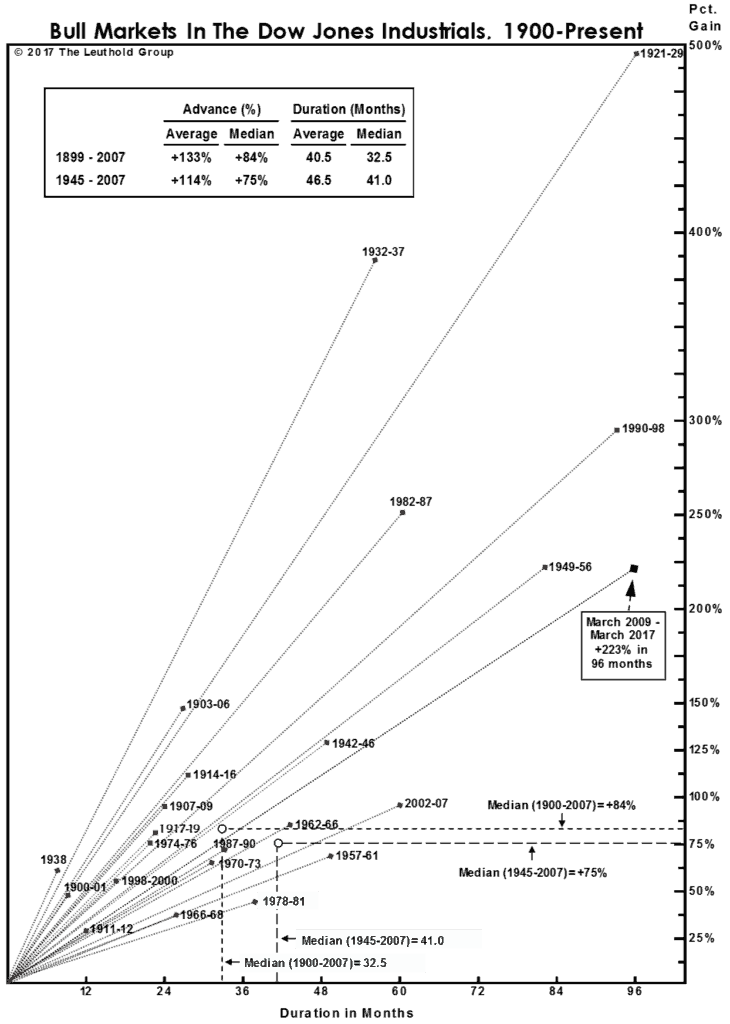

Our current bull market began on March 9th, 2009.

It just turned eight years old, which makes it the second longest bull market on record. In fact, it’s 78% longer than average bull market length of 54 months.

Below is a chart from our friends at Bespoke identifying all bull markets since about 1930 (data updated 2/22/17):

And now we have THE longest Dow bull market ever, according to Leuthold. Not the biggest of course, but the longest:

So, though obvious, the first caution-sign is simply this bull’s venerable, old age.

We don’t need to belabor this point, but throwing new capital into a bull market that’s already the first or second-longest in history would seem unwise. It feels a bit like being on mile 21 of a marathon…and suddenly agreeing to start and complete a new, second marathon as soon as you finish the one you’re currently running.

2. Elevated Valuations

In simplest terms, the stock market is overvalued.

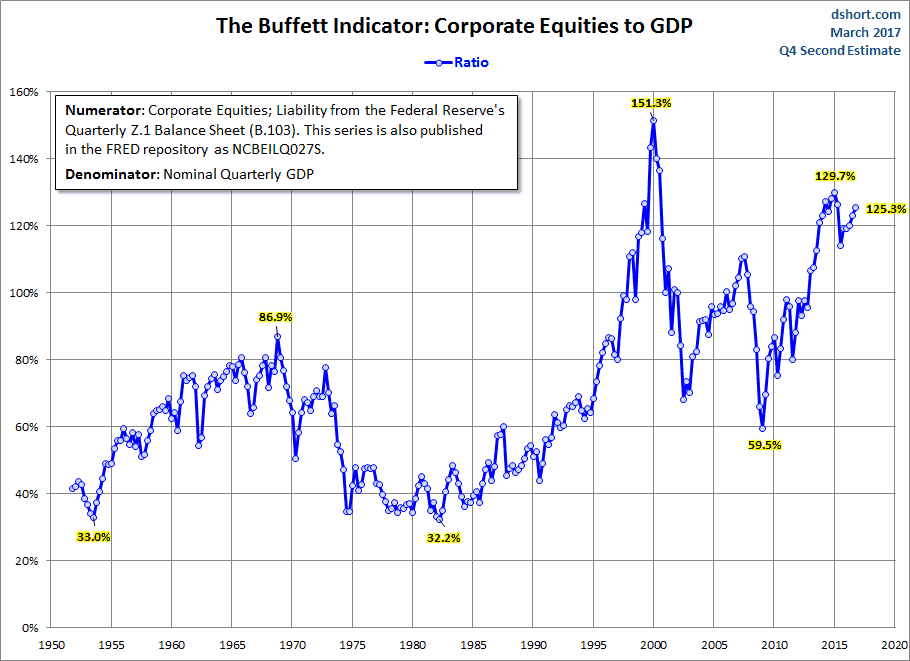

Below is the respected “Buffett Valuation” (based on Warran Buffett’s fondness for this metric, calling it “probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment”). It compares the total value of the stock market to a country’s GDP.

Right now, the U.S. Buffett valuation is about 1.3, meaning the stock market is about 30% larger than the entire U.S. economy. Historically, markets start getting in trouble when this ratio passes 1.0. And if you’re wondering, the ratio hit a top of around 1.1 before the 2008 crash.

Chart via DShort:

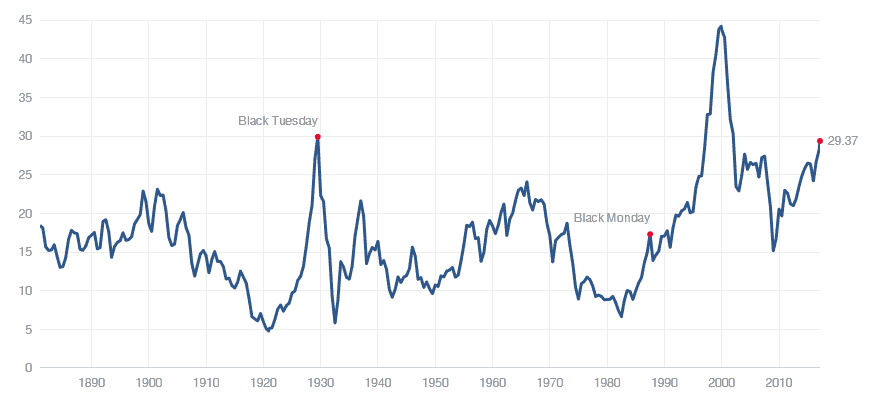

For another example, here’s my favorite Shiller 10-year PE (CAPE) ratio.

Chart via Multpl:

Note that we’re at the highest valuation we’ve seen since the record-highs in the 2000 crash. And for any Shiller-detractors, don’t miss the main point – pick a basket of your own favorite valuation metrics, and collectively, they’ll provide you the same “overvalued” takeaway. We could argue over how accurately any single, specific valuation metric approximates by how much, but that would be largely irrelevant; if you look at a basket of common valuation metrics – things like price-to-earnings, price-to-book, price-to-free-cash-flow, and so on – they’re all generally saying the same thing: The market is expensive.

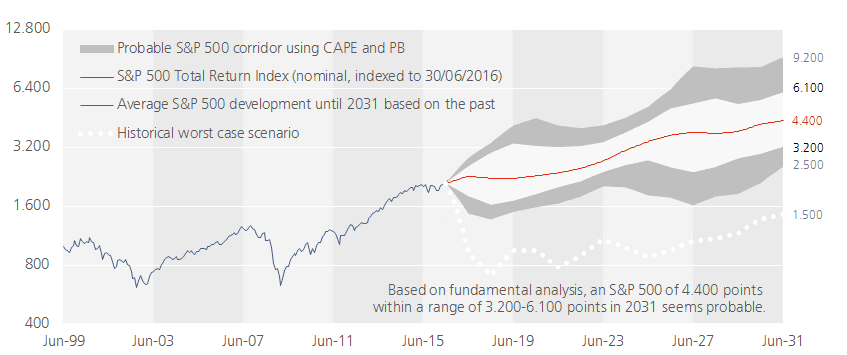

Here is a nice description from the good folks at Star Capital – I like how they describe the future as a spectrum of possibilities:

In a past blog, we compared where we are in the market today to a blackjack player in Vegas, sitting on 16 vs. a dealer’s 10 upcard. Sure, he could could take a card and receive a 4 or 5, get incredibly lucky,hit 20 or 21. But odds are,he’s going to bust his hand.

Similarly, betting on significantly higher valuations from this point carries significant risk. It doesn’t mean you might not get lucky and get those greater gains, but if we go by the odds, it’s not your safest bet. We track a basket of long term valuation metrics over on The Idea Farm, and the U.S. is the second most expensive market in the world. Getting dealt that 5 right now would require you to be very, very lucky.

So, one answer, of course, is to place at least half of your equity allocation in foreign stocks (which no one does), and preferably, more than that with exposures to the really cheap countries.

For perspective, the cheapest 25% of countries have a CAPE of 10, Foreign Emerging (14), Foreign Developed (16), and the US (30). But I’ve talked about the CAPE ratio and home country bias enough on this blog so we’ll move on.

3. Sentiment

Then there’s investor sentiment…

When everyone is loving the stock market and convinced it’s going higher, it’s often an unwise time to be investing new capital. There are several different investor sentiment indicators suggesting investors are more bullish than ever, but I’ll just draw your attention to a recent Meb Faber Show podcast with Doug Ramsey from Leuthold. In it, Doug told us that this is the most optimistic sentiment he’s seen in the last eight years. Remember Warren Buffett’s adage: “Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.”

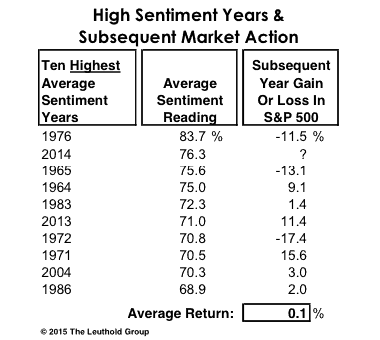

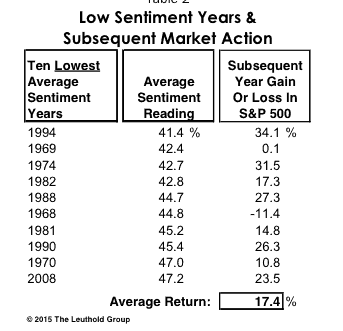

The Investors Intelligence survey recently hit 63.1 – the highest bullish reading since 1987. Leuthold showed in this old post that the high sentiment years are followed by low returns, and vice versa (bulls as % of bulls and bears):

(Oddly enough, the AAII sentiment surveys are not showing extreme bullishness yet.)

4. Where’s the Volatility?

To illustrate our fourth and last red flag, let’s borrow a popular cliché from Hollywood…

“It’s quiet. Almost too quiet.”

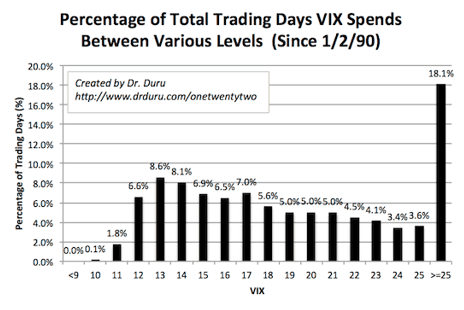

To make sure we’re all on the same page, the most common measure of volatility is “the VIX.” VIX is the symbol for the Chicago Board Option Exchange’s Volatility Index. Without getting into too much detail, it’s a measure of expected stock market volatility over the short term (ensuing 30 days).

The general line in the sand separating calm markets from fearful markets is a VIX reading of 20. At the end of January, the VIX dropped below 10 for the first time in a decade.

Even the Fed is concerned. The Fed minutes from the January report to Congress read, “They also expressed concern that the low level of implied volatility in equity markets appeared inconsistent with the considerable uncertainty attending the outlook for such policy initiatives.”

For some added context, here’s a 10-year chart of the VIX from Yahoo. As I write, our level is 11.3.

And for further context, here’s a table from Investing.com showing the percentage of time the market spends at various VIX levels.

Now, low volatility does not mean a market blowup tomorrow. We could remain in a low-VIX market for a long time. However, this anemic VIX is another brushstroke painting the broader image of a market that we believe is flashing more red than green.

So What Then?

First, to avoid any hate mail, please understand I’m not declaring an imminent market crash based on these four red flags. We all know markets can keep climbing far past the point logic would suggest otherwise. I’m simply suggesting that this is all cause for caution, and seems to imply this bull’s better days are behind us.

You don’t have to look hard to find reasons to be cautious of the markets right now. But what’s the answer? Pulling your money out and shoving it under the mattress isn’t a logical response. So what then? What can investors do now to protect themselves?

Well, you buy car insurance to protect your car, right? And home insurance for a fallen tree or a break-in? Ditto for life insurance as a protection for your family.

Well, do you apply the same logic to your portfolio?

This question leaves many investors scratching their heads.

Portfolio protection can take many forms. In its simplest implementation, it could be basic portfolio diversification – trimming your exposure to U.S. equities in favor of, say, cheap foreign market equities. Or adding real assets such as TIPs, commodities, and real estate. Or many investors prefer the safety of government bonds, which historically has been a great diversifier during bad times in stocks (though with interest rates as low as they are, are they a guaranteed hedge? No).

For your book of business, spending time educating clients to adjust to lower return expectations is a necessary step to prevent bad behavior and withdrawals during the next bear.

My personal favorite “insurance” is a trend following and/or managed futures strategy. As I’ve written a great deal on trend following in numerous other white papers and posts, I won’t get into more specifics right now.

Another option – you could buy puts, either on equities you own, or on a broader index such as the S&P 500. The idea is that if the market (or your stocks) rolls over, these puts will enable you to either sell your equities at the pre-determined strike price (play defense), or if you bought puts on an index, you’ll be able to profit as the index falls (play offense).

Interestingly enough, many times this insurance idea doesn’t catch on with investors (retail and advisor alike). In large part, the reason is cost. Yes, you’re coming out of pocket to buy this insurance, usually in the form of put options; and if the market doesn’t move in such a way that capitalizes on your insurance, then most times that money is gone, and you have to pony up gain for more insurance going forward.

Investors don’t like this idea, and for good reason – in stable markets, this cash outlay is a drag on returns. But this is exactly what you do with your car, home, and life insurance premiums. Each month you pay into your policy – which is a drag on your household savings – yet odds are, you’re happy when nothing happens to require a claim.

Why should it be different with your investment portfolio?

On the other hand, what if you pay for an insurance strategy and you’re covered during a tail market event? Let’s see…

What Portfolio Protection Can Do

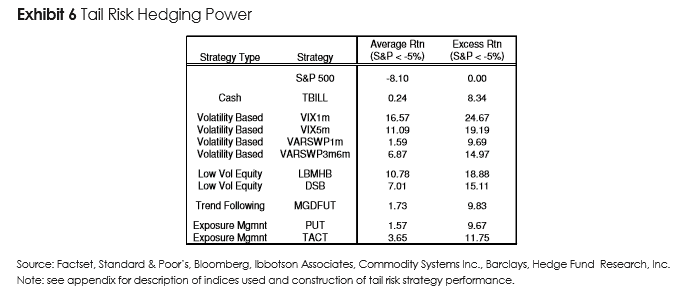

The table below comes from a report called “A Comparison of Tail Risk Protection Strategies in the U.S. Market.” I encourage you to read it. But as it’s a deeper dive into this world, I’ll only get into it briefly here.

What I want to draw your attention to is a comparison of market returns during times of tail events. Specifically, the report compares S&P 500 returns to those of several different tail risk strategies during crisis months between March 1990 and March 2011.

According to the report, “In these months, the average return for the S&P 500 is -8.10% while average return to all of the tail risk strategies is positive.” The chart below provides more color.

This chart is the reason why investors who “pay up for insurance” tend to find the cost more than worth it during volatile, tail markets.

What Now?

So what do you do with this?

First, I’ll remind you again that I’m not calling a market top here, or claiming we’re at the edge of a precipitous market drop.

On the other hand, numerous signs suggest this market is running long in the tooth. So, the question really becomes: What will you do now to protect your portfolio?

This question takes on added gravitas if you’re an investment advisor. Not only are you facing your own portfolio risk, but however you decide to position your clients carries with it professional risk as well. Choose correctly, and you’re a hero. If the markets go against you, well…

Regardless of whether you’re a retail investor or advisor, you face the same choice: On one hand, you can do nothing with your portfolio at this point, keeping those “insurance premium dollars” in your pocket while banking on continued gains.

On the other hand, you could buy some form of tail risk insurance. Sure, the market may continue to climb higher, and you might have to continue paying these insurance “premiums” for a while – possibly far longer than you want to.

But the question is “will that out-of-pocket cost be worth it at whatever point the market eventually suffers a significant drawdown?” We can’t say when that will happen, but we know it will at some point.

So what’s right for you? For me, adding some insurance positions to my portfolio makes sense at this point.

Whether or not you agree, I suggest you at least take a moment to stop whatever you’re doing, focus on this tradeoff, and then be intentional about your decision – whether for or against.

Who knows? Some quarters or years down the road, you might find this 5 minutes of thinking made all the difference.