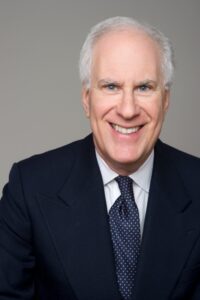

Guest: Marc Chaikin is a 50-year Wall Street veteran who founded Chaikin Analytics LLC to deliver proven stock analytics to investors and traders.

Date Recorded: 3/23/2022 | Run-Time: 36:42

Summary: In today’s episode, we start by discussing Marc’s early career and what led him to have an approach today that combines both fundamentals and technicals. We hear about some of the 20 factors that make up his model and how it urged him to buy Overstock and Wayfair early in the pandemic. Then, Marc walks us through what industries he’s bullish on today, including energy, financials, and aerospace and defense.

Sponsor: Masterworks is the first platform for buying and selling shares representing an investment in iconic artworks. Build a diversified portfolio of iconic works of art curated by our industry-leading research team. Visit masterworks.io/meb to skip their wait list.

Comments or suggestions? Interested in sponsoring an episode? Email us colby@cambriainvestments.com

Links from the Episode:

- 0:39 – Sponsor: Masterworks

- 1:54 – Intro

- 2:33 – Welcome to our guest, Marc Chaikin

- 4:12 – What led Marc to combine fundamentals and technicals

- 10:53 – Marc’s decision to launch Chaikin Analytics

- 19:04 – Examples of when the model has surprised Marc

- 22:12 – Marc’s thoughts on the market today

- 28:25 – Investment beliefs that Marc feels other investors should consider

- 31:33 – Marc’s most memorable investment

- 33:25 – Learn more about Marc; chaikinanalytics.com

Transcript of Episode 407:

Welcome Message: Welcome to the “Meb Faber Show,” where the focus is on helping you grow and preserve your wealth. Join us as we discuss the craft of investing and uncover new and profitable ideas, all to help you grow wealthier and wiser. Better investing starts here.

Disclaimer: Meb Faber is the co-founder and chief investment officer at Cambria Investment Management. Due to industry regulations, he will not discuss any of Cambria’s funds on this podcast. All opinions expressed by podcast participants are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of Cambria Investment Management or its affiliates. For more information, visit cambriainvestments.com.

Sponsor Message: And now a quick word from our sponsor. We’ve seen a lot so far in 2022, the highest inflation print since 1982, Russia invading Ukraine, and Facebook had the largest one-day drop in value in U.S. stock market history, over $200 billion. And something else important just happened. The U.S. stock market just moved into a new regime, expensive and in a downtrend. Historically, that’s not been a warm and fuzzy place. Potentially means higher volatility and drawdowns to come. So, let me ask you this, is your portfolio ready for 2022? If not, you may want to consider investing in alternative assets, and there’s one that’s gained a lot of attention lately, blue-chip art. It’s one way I diversify my portfolio. After all, blue-chip art typically has a low correlation to stock market. Diversifying with art, though, isn’t a new concept. Some of history’s greatest titans like J.P. Morgan, the Rockefellers, both invested in art. With Masterworks, you can too. This FinTech unicorn is the app turning multimillion-dollar paintings into investible securitized products. And my good friends at Masterworks are giving you a special deal. You can get VIP access to become a member, just go to masterworks.io/meb. That’s masterworks.io/meb. See important regulation A disclosures at masterworks.io/cd. And now, back to the show.

Meb: What’s up you all? We have an awesome show for you today with a true legend of the industry. Our guest is Marc Chaikin, a 50-year Wall Street vet and the founder of Chaikin Analytics. In today’s episode, we start by discussing Marc’s early career and what led him to have an approach today that combines both fundamentals and technicals. We hear about some of the 20 plus factors that make up his model and how it urged him to buy overstock in Wayfair early in the pandemic. Then Marc walks us through what industries he’s bullish on today, including energy, financials, and aerospace and defense. Please enjoy this episode with Chaikin Analytics’ Marc Chaikin. Marc, welcome to the show.

Marc: Meb, it’s good to be with you.

Meb: Many listeners will be familiar with your name, and we’re going to talk about all sorts of fun stuff today. I want to rewind because you started in Wall Street in a time really before the widespread adoption of computers and quants and everything else. Tell me a little bit about your origin story. How did you get started in this crazy biz of ours?

Marc: So, it really is crazy these days with all this volatility. I actually got registered as a stockbroker the day the bear market of 1966 ended, October 7th, 1966. For the first two and a half years of my career, every day seemed like an uptick. And then the first bear market I ever encountered in 1969, ’70 reared its ugly head and I quickly realized that fundamental research was not going to cut it in a bear market. I was with a really fine research firm named Shearson, Hammill at their main office at 14 Wall Street. I got to know the analysts really well and the market strategists and those relationships worked great as the market was going up to new highs. But pretty quickly I realized that analysts put their feet in cement just like individual investors do. And by that I mean they get stubborn about their picks and double down as stocks are falling and finally near the bottom of the bear market, they throw their hands up and throw in the towel and tell you to sell. So, I began what turned into a lifelong pursuit of technical analysis as a way to supplement fundamental research.

Meb: And so, one of the beauties of technical analysis to me is studying a lot of the history of technicians. I think a lot of people today will cite academic literature from way back in the 1990s when a lot of the academics were talking about some of the features, but then you look back on the popular literature in books and papers that goes back to the ’50s and ’60s. And some, the Charles Dow stuff, goes back quite a bit further. Were there any particular influences in that period that you thought really stood out or that you still think have some merit today?

Marc: Actually, two influences really stand out. One was a fellow named George Chestnut who ran a mutual fund called American Investors out of Greenwich, Connecticut. I got introduced to him by an associate, a broker who really knew a lot about investing. And George Chestnut ran his mutual fund based on industry group relative strength. He looked for the strongest stocks and the strongest industry groups. And we’re talking about the mid-’50s where he was doing his work at the kitchen table. And I liked that approach so much that I actually invested my son’s money in those two funds when they were born, and that fund was up 300% over 10 years. Now, fast-forward to 1968 and a guy named Bob Levy published his PhD thesis. We had a bookstore downstairs from my office called “Doubleday Wall Street.” I bought the book and it really changed my life because I became a firm believer that relative strength combined with fundamental analysis is really the key to successful investing.

Meb: There are obviously reams and reams and reams of evidence today. At that time, there was some, but a little more anecdotal. What was the reception as you sort of like talked to bankers, as you talked to people about this concept of thinking about fundamentals, thinking about technicals combined, particularly relative strength? Was that something people were receptive to, or did you sort of have to massage the narrative in a way that different groups would embrace different parts of that discussion?

Marc: So, that’s an interesting question because I was in the main office of Shearson, Hammill which had a big investment banking department. And they periodically walked the investment banking clients through what we called our boardroom back then. And our branch manager, who was a real company guy, said, “Hey, any of you who are using charts, don’t you dare keep them on the desk. Put them in the drawer because we’re a fundamentally-oriented brokerage firm and technical analysis has no place in all this.” So, I basically kept it sub-Rosa. But what I did do was to validate Bob Levy’s research. That really gave me the confidence to use this in conjunction with fundamental research, but I never really talked about it with clients.

Meb: So, you kind of just like were the brilliant scientist behind the…they said, “Marc just got these great stock picks. He doesn’t know where they’re coming from. He just keeps coming up with these great ideas.” Give us the evolution. All right. So the ’60s, the ’70s you had the change to the romping bull market of the ’80s. ’70s was a really tough time, but ’80s and ’90s began this upward march of markets. Where were you during the period? And was this an evolution of some of the ideas that you now have formulated today?

Marc: Let’s go back to the ’70s, Meb, because that’s when I learned that it’s the stocks you don’t own that matter. Now, what do I mean by that? It’s the stocks you avoid because they have weak technicals and/or weak fundamentals that really make a difference because losses are hard to make up, as you very well know. If the stock is down 50%, it’s got to go up 100% for you to get to even. It’s even worse than a bear market when stocks drop 80% to 90%. It’s really hard to get your capital back. But probably the most important thing that happened to me in the 1980s is that I joined Drexel Burnham Lambert, which was famous for its junk bond department. They also had a quantitative department run by a guy named George Douglas. George was a quant and he had a database called … He was the original researcher in what’s called earning surprise and earnings estimate revision. George not only mentored me but he gave me access to his database. I was the only retail stockbroker at Drexel who had access to it.

The reason that’s important is it gave me the ability to combine my relative strength research with the … earning surprise and earnings estimate revision database and all the other quant data points that he had like insider trading. And what George taught me back in the ’80s which still works today is that analyst estimate revisions are the single biggest short-term driver of stock price movements. And that’s true today, even with high frequency trading and all the information that’s available on the Internet, every average investor, as well as institutions. There’s a virtuous circle between companies that exceed Wall Street estimates or disappoint and how analysts react to them. Analysts react by either raising or lowering their estimates, and believe it or not, 35 years later, that still matters to institutional investors. So, I was able to take my research to another level and combine fundamentals, technicals, and earnings estimate revisions and earnings surprise. That gave me the confidence to go off and start an institutional brokerage firm in 1989 with a partner from Philadelphia.

Meb: And if I recall, you ran that for a while and ended up selling it. Is that the right ending on that chapter?

Marc: It is, Meb. We were very fortunate. It was a great run for six years working with institutional clients, people like Steve Cohen when he left … to start his famous hedge fund. We became his second call. He called Reuters first and he called Bloomberg and he called Chaikin. And he used the research and analytics terminal to very successfully build a multi-billion dollar hedge fund. So, it was a really good time. And it also enabled me to build a research department within Instinet. We built a five-person quantitative research department, and we did a lot of work combining fundamentals and technicals because our mission was to show portfolio managers how to use technical analysis in their decision-making process. So, this really got me started on the whole quantitative analysis path.

Meb: Walk us through that because I’ve heard the story, but you said, “You know what? I’ve had enough of this Wall Street. It’s crazy. I’m going to enjoy a little sabbatical,” but just like in “Godfather”, he says, “He just keeps bringing me back in.” You got back in the game. Tell us what the decision to come back and launch some of your new offerings was.

Marc: I like to say that I flunked retirement. Basically, I was trading and building systems for some institutional clients, but 2008 was a game-changer for me. I had connected with an old girlfriend from Philadelphia and we were now married and living in Connecticut. Actually, we’re back there now after a 15-year hiatus in Philadelphia. But my wife, Sandy, was in the marketing business and self-employed and she had a 401(k) plan. And she picked some big winners. But as her business grew, she was marketing country inns in New England. She really didn’t have the time to manage her money. Even picking and choosing mutual funds was more than she wanted to do. So, she hired an investment advisor. And so, at some point in the fall of 2008, she said, “You know, Marc, there’s got to be a better way. I’ve been calling my advisor. Most of the time he doesn’t take my calls. When he does, he says, ‘Just sit tight.'” And interestingly, Meb, his idea of diversification was to take her out of her two very terrific performing mutual funds and put her into a diverse portfolio of 10 funds but in a bear market. That wasn’t diversification. It was just noise.

So, she said, “There’s got to be a better way, but I really want to close this account down and I don’t know what to do with my money.” I said, “Well, the first thing to realize is you can’t get out of the market because if you do that, you’re not going to get back in in time to benefit when this bear market is over, and it will be over. They always end. Never been a bear market in 100 years that didn’t end. Sometimes badly, but always there’s a new beginning.” And she said, “Well, what do I do with my money?” But I said, “I’m going to come out of retirement and we’re going to start a company. You can do the marketing. I’ll do the research because there are so many people in your position, people who’ve taken back control of their investments.” Actually, these people are known as self-directed investors. They don’t have the tools or the temperament to manage these hundreds of billions of dollars because that one was coming out of full-service brokerage firms at the time. So, in a one-year research project, I basically fulfilled my life’s dream by building a model that combined both fundamentals and technicals, and that model became known as the Chaikin Power Gauge rating. I call it a quantamental model. It takes 20 factors grouped into 4 components to get the power gauge rating.

Meb: So, I’m looking at these and these will sound familiar to a lot of investors. You got the financials group with things like return on equity and free cash flow. You got the earn earnings group with earnings growth, earnings surprise which you mentioned earlier, earnings consistency, technicals. You got relative strength versus the market, the Chaikin money flow, and experts group, which includes things that a lot of people have been talking about in the last year like short interest and insider activity, industry relative strength. Walk us through sort of, A, the process of putting together this recipe because as quants and market participants, we love to fiddle and it’s like endlessly deep rabbit hole. Like we could spend, you know, years and months working on ideas behind finalizing a model. But take us behind the chef decision on how you kind of decided to put this all together in the way you did.

Marc: The key thing to realize is we lock down the model and the weights because not all the factors are weighted equally. So, for instance, if you’re looking at the financial metrics, you’re talking about a 35% weight in the model, and the two biggest weights within financial metrics are price to sales and free cash flow to market cap. And I think experts are our secret sauce. They’re 30% of the model, and you don’t find these factors in the typical quant model. The key is that we locked down the model and actually just made some changes in the last year, 10 years later, but the factors are all the same. Basically, the model has been locked down and performing extremely well since 2011.

Meb: As you look at it, talk to us a little bit about how you guys offer this. I know it’s the basics for some indexes, but also you guys have an app, a web portal that allows you to kind of run any stock through the power gauge numbers. Give us an overview of how people can access and then utilize some of this research for their own investing.

Marc: Right now, because we became part of MarketWise and Stansberry Research a little over a year ago, our primary focus is newsletters. We have a suite of monthly newsletters. Some of them are very affordable for investors who just want to get my take on where the opportunities lie in the stock market based on the power gauge and looking at some pretty well-known stocks. And then we have more opportunistic newsletters that enable people to get the benefit of this top-down approach that I’ve been using for over 30 years where we look for strong stocks in strong industry groups, again, building on what George Chestnut and Bob Levy discovered in their research.

And also, this approach tells me what stocks to avoid. It’s really the stocks you don’t own that matter at the end of the year, avoiding those one or two big losses that can undermine your portfolio performance and your confidence. And then we have our high-end terminal power gauge ratings, meaning that our model is positive and strong fundamentals or alternatively, using it as a filter on whatever research they depend on, whether it’s Morgan Stanley, Jim Cramer on TV or their own research on the internet. So, the power gauge rating is proven to be a really effective overlay on any research.

Meb: What’s like the distribution of the ratings? Does this go from…? I like it because it’s like an accelerator. What’s the right phrase used for this? It’s like a gauge. It goes from neutral or positive, but, like, how do people think about it? Is there a certain threshold? Is like, “Hey, you should be buying in the top 25% and then selling when it goes below 50%,” or, like, how do you kind of tell people to utilize this concept?

Marc: Power gauge varies from very bearish to very bullish. There are actually seven silos or buckets that are equal size. We rank 4,000 stocks. So, you start with the fundamentals because I’ve always believed that fundamentals drive the market, going back to the day I started investment business back in 1966. And then I want the market to validate my research, in this case, our quant model. The theory is no matter how good your research is, whether it’s fundamental or quantitative, if the market doesn’t agree with you, Meb, guess who wins? The market always wins. So, I like to overlay relative strength on top of our fundamental ratings. And we’ve got a proprietary way to look at relative strength that can be very visual as a way to confirm what our quant model is saying, and it helps me avoid bottom fishing. I’ve been quoted as saying bottom fishing is the most expensive sport in America. And then our third piece of the puzzle, Chaikin money flow, which is on every Bloomberg and Reuters terminal in the world and on everyone’s online investing platform. In fact, it’s also on online sites like stockcharts.com based on the premise that the big investment banks, the biggest hedge funds move the market, they do their research, so we want to know if they’re accumulating a stock or if they’re selling it on strength, and that’s reflected in Chaikin money flow, which has actually proven itself over 40 years.

Meb: One of the challenges I think for a lot of people on managing quantitative rules-based portfolios, they like to tinker. And so, personally, I remember looking back in my early days of being a quant and running some screens or something and it’ll kick out some names and I’d be like, “Oh, God. I don’t want to buy that stock. Oh, no.” If there are any times where you’ve been surprised at kind of what this kicks out or areas where you kind of scratch your head and say, “Oh, that’s interesting. The model is really bullish on this or bearish on that,” and that goes against either the consensus of what a lot of market participants are positioned right now or the way that stock has been performing? Anything kind of stand out?

Marc: Very definitely, Meb. And it goes back to the sort of lockdowns we experienced during the COVID crisis. I’ve always been a believer that you have to be flexible. And as I said earlier, you can’t put your feet in cement in the stock market. That’s why I love relative strength because the market will always tell you what you should be thinking instead of you telling the market. So, going back to March and April of 2020, most of us, my wife, Sandy, and I had just moved from Philadelphia back to rural Connecticut, sort of farm country, and we were decorating our house. We had a porch that we didn’t have in Philadelphia, so we needed furniture. We weren’t going out to shop in malls because they were closed. And about that same time, overstock.com popped up on our system with a bullish rating. I said to my wife, Sandy, “This is weird. Here is a stock that I really don’t like from a management point of view and suddenly it’s got a bullish rating in the middle of a lockdown.” She said, “Well, guess what, Marc? We just bought our porch furniture from overstock.com.” I said, “We did?” She said, “Yes.” And so, there’s a good example where I never would have bought the stock without the power gauge rating.

Now, fast forward a month or two and the power gauge rating, by the way, overstock.com went from 10 to 150 in just three months, then wayfair.com got a bullish rating. Same story. I knew someone here in Connecticut who was the CFO of Wayfair and I said to him, “Michael, what’s going on?” And he said, “Well, I obviously can’t talk about specific numbers, but our business is booming.” So, there are two examples of stocks. And, by the way, they both come way down from their highs, even though Overstock got into crypto. They just got way ahead of themselves from a price point of view, way ahead of the valuations and the revenue and the earnings, which in the case of some of these stocks just doesn’t exist. That’s where the power gauge came in because, at some point, power gauge and the technicals turn bearish, but those are just two really good examples. There are many, many more.

Meb: Well, it’s nice because your wife is like the Peter Lynch methodology of buying products that you know, combined with the quantitative power gauge side, gives you the insight that it’s a green light or a checkbox that it’s okay. As you look at, like, sort of the market today, and listeners, you can go to chaikinanalytics.com. We’ll add the link in the show notes. There’s a lot of tools that you can kind of play around with and run some really fun names through it, type in Apple or Amazon or any famous stocks, GameStop, and see what they come up with, what sort of the market telling us today? Are there areas that you think are particularly interesting that the power gauge is flashing the green light for? There are areas that it’s saying, “Investor, be warned.”

Marc: At the risk of sounding like captain obvious, energy is just crushing it right now. And I think with good reason, not just because of inflation, because of supply chain disruptions. Metals and mining stocks come up as very bullish. And I’m using this top-down approach that we described earlier. I actually like to get more granular than sectors because so many of the sector ETFs and the SPY are homogeneous. They mix a lot of different types of stocks together, like consumer discretionary, which has everything from automobiles to home builders to retail. I like to look on the industry group level.

Meb: Well, it’s interesting because I think this illustrates a pretty important point. Investors love to get enamored with certain sectors and industries and run for the hills from others. And there’s probably no greater example of that in the past couple years, but also the past 15 years than the energy and material space, where energy as a sector got to, like, low single digits percentage S&P, and in years past during your career, it was up north of 20%, 30% of the S&P and just goes to show, you know, something got universally hated but then something starts to change and you start seeing a lot of the indicators go from red to yellow to green. Many investors would never return to those areas because they got burned by them but you kind of have to have the flexibility and be agnostic as to the industry and sector. Otherwise, to me, it seems like you’re just going to end up missing out on a ton of opportunity.

Marc: Yeah, sort of depending on an area where I’m very concerned about markets in general. It’s this whole ESG wave that’s being spurred by Larry Fink at BlackRock. But in the last nine months to outperform the market, you had to have energy stocks in your portfolio. So, I agree with you that you can’t miss out on these. Even if you are a devoted keeper of the environment and believe in ESG investing and climate change, you’re not going to make money if you’re religious about your investment choices. That’s why I created the power gauge rating. I call it an eclectic model. It’s agnostic. It doesn’t have a political point of view or care about value or growth. It just looks at the whole universe of stocks and tells you which stocks have the best potential. In a similar way, if you’re an investor and you say, “Well, I don’t buy sin stocks. I don’t buy tobacco or casino stocks, and I don’t buy energy,” I respect that. But when a wave like energy washes over the market and you’re not there, you’re going to underperform sometimes really badly. You may be doing a ton of good for the world, but what are you doing for your own retirement? You’re hurting it.

Meb: How do you think about broad market moves? You’ve obviously experienced a bear market or too and a lot of young investors today haven’t, really. I mean, we had the sort of pandemic jiggle, which was technically bear market but was so fast I feel like no one even was able to do anything. Do you think we’re vulnerable today? Do you rely on any indicators to kind of guide that? Does the power gauge, in any way, reflect that broad market sort of composition and strength?

Marc: The power gauge very definitely does, even though only 15% of the factors in the power gauge are technical. We have what we call a technical overlay. It helps us know if a stock with a very attractive 20-factor rating, meaning it has positive underlying fundamentals, is in a downtrend. New investors should look at broad market trends to have a diversified portfolio. And to me, a diversified portfolio means having some ETFs in the broad-based industries or more theme-based ETFs based on yield or industry groups, then also have some individual stocks which can add juice to your portfolio. I called it supercharging your returns. And for me, those are strong stocks in strong industry groups. So, I think your core holdings, the ones you want to stay with through a bear market because I don’t believe it’s good to be all in or all out because if you miss the top 10 days of a given year or a decade because you’re out of the market, that does more damage to your overall returns than if you miss and sidestep the 10 worst days.

But in terms of individual stocks, what I do is let the technicals deter my exposure. So, if I’m long in Nvidia and the technicals start breaking out, I’ll get out. I have a discipline. That’s what’s happened since November where a lot of our favorite stocks like Alphabet and Nvidia broke down with the market, and so I let the market take me out of that. By that I mean they either break my stops or the technicals break down, Chaikin money flow is negative. For me, it’s a way to go to cash with that portion of my portfolio, and I think that’s better than the all-or-nothing approach. Sure I have technical indicators that I look at. So, recently, we got extremely oversold, even though the S&P was only down 13% from its January 2nd high. The NASDAQ, small-cap indices like the IWM, EV stocks, they were in their own bear market. There were these crashes, mini crashes just pouring over the stock market. For instance, over 50% of the stocks in the NASDAQ composite were down more than 20% for the year.

Meb: Marc, as you look around, you know, you’ve done a lot in your career. Do you have some investment beliefs that you think you hold pretty near and dear close to your heart that you think majority of the investment populace really doesn’t? Or said differently, is there anything that you think most investors should consider that they really don’t? And this could be not just retail but also a lot of the big institutions. Anything come to mind?

Marc: Well, I think industry group strength is the key to making money on a consistent basis. And that’s why one of the factors in our expert opinion category is industry group relative strength. I think it’s completely underappreciated. Fifty percent of a stock’s performance can be traced back to its industry group. Now, would I want to own the worst stock in a strong industry group? No, but it’s probably still better than owning the strongest stock in a poor industry group. By the way, that notion is not something I invented. I think it was William O’Neil at “Investor’s Business Daily” who said that. So, I think industry group relative strength is something you just have to know about. And there are a lot of ways to get that information. My old friend, Marty Zweig summarized it best, watch the fed and listen to the market. A lot of people pay lip service to that, but really the market will tell you everything you need to know about where to put your money. Occasionally, you’ll get blindsided by something like a COVID pandemic. But, of course, that was one of the shortest bear markets in history down 33% in 23 days. But if you follow those core principles, finding the strongest stocks in the strongest industry groups, listening to the market and watching what the fed is doing, you’ll be on the right side of the market, even now with the fed being very transparent. They’re really telegraphing their moves.

Let’s look at what’s happened recently but also have a historical perspective because the reality is in a typical economic cycle, stocks go up when the fed starts raising rates. And the reason is they raise rates because the economy is getting overheated and they want to cap inflation and keep things under control. This cycle is slightly different because some of the inflation we’re seeing is from supply chain disruptions related to COVID. But I think maybe the one guiding principle, and I’ll go back to one of my original mentors, a fellow named Stan Berg at a firm called Tucker Anthony, who was one of the first quants on Wall Street back in the 1960s. He’s one of the first guys who combined technical analysis with economic, monetary, and fundamental analysis. He used to say, “People are saying it may be different this time, but, Marc, it never is. And the reason is that human emotions drive the market. Once you look beyond earnings, which are the true driver of the stock market prices, it’s human emotions that create the day to day and month to month swings that we call bull markets, bear markets, corrections, or pullbacks.” And human nature hasn’t changed since the markets became institutionalized in the 19th century.

Meb: Well said. As you look back on your career, probably made thousands of trades, tens of thousands at this point, any particular investments stand out in your mind, good, bad in between as particularly memorable?

Marc: Yeah. It goes back to something a technician named Justin Mamis said. He wrote a book called “How to Sell.” He was a market strategist with Oppenheimer & Co. And in his book called “How to Sell,” he said, “Never short a stock that’s making a new high because there’s no place to put your stop.” So, ignoring that advice completely in 1968, I shorted a stock called Four Seasons Nursing Homes. I’ll never forget. The symbol was SFM. And I shorted the stock at $99. Probably too much of it how younger I was at the time. Basically, it was a chain of nursing homes out of Oklahoma and it was wildly overpriced. I ended up covering 1,000 shares short at 19 and 7/8. It was one tick away from it’s all-time high but I couldn’t just stand the pain any longer. And that was the all-time high for the stock, and within a year, it filed for bankruptcy. So, for me shorting a stock at a new high was a prescription for disaster, and to this day I recommend that people do not try and guess tops and short stocks making new high. It just doesn’t work. There’s always an opportunity to short a stock after it’s broken down technically.

Meb: Yeah. We talk a lot about that over the years. Wrote a new paper recently that I don’t think anyone read, but I was talking about all-time highs in markets, in general, people love to try to pick tops and, in general, all-time highs are bullish rather than the opposite. Shorting is so tough, anyway. I love all my short friends. They all have a screw loose in their head. I have and continue to short. It’s a slight addiction but try to keep the position sizing small because it’s a tough game, for sure. Look, man, this has been a blast. If people want to find more about your work, if they want to check out the power gauge and run their stocks through your ratings, what’s the best place to go? What’s the best place to find out more about you and what you’re doing?

Marc: People can go to chaikinanalytics.com and see what the power gauge is all about, what our various products are.

Meb: Awesome, man. Well, Marc, you’re a legend. This has been a blast. We could go on for hours. Thanks so much for joining us today.

Marc: It’s my pleasure. Let’s do it again.

Meb: Podcast listeners, we’ll post show notes to today’s conversation at mebfaber.com/podcast. If you love the show, if you hate it, shoot us feedback at themebfabershow.com. We love to read the reviews. Please review us on iTunes and subscribe to the show anywhere good podcasts are found. Thanks for listening, friends, and good investing.