Episode #27: Porter Stansberry, Stansberry Research, “There’s Going to Be a Big Bill of Bad Debt to Pay”

Guest: Porter Stansberry founded Stansberry Research in 1999 with the firm’s flagship newsletter, Stansberry’s Investment Advisory. He is also the host of Stansberry Radio, a weekly broadcast that has quickly become one of the most popular online financial radio shows.

Date: 10/25/16 | Run-Time: 54:42

Summary: Episode 27 starts with a quick note from Meb. It’s a week of freebies! Why? Meb is celebrating his 10th “blogiversary.” (He’s officially been writing about finance now for a decade.) Be sure to hear what he’s giving away for free. Namely, his last four Ebooks are free on Amazon and he is giving away a free month trial to The Idea Farm. Lastly, our Cambria crowd round is almost full. If you’re interested you can view the raise here.

But soon the interview starts, with Meb asking Porter to give some background on himself and his company, as Porter’s story is somewhat different than that of many guests. Porter tells us about being brought into the world of finance by his close friend and fund manager, Steve Sjuggerud.

This conversations bleeds into Porter’s thoughts on how a person should spend his 20s, 30s, and 40s as it relates to income and wealth creation. But it’s not long before the guys dive into the investment markets today, and you won’t want to miss Porter’s take. In essence, if you’re a corporate bond investor, watch out. Porter believes this particular credit cycle is going to be worse than anything we’ve ever seen. Why? There’s plenty of blame to go around, but most significantly, the Fed did not allow the market to clear in 2009 and 2010, and it means this time is going to be very, very bad. Porter gives us the details, but it all points toward one takeaway: “There’s going to be a big bill of bad debt to pay.”

Meb then asks what the investing implications are for the average investor. This leads to Porter’s concept of “The Big Trade.” In a nutshell, Porter has identified 30 corporate offenders, “The Dirty 30.” Between them, they owe $300 billion in debt. His plan is to monitor these companies on a weekly basis, while keeping an eye out for liquid, long-dated puts on them that he’ll buy opportunistically. He’ll target default-level strike prices, and expect 10x returns – on average. Meb likes the idea, as the strategy would serve as a hedge to a traditional portfolio.

Next, the guys get into asset allocation. Porter’s current strategy is “allocate to value,” but for him that means holding a great deal of cash. Meb doesn’t mind, as wealth preservation is always the most important rule. This leads the guys into bearish territory, with Porter believing we’ll see a recession within the next 12 months.

This transitions into how to protect a portfolio; in this case, the guys discuss using a stop-loss service. Porter finds it invaluable, as most people grossly underestimate the risk they’re taking with their investments, as well as their capacity to handle that risk. He sums up his general stance by saying if you don’t have a risk management discipline you will not be successful.

Next, the guys get into the biggest investing mistakes Porter has seen his subscribers make over the years. There’s a great deal of poor risk mitigation. He says 95% of his own subscribers will not hedge their portfolio. Meb thinks it’s a problem of framing. People buy home insurance and car insurance. If we framed hedging as “portfolio insurance” it would probably work, but people don’t think that way. He sums up by saying, “To be a good investor, you need to be good at losing.” Porter agrees, pointing out how Buffet has seen 50% drawdowns twice in the last 15 years. If there’s a takeaway from this podcast, it’s “learn how to hedge.” There’s far more, including what Porter believes is the secret to his success. What it is? Find out in Episode 27.

Sponsors: Founders Card and Lyft

Comments or suggestions? Email us Feedback@TheMebFaberShow.com

Links from the Episode:

- The Porter Allocation

- 10% in hedges like puts on The Dirty Thirty

- 10% Gold and gold stocks

- 30%+ cash

- 25% High Quality Stocks

- 25% High Quality Corporate Bonds

- *Owns no stocks himself

- Investing to Avoid the Consequences of Being Wrong

- US Industrial Production Index

- S&P Earnings Declines

- TradeStops.com

- More information on Porter’s “Big Trade”

- Stansberry Research

Selected charts:

Running Segment: “Things I find beautiful, useful or downright magical”:

Porter:

- Save $50,000 in cash before you invest

Meb:

- Life is not a dress rehearsal

Transcript of Episode 27:

Welcome Message: Welcome to the Meb Faber Show where the focus is on helping you grow and preserve your wealth. Join us as we discuss the craft of investing, and uncover new and profitable ideas, all to help you grow wealthier and wiser. Better investing starts here.

Disclaimer: Meb Faber is the co-founder and chief investment officer at Cambria Investment Management. Due to industry regulations, he will not discuss any of Cambria’s funds on this podcast. All opinions expressed by podcast participants are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of Cambria Investment Management or its affiliates. For more information, visit cambriainvestments.com.

Sponsor: Today’s podcast is sponsored by FoundersCard. I usually don’t spring for paid membership programs, but this one is a little different. The offering is targeted at entrepreneurs and business owners, and the card enables premier benefits from leading airlines, hotels, lifestyle brands, and business services. A few of my favorite benefits include free access to MailChimp Pro, Dashlane Premium, and TripIt Pro. You can even get big discounts of services I love like Silvercar, 99designs, Apple, and AT&T. My favorite though, are the travel benefits where you get an automatic status such as Hilton Hhonors Gold, American Airlines Platinum, and Virgin America Gold. And while I often use the great app, HotelTonight for travel, the FoundersCard discounts can be massive, too. If you go to founderscard.com/meb, podcast listeners can sign up for the discount at 395 bucks a year with no initiation fee, and that’s a saving from the normal cost of around 600 bucks per year. Again, that’s founderscard.com/meb.

Meb: We have a great podcast coming up for you today with special guest Porter Stansberry. But before we get started, wanted to let you know that today marks the 10-year anniversary of my very first investment blog post. In honor of this 10-year blogiversary, as we call it, I’m gonna give you, the listeners, 5 gifts [SP] and also ask for something in return. But first let’s take a look back. In the last 10 years, I’ve written over 1,700 articles on the blog. That equates to about 15 per month. We’ve written 10 white papers, 1 of which is the all-time, number 1 most downloaded on the SSRN database, with over almost 200,000 downloads, and that’s out of a half of a million papers. We’ll also update that when it has its 10-year anniversary this February. We’ve had readers in over 200 countries around the world, and we’ve also written 5 books. So to celebrate, all week is gonna be a week of free giveaways.

First, I’m making all of my e-books free to download on Amazon all week. Monday to Friday, you can download the last four investment books I’ve written, my gift to you, all week long, no strings attached. Second gift to you, I’m gonna offer every single listener of this program and the blog a free month of our investment research portal, The Idea Farm. If you go to the blog post, and we’ll link to it on the show notes, for my 10-year blogiversary, we’ll have a link to let you sign up for a free month, The Idea Farm. Again, no commitments, no strings attached, cancel at any time. Enjoy.

Lastly, the one thing I want to ask for you, as you’re likely aware, my company Cambria, just launched our new investment management service called the Cambria Digital Advisor. We’re really proud of this service, spent a many years building it, and I honestly believe it’s the best way I know how to put together a portfolio that has a lot of tilt such as value, and momentum, and trend. And I believe in it so much, it’s how I invest 100% of my net worth. So if you could do me a favor, take a minute, visit cambriainvestments.com, check out our new digital offering.

And lastly, I wanted to say thanks to all the podcast listeners and blog readers that have been around for 10 years. You all made it what’s possible. I often get asked, “Meb, you know, how do you churn out so much content? Do you not have a life? What’s the deal?” And I say, “No, actually, like, the biggest benefit is 10X benefits me getting to meet the people, the wonderful, idiosyncratic, intelligent, quirky, wonderful listeners that have been following for 10 years. So a big shout-out. Thanks to you, and here on to the show.

Meb: Hello, friends. Welcome to the podcast today. We have a special guest and close friend, Porter Stansberry. Welcome to the show.

Porter: Hi, Meb. Great to be with you.

Meb: Porter, where in the world are you Skyping in from now?

Porter: Well, today I’m actually home. I’m on my corn and soybean farm in Baltimore County, Maryland.

Meb: I didn’t know you were a fellow farmer. What is the… How are you getting by on these low crop prices? Corn seems to be at a generational lows these days. Is that a profitable venture for you, at all?

Porter: Meb, as I think you know, I’ve done pretty well on finance side of things. I don’t wanna leave my kids with the burden of wealth, so I’m gonna farm it till it’s gone.

Meb: Great concept. We just had a combine catch fire, you know, when we were talking about black swans and everything else in the investing world. A combine catched fire, burned down a bumper wheat crop that we had in Kansas. But thank God for insurance, covered it recently. Look, before we get started on the investment side, which I’m sure people are super interested in, figure we talk a little bit about your background. You know, a lot of people obviously are familiar with you, but some of our audience may not be. And I kinda came to you through a common friend, who we’ll have on the show pretty soon, he’s one of my favorite investors, one of the…my number one reads, Steve Sjuggerud, who by the way, seems to be recovering from walking pneumonia. But I met Porter through Steve. So Porter, why don’t you give us a little background, how you got started in the investment research business, and a little bit about how you’ve kinda grown Stansberry over the years?

Porter: You know, Meb, it’s a pretty simple story. I knew a really brilliant guy growing up, Steve Sjuggerud. Steve was our community’s Doogie Howser. If you’re of a certain age, you’ll remember the TV show about the super young kid who goes on and becomes a doctor by the time he’s age 16. So Steve was managing a big international mutual fund by the time he was 23. Meanwhile, I’d just grown up serving [SP] with him ever since I was 12 years old. So he was a whiz kid at finance, and I was a guy who really liked to read and think, and I was a history major at University of Florida with a little science major thrown in there, too. And when I got done with college, I didn’t really…I was at loose ends, I didn’t really know what I wanted to do next. And Steve said, “Hey, I’ve got to go to China for two weeks to research this new Pudong area,” which as you know now, has just exploded. This is back in 1996, so that’s how far back we go. And he goes, “Why don’t you come and spend two weeks at my office, and if you like the work, I’m sure we can find a place for you?” So that’s what happened. I graduated from college and I drove down to…we had a little office in Delray Beach at the time. And I started working for Steve. And one thing just led to another. And I think that we, Steve and I, have been more successful than most in this business because we came at it with the attitude that at the time, a lot of the publishers didn’t have. And it sounds a little simple, but I’m telling you back then the investment newsletter community was dominated by people who were using newsletters to promote penny stocks. And Steve and I thought, “This is a great business. Why don’t they just give some good advice and then they wouldn’t have to go out and get new customers every year?”

And so we sort of built our business, step by step, by trying to do what we would want our newsletter to do for us if our roles were reversed. So since day one, we’ve been trying to give the very best of Wall Street’s analytics, and thinking, and contrarian strategies to investors at a very fair price. And I think that’s something that resonates with you because of course on your side, you’ve been using a new structure, the ETF, to lower fees and deliver great value to people, and that’s been your key for success. And ours is the same, “Hey, let’s hire really talented, smart people. Let’s research areas of the market where people can get great performance, and let’s charge a very reasonable price for our work.” What do you know, 20 years later, we’re an overnight success. Today we employ over 400 people, we have almost a million subscribers around the world, and we have 8 major franchises that we own and manage. And we’re always looking for more. So if you own a good research business and you’re interested in selling or partnering, don’t hesitate to reach out.

Meb: You know, and it’s funny because when I first met Steve, and I didn’t know Steve from anyone, and we had dinner with a common friend, Van, who also get on the podcast at some point. I remember Steve had written about my first book many years ago, and had sent me an email and said, “Hey, Meb, just wanted to reach out, enjoyed your book. I’m gonna write about it in my newsletter the next day.” Sure enough, next day, I wake up and I said, “I don’t know who this guy is.” Book sells out on Amazon, which is really, really hard to do, by the way. And so I said, “It couldn’t have been that crazy newsletter writer,” and I had had a bias at that time, you know, about the newsletter side of the business. Like you mentioned, there’s a lot of sort of snake oil out there, a lotta these penny stocks sorta newsletters, and have come to known Stansberry, we just got back from y’all’s conference, and probably nowhere else in the world can you sit down and be seated at a dinner table and to your right is a guy that had climbed Everest and skied down, to the left is a hypnotist and then…and a boat captain, and then three other famous hedge fund managers.

So I’ll give you a compliment before, you know, we start debating and then I’d hold your feet to the fire a little more, and that’s that, you know, in a world of sell-side research, Stansberry, I will give the compliment of it being plenty of free thinkers. You know, you end up with a lot more interesting perspectives. And so one of the comments that will probably start to segue from the business side into sort of the investment side, Steve had attributed a quote to you that said something along the lines of, “Your 20s are for learning, your 30s are for earning, and your 40s are for owning.” And I may have gotten that wrong, but maybe you can talk a little bit about that, especially with regards to kinda your experience in your business career, and also how that kinda segues a little bit into the investing world.

Porter: Yeah, you know, Meb, when you’re successful in business, people want to ascribe to you all sorts of wisdom. The truth of the matter is we built this business just by putting one foot in front of the other. We didn’t do anything fancy. There was no magic. We just showed up for work every day, we spent 10 to 12 hours at the office, and we tried to come up with work that we would want to buy. And really it’s that simple. We had a refund policy that was very generous, we had great customer service, and we have good products. I would put our research up against any investment bank in the world, any hedge fund in the world. Take a look at our insurance stuff, for example. There’s nowhere on Wall Street you can get insurance information like the kind we provide, where we give you the entire industries, their float, and we give you a way to value them. And that stuff is very hard and complex to calculate. You can’t just use Bloomberg to do it.

So those are the kinda things that we do that set us apart. Because of that, we’ve been, you know, I think extremely successful. I don’t think there’s any other, outside of “Wall Street Journal”, “New York Times”, I don’t think that there’s a financial publication organization in the world that has a million paying subscribers. In addition to that, we have about two million free readers on a daily basis, which makes us quite a bit larger in total readership than “The Wall Street Journal”. And it’s fun because most people never heard of us, so they don’t see us coming. You know, a lot of our competitors, as you mentioned, have lower quality research and have a business model that’s not quite so one-sided as ours. They’re trying to play both sides, they do a little bit of investment banking, they do a little bit of newsletters. By focusing just on the research, we really have an offering that’s unique. Because of that, everyone wants to know, “How did you do it?” You know, and so they ask me all these questions about career development, things like this. And the only thing I can tell you is, whatever you spend your 20s doing, that’s what you’re gonna end up doing for the rest of your life, unless there’s something very extraordinary that happens to you along the way. It doesn’t matter what you get paid in your 20s, as long as you’re learning something that you know will be valuable for your life.

Just imagine if you spent your 20s working in, you know, kiosk retail. You know, you had…you put in your 12 years at Radio Shack. What do you really know how to do? And is there gonna be demand for that going forward? Or let’s say you spent, you know, your first 10 years outta college working at a newspaper. Those are bad decisions, and I would tell you you’ll be way better off, even if you took a reduction in pay, by going into a field where there is plenty of growth potential. You know, I don’t care if you just sweeping the floor at Engen. Biotech is going to be an industry that grows for the next 50 years, and you’ve got to get in on it somehow.

So, in your 20s, when you don’t have to have a lotta money, do that. Do whatever it takes to get a job where you can learn to be a part of an industry that’s gonna be successful. For me, that was finance. And my first job was the research assistant for Steve Sjuggerud, and my first salary was $20,000 a year, and I lived on a futon in Steve’s living room. That’s what happened. That’s not a myth, that’s reality. And I think a lotta people, especially millennials, they have this attitude that they don’t have to work very hard, they can have work life balance, all these buzzwords. And maybe you can. If you can, well, you know, you figured it out and I didn’t. But I think what you should do in your 20s is do whatever it takes to get an education in something that’s very valuable, and to network and build connections. And if you do that and you do it well, by the time you’re in your 30s, your work should be recognized as being very good. And at that point, that’s when you can demand higher salaries, and you can demand bonuses, and you can play the corporate game where you switch from one company to another to get more money. And if you do that, and if you’re successful with that, you keep working hard, by the time you get into your 40s, you should definitely have an ownership stake in what you’re involved in, and you should look to acquire more. At Stansberry Research, I don’t think we did any acquisitions at all until I was in my late 30s. And we’ve been doing about one a year since, and it’s made a huge difference in our business. And I tell you, you don’t know enough to be an owner until you’ve spent 20 years doing something, because you don’t know what you don’t know until that point.

Meb: Great advice. You know, although I will say that if I had ended up doing what I was doing in my 20s, I would still be a ski bum today. But I was at least going to the same theme. I was ski bum but also working for very low pay for a commodity trading advisor, that since went bust, but I did learn a lot in the spare time. But I agree, we have a lotta people that say, “Meb, give me some career advise,” etc. etc., and, you know, it’s always, you know, “How do I find a job at XYZ?” And from the opposite side is, “Demonstrate some value.” You know, say…if you say, “Hey, I’m gonna work for free or very low cost, but also let me show you how I can add value from day one,” most people that come to our door, send me an email say, “Hey Meb, How do I get a job?” You know, and they’re essentially asking me for something. And most people seem to get that wrong, when really they should be saying, “Look, what can I do to, you know, demonstrate value in…with the realization that I’m young and I will learn and probably get more outta this equation than you will?”

One of the cool things that you guys do that I don’t know that too many companies do in general, is that Stansberry has this spring editor’s conference where they have, you know, an off-site for their company, but they’ll invite in a handful of outside of the company thought leaders, or investors, or researchers, but a very diverse set. And I’ve been to a couple of these over the years, and have been very impressed that y’all kinda open the kimono at these sorta meetings and say, “You know what,” kinda meritocracy style, “anyone has suggestions, anyone has inputs, you know, feel free to suggest, or let’s creatively destruct some of the ideas here.” You wanna talk about that for a second? And how did you come up with that idea? Is that something you guys just one day said, “Let’s go do a fun spring trip?” Or was it something that, you know, you had thought about and grew over time?

Porter: Well, it’s a little bit of both. I’ll tell you that at the heart of our corporate DNA, and at the heart of every great investment analyst, is an unquenchable curiosity and thirst for knowledge. It’s amazing that there…you know, there’s so much information that’s available on the Internet, and that’s great. And of course we use that tool, and we read all the SEC reports, and we read the press reports. But there’s no way you’re gonna really understand how another business works until you have spoken to someone who’s done it for 20 years. And then it’s amazing how quickly you can come up to speed with how an industry works if you’re able to talk to somebody who spent their lifetime doing it.

At the core, our spring editors meeting is about getting our analysts exposure to people who’ve really done it. And a great example of that is, we had Andrew Fastow, the former CFO of Enron at our last spring editor’s conference. And a lotta people were very upset with me about this, a couple people threatened to resign. And I said, “No, you don’t understand. I’m not a fan of Andrew Fastow, I think he’s a complete sociopath. But if you want to know the pitfalls of accounting, that’s the guy to talk to.” And sure enough, we spent a couple days with Andy, and he is a sort of a sociopath, sorry, Andy, but we learned a lot about the different ways that people can still gain the accounting that most investors use. And that was very helpful and eye-opening for a lotta my staff, especially the younger folks. So that’s the real point of it, just trying to let people learn from face to face interactions and not doing everything over the phone or over the Internet.

And then the second thing is, it’s been very tough for us over many years to break through that reputational barrier that we faced. You spoke to it, newsletter guy, “Why am I gonna return his call?” Well most people just don’t know how many smart folks work for us, and they don’t know the reach of our products and our list. But when they come to this meeting, their idea of us can be transformed immediately. So they meet us, they work with us, they sit down and have a meal with us, they exchange ideas, and that’s very helpful as a first step towards buying a business or partnering with another guy.

Meb: Let’s start to move over towards a little of the investment side. You know, I read quite a few of y’all’s publications. There’s some interesting takes on the world that y’all have, particularly right now, and you, in particular, Porter. Maybe you wanna talk a little bit about some of the dangers or opportunities you’re seeing in the markets right now, and any thoughts in particular about the way the world looks right now in 2016?

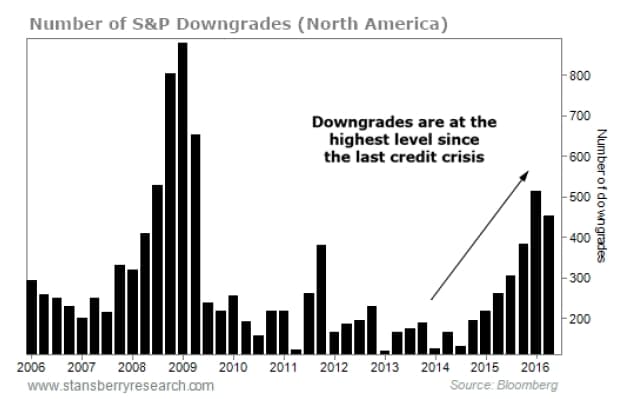

Porter: Yeah, I think that there’s a dramatic opportunity to see a period of discontinuum, if you know what that means, in 2018, 2019, where the models won’t work, where the historical references fail, where the underlying foundation of the market is really challenged, and you have what people would call black swan events or just huge volatility. And we’re approaching that period of discontinuum because of the credit cycle. And this particular credit cycle is gonna be far worse than any that we’ve ever experienced because the underwriting was sloppy, the amount of debts that were underwritten are enormous, record setting, and most importantly because the Fed did not allow the market to clear in 2009 and 2010. So there’s just a huge number of zombie companies out there, folks that have been given credit, particularly corporate credit in the bond market, that simply don’t deserve it. So there’s gonna be a big bill of bad debt to pay. And I don’t think it matters, by the way, whether or not the Fed raises rates or doesn’t raise rates.

Meb: And so what…where do you kinda see the investment implications? Is this the sorta situation where you say, “Okay, look at the credit worthiness of some of these companies,” and step back, or are you avoiding stocks, or are you actually going long or short particular sectors or companies? What’s one to do with kinda this information?

Porter: Well, it’s a very interesting situation because the Fed has put out so much liquidity. And it’s ended up in two places, and I’m sure you know this. But isn’t it interesting that both junk bond issuance and stock market volatility are both at record levels? Meaning volatility’s at record lows, and junk bond issuance is at record highs.

Meb: So Porter, tell me about your thesis here. I know you’ve written about it and you’ve called this “The Big Trade”. What’s the implications here?

Porter: You know, when you see a market that’s this far out of equilibrium, you know the volatility on stock shouldn’t be this low, and you know that interest rates on junk bonds shouldn’t be that low either. And you know that both are a factor of the Fed’s interest rate policies that simply can’t last forever. Kinda like what a group of speculators did during the mortgage bubble, you want to position yourself in a very asymmetrical way to make a lotta money if corporate default rates end up being higher than people expect over the next two or three years. And you do that by buying outta the money, long-dated put options. And you can finance that in a variety of different ways. You can use junk bond coupons to finance that, or you can do various kinds of options trading to finance it, so that if your timing is off, you’re not gonna lose 100% of your investment if the put expire’s worthless [SP].

And the timing certainly is important. Right now the default rate is just over 5% for U.S. junk bonds. I expect that’ll be in the double digits by the end of 2017, and I expect it’ll be above 15% for all of 2018. And that’s really what we’re trying to set up. We’re trying to get our position set up during the next 12 months so that we can have huge wins in 2018 and 2019 when the default rates really skyrocket.

Meb: And so and how do you…are you kind of applying that? Is that something where you’re targeting specific stocks or ETFs and you’re buying the puts? And if so, are they, you know, are these, like, 12-month puts, and then are you kinda reevaluating once a quarter? Like you said, the timing’s hard. So is that something… What’s the general portfolio management approach to that?

Porter: Well what we did, first of all, was we went out and we said, “Look, we don’t want to try to trade puts on everything. We want a very select group of stocks.” And there’s, you know, there’s 30 stocks in the Dow Jones Industrial Average. So we said, “Let’s find the worst 30 stocks in the market that have a large amount of equity value left.” So we found what we call the “dirty 30”. And these companies collectively owe $300 billion in debt. And they still have about $250 billion in market cap. So these are big companies that are liquid, where we can get options at very, very low prices. And they also have fixed income that trades around this, and so there’s all kinds of different setups. But what we do is we monitor these stocks on a weekly basis, and we look and see what’s the most liquid long-dated put? What’s it trading for? And we’re looking to buy opportunistically. So when the put price falls 20% or 30% a week, which isn’t unusual, then we look to buy that one, and we look to structure a trade to minimize our downside if, you know, the company doesn’t default before the put expires.

Right now we’re looking primarily to buy January 2019 puts, and we’re looking for strike prices that indicate a default. So we’re looking at strike prices below five dollars. So these are very, very low-cost options. And of course by getting the cost down, you really can jack up your potential returns. Our target is on average is to make 10X on each of these positions on average. And to do that, you’re gonna have to make 20X and 30X to make up for the places where you have losses.

Meb: It’s interesting, you know, the nice thing about this concept to me, too, is it ends up being a potential hedge to what most people have in their portfolio. You know, we see people come in every day with portfolios, it’s almost always just U.S. stocks and bonds. And our thesis right now of course is that U.S. stocks are on the expensive side. And historically, U.S. bonds have been a great hedge to a stock portfolio when times have gone south for stocks, not always, but usually. And the big challenge of course now is with U.S. bonds yielding one and a half percent, 1.7%, is, you know, how much juice is there to be able to hedge the U.S. stock market when it does poorly? And so we often talk a lot about other asset classes. Certainly, you know, Steve and I have a very similar philosophy with trend following, but one of the problems with bonds hedging is it may not happen this time. And so something like this, to me, is an interesting potential hedge to the rest of the portfolio because, you know, if these corporates go south, there’s no chance that the broad equity market probably continues its raging bull. We did a stat the other day on the blog that said we are now in the third longest Dow bull market ever. If we make it through the election to December, it’s the second longest, and if we make it ’till spring time, it is the longest bull market ever. It’s not the biggest by magnitude, but longest certainly.

So how do you think about…either if it’s your own money or you’re talking to investors, how do you think about asset allocation? You know, I saw a note that you had in one of your articles over the past few weeks, where an investor said, “Hey, look, can you tell me how to allocate your money?” And of course, you said, “Look, we can give you advice, but here’s what I consider to be a reasonable kind of allocation.” Maybe you can talk about that for a second. I don’t know if you remember the exact numbers or response, but maybe how you think about asset allocation and what, for a particular investor right now, what would be sort of a reasonable allocation for their portfolio?

Porter: Yeah, I have an interesting idea about allocation that I have developed over a long period of time, and I just call it “allocating to value”. I don’t think that you could necessarily time the market on a daily, weekly, monthly, yearly basis even. But you could really fade, you know, ridiculous valuations, and you could really…you could lever into things that are very cheap. So if you look around the world right now, I would tell you the most overvalued asset in the world is corporate junk bonds. You know, just look at the math. These things historically, of the bonds that have been issued over the years, something like 30% to 40% of them eventually default, yet they were yielding less than 5% at the peak in May of 2015. And, well, that’s not even gonna cover the cumulative default risk. It’s not gonna cover it. You’re locking in losses when you buy junk bonds at that level. And by the way, things got worse in a lotta places. In Europe, they had corporate junk bonds that had negative yield to maturities. That’s where investors who don’t want to wait a couple years to lose all their money, they wanna lose it right now.

When you see these kinds of things, these phantasms, these absurdities, you know the market’s not perfectly efficient or they wouldn’t exist. But you also know the market’s reasonably efficient, so they’re not gonna exist long. And you wanna set up your portfolio to profit as these trends revert to the mean. Right now, I wanna buy what’s cheap, which is put options on really poorly finance companies. And you can buy ’em for nothing. And a year or two, that stuff’s all gonna be trading for three or four times more, even if there hasn’t been a default, because the volatility’s gonna go up and the interest rates are gonna go up for those particular companies. There’s no question. Likewise, like you said, I think stocks are on the expensive side, so you’d want to fade that. My advice was, you know, basically something like 10% in gold as a hedge, and gold means bullion and gold stocks combined. Something like 10% in hedges, so that might be short stocks or long puts from the big trade. Something like 40% in cash, because you’re gonna wanna have a lotta dry powder when this thing ticks over. And then something like 25% in high quality corporate stocks, and 25% high quality corporate bonds because you don’t wanna make no money if it takes longer than you think.

And I think that, you know, obviously those things all sum to more than 100, so you’ve gotta kinda go back and work what’s right for you, and what you’re trying to achieve with your investing, and what your risk tolerances are. As for my own allocation, I’m happy to tell you I don’t own any stocks right now, zero. I have some money in private equity deals, I have some money with [inaudible 00:28:43] at Stansberry Asset Management, and I know he owns stocks with some of that. Personally, in my own personally direct accounts, I don’t own any stocks at all. I’m really interested in buying more bullion, that’s the only thing that I really feel great about right now. Over time, as we develop our work into this big trade idea, I plan on allocating heavily to those trades. I think that there are…I think that’s my best chance at becoming a very, very wealthy person in the next five years.

Meb: You know, it’s interesting, there’s two comments I wanted to make, one is that one of our guests on the podcast, Rob Arnott, who manages, you know, many hundreds of billions, had a great description of kinda what you were talking about, where leaning towards value in away from over-expensive, where he called it “over-rebalancing”, meaning a lotta people have traditional portfolios where they say, “I have 20% in X, Y, and Z,” and they’ll rebalance the target every once in a while, which gives you a bit of that buying cheap and selling expensive as it’s coming back to your target. But the phrase you use and kinda what you’re talking about, which is over-rebalancing, meaning, A, if emerging markets are cheap, I’m not gonna just rebalance them to the 10% I normally allocate, maybe I’ll go to 15%. And if something’s expensive, I’m not gonna take it, you know, back from 20 to 15, but maybe down to 10. And so that gives you a little bit of the tail wins from, you know, valuation over time.

And second comment I wanted to make was that William Bernstein, you know, very famous doctor, physician who’s also written a lotta books on asset allocation, he had such a great point that echoes some of your sentiments, which was, you know, when people…a lotta people that have become wealthy, and, you know, whether they have enough money just to pay for their daily bills, they don’t have to worry about working again, or whatever it may be, his comment is always, he says, “Look, you’ve won the game. You have a portfolio.” And the biggest mistake he sees a lot of those people make is they take way too much risk, meaning they’ll still put 70% or 80% in stocks, and then, you know, as we’ve seen in these last two 50% bear markets in the U.S., they cause themselves so much emotional, and psychological, and monetary pain by…and distress by, you know, blowing up what they’ve built so many years to achieve.

And so your comment on cash I think is very useful to listeners because a lotta people… You know, we always say asset allocation, you know, the broad asset allocation is a lot more about wealth preservation than about wealth building. And for the wealth building, you either need to do a couple things: One, build and own a company, kinda like you mentioned earlier, but also come up with some of these asymmetrical ideas where it’s not just gonna be about whether you’re gonna earn 4% or 5%, but whether you’re gonna earn 5%, or 20%, or 30%. So that’s interesting. So, you know, one of your other comments you’ve made, and I’m curious kind of about what ends up being the trigger on some of these events, you say there’s a pretty high chance of recession in the next year or so. What is kinda driving you to that consideration? Is it this corporate bond build-up, or is it other indicators you’re looking at that would cause to push the U.S. into…economy into recession?

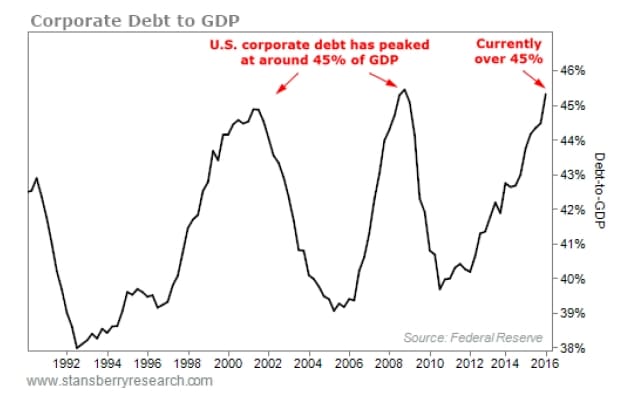

Porter: Well there’s lots of classic economic warning signs. The most notable is that U.S. industrial production has been falling since 2015. You know, there isn’t a period in U.S. history where that didn’t signal the beginning of a recession. That’s number one. Secondly, you know, we’ve seen huge, huge declines in global trade. Again, that’s another coincidental indicator with global recession. I was shocked, it was a week or two ago, China reported that their exports fell 10%, year over year. I mean, that is such a huge number, it’s hard to get my head around. And you gotta remember that quarter included the launch of the iPhone 7, all of which is manufactured and exported from China. That is a big problem for the global economy, that the demand is so weak that China’s exports would fall that much. And then I think most importantly, those things are very important indicators, but the two that really strike me as being more important to financial folks is that the S&P 500 is looking like it’s gonna hit its sixth quarter in a row of declining earnings. And with multiples being as high as they are, I just don’t think the general stock market level can sustain declining earnings for very long. And of course, also that’s an indicator of recession. You don’t normally see earnings decline for more than a year without a recession. And then finally, the most important one to me is just the credit cycle. If you look at that the default rate on junk bonds, if you look at whether or not banks are tightening or loosing lending standards, and if you look at the total amount of corporate debt that’s being maintained, those things are extremely cyclical, and there is a well-known six to eight year cycle.

And right now, U.S. corporate debts are more than 45% of GDP, which is a new all-time high, and it shows, if you look at the history, that debts will roll over at this point and you’ll have a recession. Likewise, if you look at the default rate, as I mentioned, the U.S. junk bond default rate has tripped over 5%. That’s always signaled a new default cycle and a recession. So I think that the evidence is overwhelming that we will develop a recession in the next 12 months. And I think the evidence is overwhelming that if you look at the dirty 30 companies I’ve selected to trade long-term puts on, those companies just have no future. It’s laughable how much credit has been extended to these people. Collectively, they hold $300 billion in debt. And over the last 10 years, the net collective cash flows from these businesses is negative $40 billion.

Meb: You know, you’ve made a lotta good calls over the years. I mean, I specifically remember sitting in some of these conferences where you were talking about the huge risk to oil price when it was trading back above 100. You know, and I remember listening to you say, “Hey, look, this could easily go below 50.” You know, you famously talked about Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the summer of 2008. So kudos for you on those. But like any good investment analyst, I’m sure you’ve had some calls or thesis over the years that maybe didn’t work out. Are there a few that come to mind where you had a kinda strongly held opinion, and things just didn’t really go your way, or the world changed? Any in particular come to mind?

Porter: Oh sure, that happens all the time. I think the most significant one is I was convinced that we were gonna have a real problem with inflation following the size and scope of the Fed’s bailouts in ’09 and 2010, and it really didn’t develop. And I’ve been working on understanding why that happened ever since. Think there’s a whole new revolution coming to the economics profession and understanding the impact of highly indebted economies and what trouble they can get into. So I would say that’s the most classic one. But you know what I’m happy about, Meb, is, you know, when the facts change, I work really hard to make sure I change my mind. So I went from being short treasury bonds to being long treasury bonds about 18 months ago and it’s been a fantastic trade.

Meb: And one of the things you guys talk a lot about and I know you’ve been a proponent on, and I don’t know if you’ve changed your mind over the years or not, but thinking about having positions in using sorta trailing stops, or using stops on positions as a “throw your hands up and move away”. And I know Steve does a lotta that. Is that something you incorporate into your methodology as well, or?

Porter: Absolutely, absolutely. And I would urge people, if they have never heard of or never used a system like this, to at least go to tradestops.com and see what it’s all about. And it does two things for people that I know, Meb, you will appreciate. Number one, you can put your portfolio into it. You can enter your stocks. It’ll tell you how risky, how volatile your portfolio is relative to the S&P. And the number one thing that I have encountered by working with individual investors for over 20 years, is that most people grossly underestimate both the risks they’re taking and their capacity for those risks. You could enter your information, you can find out how much risk you’re taking, and I guarantee you’ll be shocked. And the second thing that it does that’s so important is it’ll allow you to balance your portfolio for risk. And Meb, I know you have read about all this as much as anybody has, you’ve written about it, but this risk-based position sizing is such a cool idea and it allows people to dip their toe into stuff like a small gold stock or a speculative biotech without wrecking their portfolio. And it keeps your money centered on your best risk to reward opportunities. For example, my portfolio, I’ve long been a proponent of investors owning Hershey. And one of the reasons why I really like Hershey is because it has so little volatility compared to its very high returns on invested capital.

Meb: With trailing stops it’s interesting because you end up with a very similar methodology to what we think about trend following in general. And it’s a different execution of course, but one of the biggest things is you’re starting to cut off the left tail of investments. And a lot of investors don’t really realize, and there’s a lotta behavioral research that talks about this is, you know, a very simple example is an investor buys something, a stock at 100. They’re forever anchored to that number. And so let’s say it goes down to 80, and they say, “Oh, man. That idiot broker that put me in that, he’s a moron.” And then it keeps going down to 60, and they start pulling their hair out, and they say, “You know what? I’m gonna sell it when it gets back to 100.” And the next thing you know, it goes down to 40 and they say, “Well, look, there’s no point in selling it now. I’ve lost almost all my money in it. I’m just gonna hold on to it. What’s the point of selling it now?” And then of course, what happens next, we all know, it goes to zero.

And there’s a great study we mentioned a few times on the blog and the podcast from our friends at Longboard who we had early on in the podcast called The Capitalism Distribution where they talk about it’s roughly 20% of all listed stocks in the Russell 2000. So these aren’t [SP] microcaps, essentially go to zero. And roughly 40% of the total universe essentially has zero rates of return, so you have this very small minority of stocks, the Amazons, the Walmarts, the Apples of the world that end up having these just huge multibagger returns. And that’s one of the reasons a market cap-weighted index like the S&P, you know, works, is because you end up owning less and less of a stock going down and more and more of a stock that’s going up. So it’s a naive trend following strategy. So the same thing is if you hold a portfolio where there’s 20 or 30 stocks, the beauty of something like a trailing stop, and our friends run a site that kinda does this for you, TradeStops, is that, you know, they’ll quantify it. They’ll say, “You buy this stock, here’s the volatility, here’s a sample trading…trailing stop,” and it gives you the peace of mind of, “Look, you’re out. Don’t have to worry about it, there is a sell methodology.” Otherwise people in general, they get used to just riding it all the way down. And I think that applies to macro asset classes as well. You know, you guys talk a lot about real assets and assets such as gold a lot more than most people do, and I think it applies there just as easily.

Porter: Yeah, I can tell you all kinds of great stories about subscribers who did round trips on things like JDS Uniphase that at one point was up 5,000%, or something. So they had life-changing wealth and they couldn’t bring themselves to sell. It goes from 3 to 500 and back to 3. And you tell them, “We’re out,” and they just can’t…they can’t wrap their heads around the fact that you’ve sold. Lots of stories like that. And there’s no doubt that unless…if you don’t have a risk management discipline and strategy, you will not be successful.

There’s one other thing about trailing stops that I think is very important, and that is it can help you to time the market generally. And let me give you an example. In September of 2008, our resource newsletter, which recommends investments in everything from base metals to gold stocks, to oil companies, to land holdings firms, it’s a general hard asset newsletter. It stopped out of every single thing in its portfolio by September the 15th of 2008, which is right about the time that Lehman failed. And you think, “Well, how’s that good? That means that all these things were down at least 25% from their high. Some of them were down even more.” Well, go and look at the commodity indexes from mid-September through the end of November of that year. They went on to fall another 50%. So if you had sold when we sold, you would have had tons of cash at the bottom in November and December to load back up, and you would’ve been able to get in at much more advantageous prices. And so that’s just a good rule of thumb. You know, set your loss limit and stick to it. Doesn’t mean you can’t ever buy that asset again, and it does mean that you’ve limited your risk. And that’s crucial, as you said, you’re eliminating the left half of the bell distribution.

Meb: Well, we always say that, look, the biggest challenge with trend following or something like trailing stops for people is that they don’t follow the system, and so they never want to sell a lotta the assets when they signal a sell, and they never want to buy when it signals a buy. And if they’ve had multiple losing trades in a row, so if you think about a market that’s going sideways, they end up saying, “The system is broken, I no longer wanna use it.” The biggest challenge though, is of course the same thing happens with buy and hold. You know, a lot of investors struggle with buy and hold for the same reason where you have a methodology where you’re not supposed to do anything other than buy and hold. And of course, what you mentioned earlier, the large draw-downs you have with asset classes and portfolios, people will start to sell when they go down more than they expected. And in many cases like a diversified portfolio even in 2008 would’ve lost buy and hold, would’ve lost 50%.

So a lotta people struggle with buy and hold for the same reason. And so the nice thing about the trailing stops is at least for a lotta people, it gives them some mental comfort that, you know, one, that they’re doing something, and two, at least they’ll live to play another day, which we always say is the most important rule in investing, is at least survive to invest another day. You deal with millions of subscribers, individuals mostly. What are some of the most common mistakes you think a lot of investors are making and the prescription for those? I mean, I know a lot of them, we’ll have mentioned before in the past, but you’ve been doing this long enough. What do you see on a consistent basis as some of the major couple mistakes people make on a ongoing basis?

Porter: Well, just to be clear, we have just under one million paying subscribers and we have about two million free subscribers. So I don’t wanna exaggerate the size of our business because we’ll have our peers in the publishing world calling us liars before you know it. To answer your question, it’s all of the biases, Meb, that you’re extremely familiar with. I’d say the biggest mistake that individual investors make is they just do not appreciate that volatility goes both ways. So you’ll see them partying when their stock goes up 15% in a day. And it never occurs to them that if a stock can go up 15% in a day, it can definitely go down 30% in a day. They just don’t understand how to limit position sizes, they don’t understand the importance of managing volatility and risk. I would tell you that I bet you 95% of the people who read my newsletter will never do anything to hedge their portfolio. They don’t understand the idea that sometimes you wanna spend money to make an investment not because you expect it’s necessarily gonna work out, but because it will work out 100-fold if everything else in your portfolio goes to hell.

Meb: I think so much of it has to do with the way that people frame it. You know, people have no problem buying insurance for their car, or medical insurance, or home insurance. And you kinda frame it that way as, “Hey, can you buy insurance on your portfolio?” I think people would respond reasonably well to that. But, you know, something about the strategies, and the hedging, and the terms, you know, they don’t put it in the same bucket, they just expect all the investments to make money. You know, we had a funny story, there’s a local investment manager who manages in the billions and his buy and hold guy. And he has this beautiful website that has these sliders that say, “You buy portfolio X, this is what your historical drawdown’s gonna be,” etc. etc. And I had met with him, you know, right after 2008/’09 happened. I said, “Well, what were you showing people before ’08/’09?” And he said, “Well, I just readjusted the slider scale.” So I said, “Well, that’s great for someone now that, you know, had a 50% drawdown, but back in ’07, they were expecting a 20%.”

And so the, you know, listeners, there’s two quotes here. One, by definition, your largest drawdown will always be in your future, mathematically speaking. And two, most investments and markets spend most of their time in some form of a drawdown. So there’s only two phases for a market, taking the S&P 500. It’s either at an all-time high or it’s in a drawdown. Now, the drawdown may not be much, it may be 1%, it may be 5%, but to be a good investor, you need to be good at losing, because the vast majority of the time, and I think it’s around 60%, 70%, 80% for various markets, you spend not at an all-time high. So the U.S., we’re near all-time highs now, not as much for the rest of the world. Porter, we’re gonna start to wind this down. I don’t wanna keep you too long. We’ll get you back on the podcast in 2018 to see how these corporate bonds are doing, if I’m still podcasting by then. But we start to always ask guests on the podcast, back one of our original posts is something most people may or may not know about, the beautiful use for magical. You have anything for us today?

Porter: Just talking about drawdowns and losses. If you think about the fact that Warren Buffett, who’s the greatest buy and hold investor ever, the greatest fundamental investor ever, and one of the greatest businessmen ever, he has seen his Berkshire Hathaway holdings decline by 50% twice in the last 15 years. If it can happen to him, trust me, it will certainly happen to you. I think that if there’s anything you can walk away with in this podcast is, learn more about measuring risk, learn more about hedging, and find a way to get your portfolio so that it has less risk than the market as a whole and can return, you know, around what the market is giving you. If you can do that, you’re gonna sleep a lot better at night and you’re gonna stick with your investments for longer, which is the real key to success.

Meb: There’s a monger [SP] quote along those lines where he says something like, “If you’re not comfortable watching your quoted shares portfolio,” meaning stocks, “go down by 50%, you have no business buying stocks at all.” You know, a lotta people they kinda think of that as a theoretical, but they never really, you know, say, “It’s not gonna happen to me,” of course until it does, then it’s a little more problematic.

Porter: I’ve also always told people that they should save at least $50,000 in cash before they ever buy an investment. And you wouldn’t believe the hoots and the howls, and the elitists, and the “You don’t care about the little guy” comments that I get. But the truth of the matter is, until you have the discipline to do that, you do not have the discipline to be successful as an investor, and you do not know enough about business. So trust me, do all the paper trading that you want, but save $50,000 before you buy a stock. I promise it’s gonna save you a lotta money in tuition, and by the way, why work hard at something? If you make 10% off $50,000, that’s 5,000 bucks. That’s worth doing. If you’re making 10% on $5,000, it’s not worth all the trouble.

Meb: Well, it’s funny you mention that because there’s been this huge development of a lotta these apps targeted to millennials. They’re raising tens of millions of venture capital dollars, and I’ve been a very vocal kind of critic on some of these, and there’s at least three very famous ones. And I say, “Look, you know, this is kind of on you, millennials. You just can’t do math,” because the average account size at three of these is like $100 or $200. And these apps, you know, they’re beautiful, wonderful user interface, they look really cool, they’ll take your deposits and savings and invest, but the average account size is around 100, 200 bucks, and they charge you a dollar a month. And so for $100 account, that’s 12% fee per year.

Porter: Meb, we’re in the wrong business. Let’s get into that business.

Meb: It’s a phenomenal business. I actually contacted three of them. Well first of all, I said, “Why wouldn’t I just start a free version of this and invest in our own funds and not charge any fees?” You know, the subscription model. But I’m also kind of…I was a little jaded. I was like, “Well the morons that are signing up, it’s kind of on you. If you’re gonna pay 10% fees to invest your money, then you kinda deserve it, I’m sorry.” You know, it’s…oh man. But the math doesn’t even work out until they get up above a certain amount. And again, going back to what you said, I firmly agree with you on the cash balance. And two, I also agree when you’re talking about risks and hedging, one of our favorite quotes, and I don’t know who this is attributed to, but is, “The best way to get rid of a risk is to not take it in the first place.” You know, people that put all their money in stocks or whatever it may be, you know, yes, you can hedge it through certain means, but two, also think about you don’t need to take that much risk in the first place. And the vast majority of what we see with financial advisors and registered investment advisors, is they put…and a lotta the robo-advisors now, they put people in portfolios that are far too aggressive for them to handle, which is tough to live through those sorta drawdowns.

The one comment I’ll make on the beautiful, useful, magical is…comes from my mom, who’s my number one podcast listener. And she used to have a quote, still says it, it’s basically, “Life isn’t a dress rehearsal,” meaning, you know, the time you spend every day doing what we’re doing… And look, we talk a lot about investing on this podcast, it’s the main focus, and spend every day of my life in this world and I love it of course, but also, you know, this is your only one shot you got at this life time. Porter, I know you do a great job of work-life balance as well. So that’s one of the things we talk about that I think people do a very poor job of, is they spend a lotta time optimizing how to make money and then invest it, and then very little time optimizing how best to spend it and enjoy it. Porter, any final thoughts, anything good you’re reading lately? What are you up to the rest of the year? Are you…

Porter: Yeah, I understand better now what you mean by your little beautiful, magical, thinking thing. And I will tell you that I think the real big secret to my success was that…it’s gonna sound hokey, okay, but I think there’s a lotta stuff out there, especially on social media, about “choosing yourself”. You know, James Altucher wrote that book about how you can develop your career. But I think there’s a lotta narcissism and a lot of self-centeredness on social media these days. And a lotta stuff I see is all about, “Take care of yourself first,” and that sorta stuff. And I have always had the exact opposite mantra. I’ve always chosen others. And, you know, you’ve been to my conferences, so you know I’m just…this is not BS. I built this business because I really thought that people weren’t paying enough attention to Steve Sjuggerud. Well that was a great way to launch our company. And we’ve been successful because I knew Steve was brilliant and I got the public to pay attention to him.

So it wasn’t about me. And, you know, I recruited David Eifrig for the same reasons. I knew he was a brilliant guy and I wanted the public to see him. And I’ve been a good partner, and I’ve been a good spouse, and I’ve been a good friend because you put other people first. And you just do that one foot at a time, day after day. And then all the sudden, you know what happens? You look back 20 years later and you’ve got all these people that really care about you and are willing to help you succeed too. That’s my thing. You talked about getting a job, whatever. It’s so easy. You deliver value for an entrepreneur and you volunteer to provide that value upfront, keep doing that and you’ll have a job before you know it. So choose others, that’s my magical thinking.

Meb: And not only that, but the behavioral research backs you up. You know, in a lotta people, the research shows that, you know, the money you spend on other people…of course we always talk about spending money on experiences rather than things, but also spending money on other people and doing things for other people gives you vastly more pleasure, and happiness over…and joy over time than actually spending money on yourself and particularly things. We’ll talk more about that on a future podcast, but I think that’s a great point. Oh Porter, and by the way, Eifrig, who will get on here at some point, too, and is an investment writer at Stansberry, is also now a wine maker. Have you had his wine? It’s actually really, really good.

Porter: It’s spectacular. I think it’s one of the best small wines being made in the United States right now. It’s really good.

Meb: I was fully expecting… Like, my brother used to brew his own beer and it was terrible. I mean, like, undrinkable. And so any time a friend is like, “Hey, I wrote a book,” or, “Hey, I’ve made some wine, can you try it,” I begrudgingly say, “Sure.” And his showed up and it’s actually phenomenal.

But so anyway, we’re gonna post show links to everything we talked about today. We’ll throw in some charts, as long as you let us. We’ll make some attachments to some of these publications, some of these quotes, everything else. And as always, Porter, thank you so much for taking the time out today, and I really appreciate the time we’ve spent chatting. And listeners, thanks for also listening. We welcome feedback, any questions to the mailbag at feedback@themebfabershow.com. And you can always find the show notes and other episodes at mebfaber.com/podcast. And you can always subscribe to the show on iTunes. If you’re loving it, hating it, whatever, please leave a review. Thanks for listening, friends, and good investing.

Sponsor: Today’s podcast is sponsored by the ride-sharing app, Lyft. While I only live about two miles from work, my favorite means of getting around traffic-clogged Los Angeles is to use the various ride-sharing apps, and Lyft is my favorite. Today, if you go to lyft.com/invite/meb, you get a free $50 credit to your first rides. Again, that’s lyft.com/invite/meb.