Nobody Wants to Read Your Shit…

No, this is not an email I received from an angry reader (though I have received many similar ones over the years). It’s actually the title of a fun book on the topic of writing that was published several years ago by the author of Bagger Vance and other titles.

Here’s a passage from “Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t” that explains the general takeaway:

“When you understand that nobody wants to read your shit, your mind becomes powerfully concentrated. You begin to understand that writing/reading is, above all, a transaction. The reader donates his time and attention, which are supremely valuable commodities. In return, you the writer must give him something worthy of his gift to you.

When you understand that nobody wants to read your shit, you develop empathy.

You acquire the skill that is indispensable to all artists and entrepreneurs – the ability to switch back and forth in your imagination from your own point of view as a writer/painter/seller to the point of view of your reader/customer. You learn to ask yourself with every sentence and every phrase: Is this interesting? Is it fun or challenging or inventive? Am I giving the reader enough?”

Before writing anything else, a quick apology…

As the author and/or editor of seven books, over a dozen white papers, and thousands of blog posts, it’s dawned on me that I’m a veritable shit-storm myself. So, thanks to all the survivors out there who are still brave enough to read my work.

Now, I’m going to tie all this into investing shortly, but for the moment, consider the enormity of the above passage.

If you ask someone to listen to a podcast, or read your blog (or God-forbid your 400-page book), that’s a huge ask. It’s expensive on a “time value of money” perspective, but also on an opportunity cost perspective.

What else could the reader could be doing with that time? Cooking dinner, hiking, learning a new language, working overtime, taking a nap, playing Fortnite, or spending time with loved ones.

Instead, they’re reading your shit.

Of course, they may not be reading your shit for long…

As the passage points out, this relationship between the author and reader is a transaction – the reader’s time and attention in exchange for the author’s gift of words.

Unfortunately, this transaction often breaks down. Why?

Well, consider the reasons most people want to be an author. They include, among others:

- Getting rich (LOL)

- Achieving fame and status

- Marketing a brand and building a following

- Enjoying writing so much that one simply must write

- Wanting to educate

- Wanting to tell a story

Now, why do most people pick up a book?

- To learn something new and/or interesting

- To experience enjoyment and pleasure (i.e. for fun)

- To escape from reality (i.e. avoiding your family)

Where’s the Venn diagram overlap between why writers write and why readers read?

Basically, wanting to educate (and learn) something new and interesting… and wanting to tell (and experience the enjoyment of) a fun story.

That’s it.

Most of the books that are written based on an author’s desire to make money, achieve fame, market a brand, and so on – they often fail to make good on the unspoken contract between writer and author – time in exchange for value. Many authors make the book about them, rather than writing for the reader.

The result? The reader puts down the book after a few pages and never returns.

Now, what does any of this have to do with investing?

Let’s make a few edits to the book title and the passage from the book and you’ll see…

Nobody Wants to Invest in Your Shit

“When you understand that nobody wants to invest in your shit, your mind becomes powerfully concentrated. You begin to understand that investing is, above all, a transaction. The investor donates his money, which is a supremely valuable commodity. In return, you the portfolio manager must give him something worthy of his gift to you.

When you understand that nobody wants to invest in your shit, you develop empathy.

You acquire the skill that is indispensable to all investors – the ability to switch back and forth in your imagination from your own point of view as a portfolio manager to the point of view of your investor. You learn to ask yourself with every sentence and every phrase: Is this return enhancing? Is it risk reducing? Am I charging too much? Am I giving the investor enough?“

Continuing the parallel, think about the reasons most investment professionals want to launch a fund and be a portfolio manager. They include:

- Getting rich (see recent Paulson quote)

- Achieving fame and status

- Marketing a brand and building a following

- Improving returns for the client

- Reducing risk for the client

Now think about the reasons most people want to invest in a fund. To be fair, there are many stupid reasons to invest in a fund (bragging rights, something to talk about, scratching a gambling itch, greed, fear, and envy), but I’m going to ignore those. There should only be four legitimate reasons to invest in a fund:

- Improving returns

- Diversifying and/or reducing risk

- Improving the chance of a positive outcome (i.e. helps you behave well)

- Reducing fees or taxes

Here too, we see only a small overlap in the Venn diagram.

It’s at this point that the comparison between reading a book and investing in a fund breaks down a bit. You see, when picking up a new book, whether or not to stick with it is a relatively easy decision – whether consciously or not, you weigh the other activities you might be doing with your valuable time, relative to how interested/hooked you are in the book.

If the book hooks you and delivers lots of pleasure, then it remains the center of your attention and the “to do” list will just have to wait. On the other hand, if the book doesn’t snag your attention, it gets tossed.

Investing is different…

The reality is that too many people remain wedded to awful holdings they should have sold a long time ago. Take a moment and think about what’s in your portfolio right now. Can you say, definitely, that every investment deserves to be in there? You’re certain of its benefit and value? (And if the answer is “I’m not sure” you might as well consider that a “no” for the purpose of this exercise. Go take our old article “The Zero Budget Portfolio” for a spin.)

This “put the book down” moment isn’t as clear to many investors for a handful of reasons – we become emotionally-wedded to certain investments, we see them lose tons of value and hold onto them hoping they’ll come back, we see them gain tons of value and hold onto them hoping they’ll gain even more, we buy based purely on the greed of riches from a “hot tip”…Often we forget the reason we bought the investment in the first place. The list goes on.

Given this challenge with booting an investment from of a portfolio, what should be our criteria be for “putting the book down?” Or alternatively, for even picking up the book in the first place?

Did you know there are over 10,000 mutual funds and ETFs? And that’s just in the United States.

We live in a world where you can essentially invest in the global market portfolio of stocks, bonds, real estate, and commodities for very low cost.

Let me repeat that, you can buy one, or multiple ETFs that will give you access to the global market portfolio. And this portfolio sets a very high bar for historical risk adjusted performance.

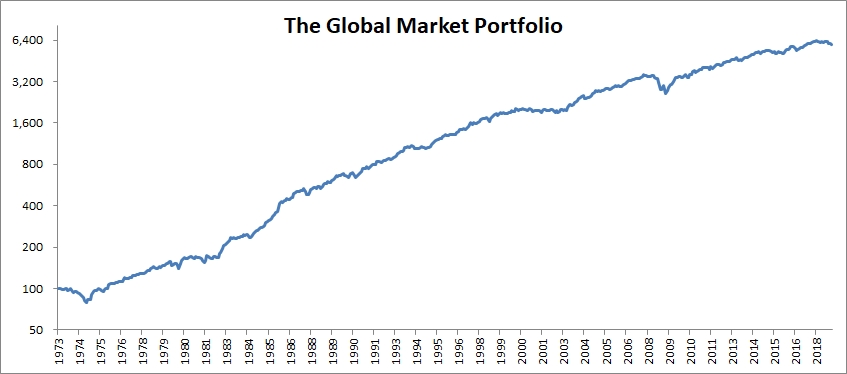

Historically this portfolio has returned about 9% per year, with 8% volatility, a 0.55 Sharpe ratio, and mild drawdowns of about -27%.

This global market portfolio becomes the investable benchmark “base case” portfolio.

So, as an investor, any new potential investment needs to clear one, or more, of the following four objectives to warrant an inclusion to this global market portfolio. (Likewise, any current investment needs to clear them to remain a holding.)

- Does the new fund improve the absolute returns of my portfolio?

- Does the new fund reduce the risk of my portfolio?

- Does the new fund improve the chances of my sticking to my plan?

- Does the new fund reduce the cost or tax efficiency of my portfolio?

That’s it.

Does your 2 and 20 tax-inefficient hedge fund check that box? Unlikely.

Does your flashy new thematic sector fund check any of the boxes? Fat chance.

What about investing in your cousin’s hot new startup? Probably not.

Taking a flyer on your neighbor’s favorite stock pick? No way.

My guess is that if you were to take your roster of funds and holdings and evaluate whether they hold up to the aforementioned objectives/criteria, most would fail.

This does not mean that the global market portfolio is the only reasonable choice for investors. Lots of asset allocations in our free Global Asset Allocation book are probably just fine.

Many times, I’ve also made clear my beliefs on value-add departures from this base case allocation. In fact, I clearly outline them in our white paper “The Trinity Portfolio”.

For example, I believe in tilting toward value, carry, and momentum, which check box 1 and perhaps 2. I also believe in trend following (boxes 2 and 3), tail risk (3 and maybe 2), as well as angel (1, 3, and 4) and farmland (2, 3 & 4) investing.

These departures from the global market portfolio work for me. I believe they are additive and worth the effort to include in the portfolio. However, I do my best to implement them in a systematic, low cost, tax-efficient manner. After all, building an automated process using tax efficient ETFs sets a very high hurdle for the addition of new funds and strategies.

Wrapping up, what’s important is that you find an investment approach that works for you. Yet it should set a high bar for after-tax and after-fee measures of risk and return. That way, when some fund manager pitches you the latest super proprietary, rigorous, high-tech alpha fund, you can politely reply:

“Hey bud, no one wants to invest in your shit”