Episode #267: Edward Altman, NYU, “We Had More Billion Dollar Bankruptcies In 2020 As Of September Of This Year Than Any Year Ever”

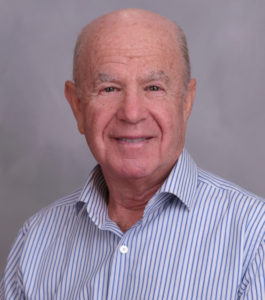

Guest: Edward I. Altman is the Max L. Heine Professor of Finance, Emeritus at the Stern School of Business, New York University. He is the Director of Research in Credit and Debt Markets at the NYU Salomon Center for the Study of Financial Institutions. Prior to serving in his present position, Professor Altman chaired the Stern School’s MBA Program for 12 years. Dr. Altman has an international reputation as an expert on corporate bankruptcy, high yield bonds, distressed debt and credit risk analysis. He is the creator of the world famous Altman-Z-Score model for bankruptcy prediction of companies globally.

Date Recorded: 10/27/2020 | Run-Time: 52:23

Summary: In today’s episode, we’re talking corporate bankruptcy, high yield bonds and credit risk analysis. We talk to Professor Altman about the Altman Z-Score Model, which he created in 1968 to predict bankruptcies. He discusses the record high debt levels companies had at the end of 2019 right before COVID hit the U.S. and what he’s seen this year with a large number of billion dollar bankruptcies. He also touches on the jump in the rate of zombie companies around the world.

As we start to wind down, Professor Altman explains why he is bullish on high quality junk bonds and why the happiest moment of his career was testifying in front of Congress in 2008 advocating bankruptcy for GM.

Comments or suggestions? Email us Feedback@TheMebFaberShow.com or call us to leave a voicemail at 323 834 9159

Interested in sponsoring an episode? Email Justin at jb@cambriainvestments.com

Links from the Episode:

- 0:40 – Intro

- 1:38 – Welcome to our guest, Edward Altman

- 5:32 – Where credit scores stood at the time of their creation

- 8:22 – A broad overview of the model

- 11:04 – How the model has changed over the years

- 14:58 – Driving forces that have pushed more companies away from AAA ratings

- 17:46 – How Covid has impacted corporate debt levels

- 18:00 – His papers

- 25:52 – How Fed actions have impacted markets and what future unintended consequences could be

- 32:08 – Global debt situation

- 35:23 – Any specific countries worth keeping an eye on

- 37:59 – Quality junk bonds

- 41:11 – Status of negative yielding sovereign debt and the chances we see it in the US

- 45:41 – Problem with propping up vested interests

- 47:10 – Ideas that Professor Altman is interested in today

- 49:15 – Most memorable investment of his career

- 51:20 – Connecting with Ed: website, Corporate Financial Distress, Restructuring, and Bankruptcy: Analyze Leveraged Finance, Distressed Debt, and Bankruptcy

Transcript of Episode 267:

Welcome Message: Welcome to the “Meb Faber Show” where the focus is on helping you grow and preserve your wealth. Join us as we discuss the craft of investing and uncover new and profitable ideas, all to help you grow wealthier and wiser. Better investing starts here.

Disclaimer: Meb Faber is the co-founder and Chief Investment Officer at Cambridge Investment Management. Due industry regulations, he will not discuss any of Cambria’s funds on this podcast. All opinions expressed by podcast participants are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of Cambria investment management or its affiliates. For more information, visit cambriainvestments.com.

Meb: Hey, friends. Another great show for you today. Our guest is a professor at the Stern School of Business at NYU, and one of the preeminent experts on corporate bankruptcy, high yield bonds, and credit risk analysis. In today’s episode, we learn how our guest created a model to predict bankruptcies way back in 1968, called the Z-score when computing power was a bit lacking. The model’s evolved over time, but it’s still widely used to this day. We get into the record-high debt levels companies had at the end of 2019 right before COVID hit the U.S. and what our guests are seeing this year with a large number of billion-dollar bankruptcies so far. We chat about the jump in the rate of zombie companies around the world and our guest goes on to explain why he’s bullish on high-quality junk bonds and why the happiest moment of his career was testifying in front of Congress in 2008, advocating bankruptcy for GM. All this and more with NYU Stern’s professor, Ed Altman. Ed, welcome to the show.

Ed: Happy to be here, Meb.

Meb: I am super excited to have you on today. You’re in New York, I’m in Los Angeles. And before we get started, I wanted to ask you a question about 2020, which we’ll come back to. I had heard in a different presentation that you have a bit of a tradition with your wife involving wine and champagne, and I want to know how your 2020 is going because at the sounds of it, this might be kind of a boozy year for you guys.

Ed: You’re quite right. My wife and I, we opened up a bottle of fine red wine when there’s a big bankruptcy. If there are two or three in a short period of time, we move to the fine champagne. And in certain years like, ’01, ’02, ’08, ’09, and certainly earlier this year, Meb, we were drunk all the time.

Meb: Pandemic is a good excuse, Ed. I think that’s fair. Let’s rewind. I want to go back to when you used to be in the land of milk and honey, Los Angeles, right down the road from me. You were doing a PhD in finance and pre-computers, this may have been mainframes. And I’ve heard you talk a little bit about this, about how the timing was a bit fortuitous, congrats on your 50-year anniversary, by the way, of coming up with you, call it the Z-score, the famous Altman score. Tell me the origin story. The audience would love to hear it.

Ed: I was very, very fortunate, Meb. I was a PhD student at UCLA in the mid-1960s, very lucky that mainframe computers were becoming available on college campuses for social science research. They usually were there for the Cod sciences, medical sciences, but very little before that for us in the social science area, economics and finance. And also, I was lucky that there was a young assistant professor there and he mentored me a bit on using a technique called discriminant analysis to discriminate between healthy companies and sick companies. And I’m absolutely convinced that if I was a PhD student two years earlier, I wouldn’t have had the computer power. Even though it was quite new, I wouldn’t have had it to do the kind of multivariate analysis that we did. And two years later, probably someone else would have beat me to it. So, you know, timing is really important. And I must admit, and this may sound maybe false modesty, but it’s not. I’m really surprised that a model, econometric model, statistical model has lasted more than 50 years. Usually, the half-life is just a couple of years and then there’s a better mousetrap out there. In this case, for a number of reasons, I believe, it has survived and is actually more popular than ever. But back then it was the stone age for doing financial research. No databases. You had to gather the data yourself, transform and on. I don’t know if you have ever heard of something called punch cards. Most people who don’t have grey hair or thinning hair probably never heard of it, but you had to punch it onto these cards and you had to put them in these boxes, carry them across campus, deliver them to the mainframe mother computer, and then you’d pray that you got results. And half the times the prayers were unanswered so you had to do it again, a Cod that was bent or you punched data in the wrong field. You eventually were able to do models and test them. The only data sources or those big, fat heavy volumes called Moody’s industrial manuals and you had to somehow go in there. The balance sheets and the incident statements weren’t very good. Very few firms went bankrupt then so the sample sizes were small. As I said, we were really lucky to build a decent model and it somehow has stood the test of time.

Meb: It’s funny you say that because as you think of, you know, we’re in a modern world where you can just click and hit a button and come up with any sort of back-tested simulation., and so many of the academic research shows that that’s what people do. You know, they find some combination and then turn it into a fun. But if you think back to why yours may have stood the test of time, it actually makes sense because the concepts not necessarily based on just fitting the data to the past, but rather intuition and how people thought about maybe a hypothesis of what had worked up until then. And what was the status of sort of credit scoring at the time? Was it just sort of a little bit of intuition?

Doug: No. I guess we had fairly good data on traditional, what’s called traditional financial analysis from the rating agencies. Moody’s 1909, S&P 1916, some progressive companies like DuPont had their own internal systems that were pretty decent, but they were looking at traditional measures one at a time. And even some pretty decent studies by Bill Beaver who was at Chicago at the time, now is on the faculty at Stanford, so he’s an old-timer like myself, were pretty decent, but they were traditional, one financial measure at a time. The thing that we introduced were two main innovations. One was looking at a number of indicators simultaneously, using and harnessing the computer power to identify the appropriate weightings as their relative importance. And the other thing that we were able to do for the first time in credit was to utilize the information content of stock market value indicators. That was made more popular a couple of years later in the early ’70s, ’74, I think it was. Bob Merton work on continuing claims using a technique that involved market measures, volatility of stock price, historical analysis on that as well as get levels. But we were the first to actually introduce market value of equity as a important measure of the credit risk of a company. Before that, they only looked at standard credit ratios, put it all together and out came the Z-model or Zed model, which at that time I was just happy to get my PhD and get the hell out of there. You know, I had a job at NYU and somehow I’m still there after 53 years. Born and raised in New York, but I love Southern California. I didn’t want to necessarily leave, but one of the few jobs that was offered to me. And so that was my objective, but somehow it has lasted. And I can give you maybe three reasons why I think it’s still around?

Meb: Give us for the audience who’s not familiar. Give us just a broad overview of the actual inputs. And I know there’s a whole family and there’s been some evolution, we can talk about that. But give us a broad overview of the model in general and then, yeah, I would love to hear why you think that stood up.

Doug: First of all, the model involves five financial indicators. Most of them are traditional, measuring liquidity of a company, profitability, leverage, operating efficiency. But in addition, we looked at cumulative profitability, so the retained earnings of the company, and also this market equity relative to the debt of a company as a measure of the leverage and how much support they were getting or not from the stock market. And then you put those indicators together and you let the computer algorithm choose the weightings and out comes an equation. One of the beauties of it is a pretty simple equation. You could do it with a handheld calculator and a balance sheet and income statement. You don’t need a computer to calculate a z-score on a company in about 30 minutes’ time or even less. But you don’t have to do that anymore. You can go to a Bloomberg terminal, you can go to Reuters, you can go to Capital IQ, you can go to any number of software programs and they’ll give you the Z-score so you don’t even have to calculate it now, but that wasn’t the case then. So being simple really is a great virtue if it’s fairly accurate. We think that today the Zed model with a Z-score that I would say today is if it’s zero or below happens to be the latest cuddle score that I like to use is about 80 to 90% accurate within two years of the bankruptcy. You can get false negatives, so to speak. And those are firms that look like they go bankrupt, but they don’t. And that is something we can perhaps pursue a little bit later, Meb, because that’s an evolutionary phenomenon in our economy. There’s lots more bankruptcies, no question about it, but there’s also lots more restructuring out of court that a lot of people not familiar with. And the third reason, it’s free. You don’t have to pay for it. You know, somebody offers you a cough drop and you try it and you say, “Oh, I like it or I don’t like it,” and then you might buy more. Well, same thing with a model. If you don’t have to pay much for it or nothing, you can try it, see if it works, and then discard it or keep it. I think those are some of the reasons. Now it’s almost a generic model because people are… They may not be familiar with the old calculations, but they are familiar with the track record, and that’s really very nice.

Meb: Tell me… You know, in the ensuing years, just hit its 50th anniversary, you’ve given speeches all over the world and become very famous for this model. How has the thinking changed? You mentioned that there’s a lot of evolution in the credit markets, certainly, and then so many decades, little guy down the street from me, Milken, certainly stirred up that market quite a bit in the decades post-publication. How’s it sort of evolved over time, how has your thinking evolved?

Doug: First of all, you’re quite right in implying that there’s been an incredible evolution migration of credit risk in our economy. Back when I built the models in the ’60s and certainly for a while after that, there were no high yield bonds, no junk bonds, no Michael Milken, no leverage loans. And now it’s a big industry, close to $2 trillion in junk bonds, about the same in, now $1.4 trillion in leveraged loans. There’s a little shadow banking as well as the regular banking out there. So altogether we’re talking about well over $3 trillion worth of leveraged finance in the system, and there was very little back in the ’60s, so you had a lot more leverage now. Also, you have global competition far more than you had then. So while it’s easy to enter today, it’s also very easy to be knocked out by a competition globally. Interestingly enough, you know, how many people are aware of this, the average credit rating is much lower than it was then. Take a guess at how many AAA companies there were, say back in the early 1990s and how many they are today. It’s true that there are two left. One is shaky, but it’s still there, Johnson and Johnson, and Microsoft probably will be the last one if Johnson and Johnson gets downgraded. They are the two AAA’s, very relatively few AA’s. I did an informal survey. I actually started when I had the great luck to be asked to do a visiting professorship just outside of Paris in the early ’70s, and I started doing these informal surveys, asking corporate treasurers and CFOs, “When you grow up, what rating would you like to be?” And the usual answer over the last, say 30 years or so was A, A-rated, maybe AA. Even then people thought AAA’s was kind of a false benefit for most industrial companies because of the lack of leverage and its impact on earnings per share, A was the popular one. Today, it seems to be BBB, and BBB while still investment grade is right on the cusp of being downgraded as a fallen angel. My point is that there’s so much more leverage in the system that the average Z-score has come down since the mid-60s despite the fact that the economies are much larger, more robust, you didn’t have those tech giants that we have now. Overall, however, the average rating is lower and the average Z-score by bond rating is lower. And so I adjust my bond rating equivalents of the Z-score for these trends rather than build a new model every two or three years, which a lot of people say I should be doing. I’m not as hard-working as my colleague, Aswath Damodaran who keeps his amazing website up-to-date for me to redo my models every couple of years and put it out there in a blog or something. Maybe I should have been doing that, Meb, but I don’t. So I try to take advantage of the fact that it’s a robust model, still quite accurate, but to change the meaning of the Z-scores, I found it really effective, and maybe we can get to this in analyzing what’s going on in COVID-19 in 2020.

Meb: I wanted to touch on something you were talking about right now just because I’d love to hear you elaborate, which is the original model, the focus was on manufacturing companies. And you mentioned the credit changes over the years, obviously, the Milken influenced the issuance. I mean, I wonder how much of the move from AAA to kind of lower levels, how much of that is due to just changes in the economy and sectors, more service-based more tech-based, but, but also how much of it is this company is sort of C-suite relentless pursuit of profitability. I think a lot of people would say, “Well, AAA just means you’re underleveraged. You should actually want to lever up.” What are the main driving forces do you think that have pushed this, and are they good things? Are they bad things?

Ed: Lots going on. As I said, one is fundamentally more leveraged and when you have more leverage, it’s harder to keep those AAA ratings or even AA. A second is more competition. If you’ve got a really good product, in most cases, you know, there are exceptions like Walmart maybe an Amazon, you get a lot more competition and it’s harder to keep those profitability ratios and levels high. And I mentioned this before about the global situation. No longer are you only competing with a, relatively few companies, there’s been a transition in sectors. Oil companies are no longer in favor. They were, you know, these giants back then, nobody could touch them. Now they are vulnerable. Lots of things going on. But I think the main reason, to be honest with you, is more leverage in the system. More than any other factor is why the credit numbers are lower despite the fact that the stock market is much higher. And don’t forget, one of my measures is market value of equity. In fact, my academic colleagues would probably argue, well, if you look at the debt-equity ratio of companies, it’s not any higher. I agree with that. If you look at debt-equity and you measure equity and market value terms, the debt-equity ratios are not that much higher than they were 20 years ago. But periodically, we get these big drops in the stock market such as March of this past year. So I simulated the impact of a 20%, 30%, and 40% drop in the stock market on aggregate debt-equity ratios. Except for 2008, 2020 was at the highest level that I can ever remember in terms of a lot of leverage relative to equity. And so that’s always a factor, whereas yeah, we had periodic drops in the stock market in the past, of course, but people weren’t as focused on the equity market value as they are now. And now you’ve got to look at not only the level, but the volatility and what could be to level in the next downturn.

Meb: We have somewhat emerged from this very just sort of mellow period this past decade, particularly with the U.S. stock and bond returns, really U.S. anything relative to the rest of the world, for sure, post-financial crisis. I was reading a couple of your papers, we’ll link to them in the show notes last night. You’ve been very prolific and continue to be, in this one you and recently about 2020 in COVID, I thought it was really thoughtful. Kind of walk us through your thoughts coming into this year. What were some of the signs and ideas of credit markets and then how that has changed at all in 2020, if anything?

Ed: You’re absolutely right to focus first on what was the situation before COVID-19. I’ve been saying that for a couple of years now and looking at each year and saying, “How vulnerable were we to a big credit meltdown if we had some catalyst without knowing what the catalyst would be?” So at the end of 2019, the corporate debt level, except for financials, so non-financial corporate debt as a percentage of GDP kind of like a debt to cash flow ratio for the economy was at a record level. And every time we’ve had peaks in that debt to GDP level, within 12 months, it was followed by a peak in default rates and bankruptcies. So I looked at 2019 and I said, “Okay. We’re at a new peak.” And I think it was close to 50%. Non-financial corporate debt was close to 50% of the 22 trillion in GDP. Well, over 10 trillion. And I looked at that and I said, “What would be the impact of a downturn?” And we simulated it and it was going to be the highest default dollar amount ever. And nothing happened until March, essentially in the U.S and then the bankruptcy started piling in one after the other. Yes, I was drinking a lot of red wine and the like, but seriously, we had more billion-dollar bankruptcies in 2020 as of September of this year through three-quarters than any year ever. We had 51 of these billion-dollar babies and like 150 or so, more than 100 million in liabilities. And the highest year ever was 2009. Before, we broke the record of billion-dollar bankruptcies in September and we will break the $100 million bankruptcy level probably this month, although it has diminished of late, there’s an article on “Wall Street Journal today” just about that, and I can get back to that too. But the point was, we were vulnerable in ‘019. So at the end of 2019, the average Z-score was actually about the same as 2007, a year before the financial crisis. So we hadn’t really improved, at least from this holistic z-score approach despite the fact we’ve had 11 years of this benign credit cycle since the great financial crisis, companies’ growth has been dramatic in many, many sectors, despite all that because of the increase in leverage, the average z-score has remained about the same. To me, that was indication that we were as vulnerable in 2019 as we were in ’07. And don’t forget in ’07, it was risk on and in ’19 it was risk on. Ironically, Meb, it’s risk on again today in the pandemic. And so my conclusion was we were quite vulnerable. And sure enough, we had the pandemic. Okay, that’s unprecedented. But so was the stimulus from the government. So was the Fed’s actions and remarkably, the market’s turned around, but not the real economy so much. And bankruptcy’s piled up and defaults. A lot of them would have happened if there was some other catalyst. It wasn’t the pandemic that was the cause of a lot of these companies’ filing.

And then there was the BBB phenomenon. This was actually an interesting sidelight for a lot of people, but not for me back in 2019. I had this running debate with the rating agencies, and I still do, by the way, that was talking about the vulnerability of the BBB sector in 2019. I was concerned with the amount of fallen angels, downgrades to junk, then being quite high and the rating agencies all said, “Don’t worry about it. Maximum of 10% downgrades over maybe a two to three-year period in the next downturn.” And I said, “Well, let’s take a look at the quality of these BBB’s rather than just talk about them being investment grade or letting them to remain investment grade.” And so we looked at the Z-scores and we calculated what’s called a bond rating equivalent, and that is a score and it’s relevant bond rating according to our analysis, not according to the rating agencies. And 35% at the end of 2019 of all BBB’s, and we’re talking about 400, 500 companies did not look to me like they were BBB quality, they looked BB and B. So I said, “Okay. Well, how many of those are actually going to be downgraded in the next downturn?” And I thought it would be a lot more than 10%, but certainly not 35% because rating agencies don’t necessarily look at models. They have many other criteria. And let’s face it, I think they do a pretty good job on the rating of companies, but they don’t do a very good job on the re-rating of companies and they take a long time to downgrade and they don’t downgrade enough when they do downgrade in my opinion. At any rate, I said around 20%, rather than 35% would be downgraded. That’s about $600 billion over the years, 220 and 221. The rating agencies said maybe 10%, which would be about $250 billion to $300 billion. If 600 million get downgraded to junk, that increases the junk market by about a third or even more, and that I think could have some profound effects on the market, so-called crowding out of the lower-quality companies. So, fast forward to 2020. I wish I had a PowerPoint slide to show you the list of downgrades and what the Z-scores were. But every one of them, and we’re talking about 20 to 25 companies had a Z-score that was a bomb rating equivalent below BBB. Every one of them, Ford, Occidental petroleum, Macy’s, Marks & Spencer, Pemex, Royal Caribbean Cruise Lines and many more all did not look to me like investment grade even in 2019. Now so far about 200 billion have been downgraded, one-third of what I thought would happen by the end of 221. So we’ll see what happens. The rating agencies may still be right. I don’t think so. But anyway, that’s a way of applying a model to something that the market is influenced very strongly by the rating agencies. And that is an issue for investment managers to keep in mind, you know, who’s right, models or the rating agencies? And what does that mean about your investment dollars? I happen to believe in a concept called quality junk, and we can get into that. In fact, I’m hoping to come out with a fund dealing with that very soon.

Meb: I definitely want to hear about that. I wanted to touch on one more question while we’re kind of on this topic, which you alluded to, there’s a lot of forces washing around. You have, on one hand, the typical creative destruction of markets and capitalism and companies competing with each other, not just domestically, but globally. I mean, you mentioned energy, which I think the equities at one point as a percentage of the S&P were 30% and now they’re at 3%. And so they’ve seen a pretty widespread over the years, but also this pretty big influence of government. And so you have the two levers, of course, of fiscal and monetary policy and a lot of commentators, and our listeners, and really participants, in general, aren’t really sure what to do when it comes to government’s involvement. It’s through those various levers and how they’ve responded to the financial crisis, how much of that is a good thing, and much of it is staving off the inevitable. I recall you got to talk to a lot of the politicians back in the day when GM was going through some of its issues. Any general thoughts?

Ed: Very concerned with unintended consequences of the Fed and the stimulus, but particularly the Fed actions. First of all, kudos to the Fed. They stepped in quickly and dramatically in March and did unprecedented things in terms of purchasing them in bonds, of course, corporate bonds, even fallen angels, supporting CLRs, collateralized loan obligations, ETFs, and it worked. I would guess Chairman Powell and Vice Chairman Clarita are pinching themselves saying, “Wow. I didn’t think it would work so well.” And so kudos to them. It was much faster and more dramatic than certainly what happened in ’08, ’09, which also worked, but it took longer. However, it has created this incredible risk on atmosphere. Yes, interest rates are low. And so that is positive for companies are raising debt and saving off defaults in many cases. Yes, the markets have come back. A lot of portfolios now are not as much underwater. Although the S&P is really misguided for many investors, given that it’s heavy emphasis on technology. But at same time, we had issued more junk bonds by the end of September, let alone today than any year ever. The past biggest year was 2012 when it was just around $330 billion. Now it’s more than $360 billion. Investment-grade debt going through the roof. So the leverage in the system has increased and I don’t see… And even CCCs now are getting a big play. So I don’t see that diminishing very much as long as these interest rates stay low and corporate treasury say, “Hey, I’m going to take advantage” and invest the saying, “I’m looking for yield.” But what is creating is a bubble in debt rate ratios, which won’t be a problem as long as companies are able to cover their debt level. I don’t know if you know the concept of zombies in the economy, if you’ve heard that term before, Meb. It’s a somewhat of ambiguous definition, but let me give you one study and the trend of that study. And I’m doing some research and some of my colleagues at NYU are looking into the zombie effect globally. It started in Europe quite a bit. It’s not a pandemic, but what it is is companies artificially being kept alive in one form or another. Banks, governments. When companies look like they should go bankrupt but they don’t. They can’t their interest payments so they give an interest-only loans, etc. Well, this study by Deutsche Bank looked at the percentage of listed companies that have been around for at least 10 years who have not covered their interest payments with earnings for the last three years. And that ratio went from almost zero 15 years ago to 20% today. Twenty per cent of the companies that they looked at have not covered their interest payments. In other words, their coverage ratios are less than one for the last three years. I’m not sure that’s the best definition. I like to look at very low-rated companies with Z-scores that say they’re going bankrupt, but they don’t for, let’s say, at least a year or two.

And usually, they also are companies that are not covering their interest coverage. They’re not covering their interests as well. There are others, the OECD’s and the BIS have definitions, but the point is with so many more zombies in the economies of the world, it’s just like kicking the can down the road. These companies for the most part will not survive. They’re just being kept alive artificially, which is not healthy for the recovery of the economy. At least that’s my opinion. And we have too much debt and somehow or other in a pandemic. And, by the way, a recession since February, we are adding leverage like never before. Every other crisis I’ve looked at, you had a de-levering mandated by either legislation or by good sense. But in this one, it’s re-leveraging. I can understand some companies doing it to make sure they have enough cash to hide them over, so to speak, solvent, even in a continuing downturn in the economy and their sector. They’ve overdone it. Some companies, maybe there’s a silver lining here, and I’ll tell you what that silver lining could be. And that is start paying down your debt when you can. Use that excess cash to pay down your debt. Float new equity when prices are high again. Don’t wait for the market to turn negative again before you try to issue new equity and bring those debt-equity ratios back to some reasonable target level before it’s too late.

Meb: It seems so sensible. I mean, I think a lot of individuals during the crisis have re-learn that lesson with the way things have been this year. You referenced zombie companies. I mean, Japan has famously been known for kind of that concept over the years. Their equity market is just now in the last few years, getting back to where it was in the 1980s. You get to talk to and chat with investors all over the world, the U.S. just finished off this beautiful decade of returns in the financial markets. For the rest of the world, not so much. Do you have any general view on what sort of the debt situation looks like globally and also with a nod to sovereigns too? We didn’t get into much sovereigns as much today, but what’s the rest of the world look like?

Ed: It’s much the same picture, although not as dramatic. There are four main categories of debt that you can look at globally. Non-financial corporate debt, financial corporate debt, banks insurance companies, brokerage firms, government debt, and household debt. And each one of those has had its level increased dramatically in the last 20 years. Some of them have stopped increasing like financial company debt mainly due to the crisis of ’08, ’09, and in mandating by BIS of more equity in their capital structures. Household debt, it depends on the country. U.S. has come down from what it was at its peak that motivated the financial crisis in 2008, ’09 but non-financial corporate debt globally has increased about 60% of GDP globally to 93% in 2019. I don’t even have 2020 numbers. Government debt. The government debt is already very high and we’re going to have to finance this pandemic support sooner or later, those government deficits have to be dealt with. And the inflation is possibly going to be creeping back into our system maybe quickly as a result. So I’m concerned globally. I do have a measure of sovereign risk, by the way, which most people have never thought about. The traditional methods are looking at macroeconomic factors, the government debt to GDP, unemployment productivity, trade deficits. In 2011, I published a paper with good colleague from the Netherlands, Herbert Rijken, on a new measure of sovereign debt default risk. And what we look at is the health of the private sector within the country. If you combine that with the health of the banking system and the macro figures, I think you’re going to get a better holistic approach to analyzing sovereign health. We’re hoping that that will somehow get into the rating agencies. I think they look at it somewhat but not enough criteria and it will get into the financial markets. And they’ll look at average Z-scores, sent that are high probabilities of defaults, and you can learn a lot from that picking up pricing.

Meb: This is really thoughtful idea that I actually hadn’t seen that much in the literature before. You’ve kind of written about it and we’ll again, listeners, we’ll put it in the show note links. Are there any standout countries that look a little worrisome or look particularly in cloud here in 2020 that I imagine we could probably guess some of them, but any of them come to mind?

Ed: I’m embarrassed to say I haven’t looked in 2020. I’ve been so focused on the U.S. but let me tell you, we forecasted a down decline in Brazil about two and a half years before they have their recent problems. And they’re still in trouble there. It’s very clear that countries like Greece, Portugal, Italy, and Spain were having huge problems in that private sector. When their credit default swaps, that’s a measure of default risk in the capital markets, the cost of insurance on default risk at the sovereign level were more or less the same for those countries as other European countries. Maybe not Germany, but most of the other ones. That was because of the implied bailout that the European Union had for those countries. But we were saying they look really, really risky back in 2009. More recently, Russia will look pretty sick to us. Brazil, as I said. India was beginning to crack open in terms of the health of their private sector, the bigger firms that we can get data on. Korea, back in, when was it? Nineteen ninety-seven. The country in all of Asia that looked the weakest to us was South Korea because their private sector was so risky, had so much debt. And guess what their bond rating was? AA-. And the reason why they were double AA- was they’d been growing at 10% GDP or more for about a decade. But we weren’t looking at the aggregate growth rate of the economy, we were looking at the health of the private sector and they were so heavily leveraged and they had been, you know, government subsidies throughout low-cost debt. But even then they were very, very leveraged. So just an example of how you can gain insights by looking at a non-traditional sovereign indicator like the private sector.

Meb: Asian flu had a different meaning in the 90s than it does today as a markets, what you mentioned, I think ’97. Man, some of those markets absolutely got pounded in the late 90s. You have a curious mind, you continue to think about markets ideas. You made a quick reference to quality junk. Let’s talk about that. What’s your idea there?

Ed: I think junk bonds are fantastic. I’ve always thought that we went back to the Milken days when I had the good fortune being asked by Morgan Stanley at that time to analyze whether or not they should get their hands “dirty” with junk bonds. You know, it wasn’t as well thought of then as it is now. And so I got involved and, of course, we had to disassociate ourselves with the research coming from Drexel because they were the market leaders and we wanted an objective different opinion. And so I decided to look at the risk-return trade-offs of these bonds and I looked at default rates, etc, and I followed it through the years. And one thing I noticed was you could do even better maybe by 1%, 2% a year with half the volatility if you eliminated defaults in your portfolio. Now, that might sound so obvious and trivial, but it isn’t because if you buy an ETF of junk bonds or you invest in an index or some sort of overall diversified portfolio, you’re going to get, I don’t know, over the last 20 years, 300-plus defaults, maybe more, 350. But if you can eliminate them or reduce them dramatically, you’re not going to get hit with bonds going from par down to 40 or the loans going from par down to 60. And so what we’ve done is put together a number of filters or screens. Obviously, I can’t give you the secret sauce completely, but let’s face it. There are a number of filters that you could rebalance your portfolios over time to just about eliminate defaults if you were disciplined and you didn’t base it on the market sentiment, you based it on hard, empirical data. So we’re trying to do that. And I think we’re succeeding quite well a bit. We’re coming out with a fund probably in January, but it’s in Europe first. It’s like before you go to Broadway, you got to try it on the road and then hopefully we’ll issue it in the U.S. And I’m working with a boutique firm called Classes Capital in Milan to put the finishing touches on our back testing. This is crazy, Meb. Here I am. Let’s just say no longer a chicken, young chicken, and getting involved in a new venture like this, this is crazy. I should be sipping wine and sitting on the lake and fishing, but I’ve always tried to think about maybe putting to work some of my ideas in a different way than wising, but actually doing. So, we’ll see what happens.

Meb: When you’re ready to do an ETF in the U.S., hit us up. We’ll help you out. Last podcast we just published was on the topic of how to launch a fund. We will love to keep you forever, but I’m going to start to wind down with a few ideas and kind of quicker questions. You mentioned Europe. And if you were to ask me 10 years ago and say for the last financial crisis or thereabouts and say, “Meb, 10 years from now, the world is going to be a little different-looking in a lot of bonds around the world and the sovereigns have negative yields. There’s even a corporate or two out there.” And then, including in some countries, I think it’s Denmark. I can’t remember where. “You can get a mortgage with a negative yield.” I would’ve said you’re crazy. What do you think about that sort of status? And then two, do you think we ever see them in the U.S., negative-yielding say 10 years or bonds in general?

Meb: I wouldn’t eliminate that possibility because we said it couldn’t go down to zero, which was very early this year. It’s a little higher now. I don’t think we’re going to have negative nominal rates coming up because I do think inflation is going to pick up, even though the Fed is going to try to keep interest rates low. Negative real rates are definitely maybe here already or will be here with inflation picking up and the interest rates staying below 1%. So, you know, negative real rates for sure. I too scratch my head, Meb, about the European and Japanese situations of negative rates. I can’t understand why you pay people to hold your money, but we even had negative oil prices for a while because of that situation. But oil is different than dollars or sounds, or maybe it was the dollar situation. So I’m no expert on this stuff. There are probably a lot more competent people who studied interest rate movements over time, you might ask a guy like Jim Grant something on that and me, but I have trouble with that concept. And it’s, I think a real problem for people my age, who are trying to change their portfolios to fixed income, you know, as we get older, and we’ve always been taught that, and we can’t get anything, maybe that’s why the stock market is doing as well as it is, people just saying, “Hey, I’m not going to put my money into fixed income products unless there’s a lot of risk there.” Maybe that’s why we’re getting so much risk.

Meb: It’s not just individuals you mean, you’re talking about all the pension funds and endowments and real money sovereigns that are struggling with a lot of the things you’re talking about as well.

Ed: Absolutely. Right. So I’m no expert on this as I said, but I just know it’s driving me crazy to see the kind of yields that I get. So what do I do? And then I start buying, “Okay, I’m going to get high-dividend paying companies.” And then you read in the newspaper, well, even they’re not doing well because they’re doing worse than stock market in general. But I’ve always believed in moving your money to where the interest rates are higher, assuming that you’re not taking undue risk, but maybe we’re taking too much risk now to do that. So that’s part of it. To change the area, you mentioned something and I have to mention it, in all my years looking at 50-plus years of Z-scores and what have we learned, I must tell you the anecdote of, I think, the happiest day in my professional life, if I can interject that before we leave. And you mentioned the GM situation. I just keep thinking that what would GM be like if they didn’t go bankrupt in 2009? I think back to my testimony to Congress in 2008 in December where I was the only one who advocated bankruptcy as opposed to the other B word, bailout, at that time. And I’m convinced that the loan they got from the government, the fact that they were forced to restructure in a dramatic way, that balance sheet and somewhat their operations from the chapter 11 process is what saved that company. The Z-score was clearly saying they were headed for bankruptcy. And you mentioned opening up a bottle of wine. I don’t know how many days I was drunk after June 1st, 2009, when they finally filed, but it was like finally the company and the government realized that you can’t keep bailing out these companies that were hemorrhaging so much cash every day, every week, every month. That was very unpopular with the Congress when we use the bankruptcy word, they didn’t want to hear it, but it worked.

Meb: It’s the same because it’s been such a natural part of the cycle of corporate destruction for hundreds of years were out with the old and in with the new and that’s what makes a country and an economy vital and vibrant rather than just propping up old interests. But that’s the problem, is you get people with vested interests, and it’s also hard. You have these industries, and towns, and cities, but again, you know, we’re not investing in buggy whips and telegraphs anymore and you can’t argue that that would have been smart to prop those up 100 years later either.

Ed: In bankruptcy, a chapter 11, federal bankruptcy, you can close dealerships a lot easier than when you’re not in bankruptcy. There were 5,000 General Motors dealerships in the U.S. and they were being outsold by Toyota which had 2,000. There was no way you would enclose those dealerships on the state law until you go bankrupt. That was just one of the many issues. Anyway, sorry for interjecting that. But it is where you have a model that can help you. You remember William Shakespeare said to file or not to file. That’s the question. Well, a board of directors has that responsibility and they were not psychologically ready to file for bankruptcy in 2008 or ’09, until they were forced to.

Meb: As we look out to this new decade has been quite an eventful year thus far. Anything else that’s on your brain, particularly curious, confused, interested, excited about in markets, either corporate, or global, equities, bonds, anything in between? Anything you’re thinking about?

Ed: I must tell you that I’ve had more students interested in taking my course this year than in a long, long time. And so they’re interested in getting jobs, of course, but also they see that restructuring, how do you restructure companies. I’m really focused on that lately, using analytical techniques to help in the restructuring as well as the traditional chapter 11. I’m excited about that possibility. What I’m telling students is there be a second wave of defaults and bankruptcies coming. And one thing that’s really, really surprising to a lot of people, and it was to me at first is how many less people are filing for bankruptcy in 2020 than in 2019, how many low, less small and medium-sized firms of actually filing for bankruptcy. And then the question is, is there a short-run issue? Is it because of the government stimulus, etc? Direct loans, payroll protection loans, etc? Or is this going to continue with this lower number of bankruptcies? And I’m worried that when the stimulus goes off and the fact that we haven’t had it, also even if we get an after the election or after January 20th when we’ll have a new president, perhaps, then the question is, is there going to be a second wave? And then that will slow down the recovery. So that’s what my biggest concern is now and the debt bubble along with it. At the same time, we’ll see, it could be some of my good friends who are macro forecasters are saying, “You know, the worst is over. It’s all now in recovery, and that’s why the stock market’s doing so well.

Meb: What’s been your most memorable investment on your own as you look back over the years? Could be good, bad, in between, anything seared in your brain?

Ed: Well, certainly the most profitable one is I usually lecture not to do this, but I did it and it worked out great, was investing in a small private startup in a high-frequency trading area back in the late 80s. A good friend of mine, an ex-academic, Dave Whitcomb, started this company called ATD. The whole idea was to be more efficient in your trading and by taking advantage of momentum, of positive and negative. Anyway, that turned out to be a super home run because it became such a fixture in the financial markets. Not everybody’s in love with high-frequency trading, but that from an investment standpoint company did very well for a long time. Other than that, I’ve really been very happy with the evolution of company financing for, let’s say, non-investment grade companies, not only in the U.S. I’m now in the middle of a evolutionary new market in Italy called mini-bonds which is like the high-yield bond market in the 80s. Now it’s in Italy. And these are small and medium-sized firms coming to market directly. But the thing that the investors need is more transparency of the risk and return trade-off. And so we’re working with that situation now, and hopefully, that market will develop. Other than that, I’m a decent stock picker. I’m a terrible stock seller. I just never know when to sell.

Meb: We talk a lot about that, but it’s never an easy answer. I mean, the answer for so many as almost like put it in the coffee can, the lockbox, leave it, don’t touch it. But then those winners often become big and then they become such a big part of the portfolio, the position sizing. All the emotions creep in and it makes it challenging and fun all wrapped together.

Ed: Or you get dumped in other things and you don’t follow what you originally were interested in.

Meb: Ed, people want to follow your writing, they want to kind of keep up to date with what you have going on. Do you got a homepage? What’s the best place for people to go?

Ed: I do have a website. We do have a new book that recently came out, so hopefully, people will look at that. It’s the fourth edition of our “Financial Distress and Bankruptcy and Restructuring” book. I’ve got two fantastic new co-authors, Edith Hotchkiss and Wei Wang. We keep trying.

Meb: Wonderful. We’ll post links in the show notes to all the papers, websites, books, all that good stuff. Ed, it has been an honor. Thanks so much for joining us today.

Ed: Thank you, Meb.

Meb: Podcast listeners, we’ll post show notes to today’s conversation at mebfaber.com/podcast. If you love the show, if you hate it, shoot us feedback@themebfabershow.com. We love to read the reviews. Please review us on iTunes and subscribe the show anywhere good podcasts are found. My current favorite is Breaker. Thanks for listening, friends, and good investing.