There are a lot of investment sayings that get repeated by individual & professional investors alike.

One I hear parroted over and over again is a variation of “high stock valuations are fine since interest rates are low”.

But did you ever stop and ask, “Is that true”?

This thread was inspired by a tweet poll I did a few years ago, in which I asked, would you still own stocks if they reached 10-year price to earnings (CAPE) ratio valuation multiples of 50-, or 100-times earnings.

And I was shocked, but most said they would still own stocks at 50, and many (a third!) said they would own them at essentially any price (100).

This had me scratching my head as it sounds totally insane.

Most investors use a value approach when it comes to buying assets like cars, houses, etc.

How long would you spend before buying that new 80-inch TV? (OK maybe less now with Wirecutter)

But time spent to think about investing your life savings?

Many are just willing to clickautoinvest into stocks at any valuation level.

Historically investing in stocks at sky-high multiples is a horrible, terrible, no good idea.

Again, most are willing to continue to hold stocks at a higher valuation than the internet bubble in 1999.

Many, a third, would still hold stocks at a higher valuation than ever recorded in any stock market in history, Japan in 1989.

And we all know how that didn’t work out. Thirty years of zero returns (though they’re looking spicy now!!)

The reasoning is usually: “high stock valuations are fine since interest rates are low”.

(To which I normally respond, well why are valuations so low in the rest of the world with lower, or negative rates vs. the US? We’ll come back to this later…)

Let me preface this thread by saying that many other researchers have already done a fine job of debunking this claim. Their work tends to lean academic, so I thought I’d try to frame it in a slightly different way.

Check out Asness, Arnott, Inker, Bernstein, Bogle, Hussman, Shiller and many more – I’ll try and link to some resources at the end.

You can also download and play around with Shiller’s excellent Excel databases – would love to see people expand upon (or critique) anything here. List of resources

My top 5 Global Stock Valuation resources (including downloadable CAPE ratios):

We’re going to use the 10-year PE (CAPE) ratio. This often causes peoples brains to short circuit.

You could replicate this entire thread with dividend yield in lieu of CAPE ratio and it will give you the same results. Seriously, try it.

Q1: “When stock valuations were at their highest, were bond yields low?”

Stock valuations have ranged from a low of 5 (1920) to a high of 45 (1999) with the average around 16. We’re at 34 now, which has only been exceed once in history, the internet bubble.

The top 10% of stock valuations is basically any CAPE ratio over 25. The average bond yield during this period is 5.1%. So, that feels high relative to now, but about average over time.

What about over 30 CAPE ratio? Even higher bond yields at 5.5% So, high stock market valuations have historically occurred in tandem with average or higher than average bond yields.

Ok, let’s ask it a different way and flip the criteria.

Q2: “When bond yields are low, are stock valuations higher?”

If you examine the bottom quintile of bond yields, the average CAPE ratio valuation is actually below average, or around 13. (This applies to short and longer term 10-year yields alike.)

Weird. Backwards from what most people say.

Hmmm, ok. Maybe we’re missing something…as we know it’s hard to compare yields across time since inflation at 2% isn’t the same as inflation at 10%.

Q3: “What is the relationship between stock valuations and inflation?”

Inflation and bond yields tend to be tied at the hip. Valuations do roll over as inflation picks up > 4%, where investors are willing to only pay a CAPE ratio valuation of about 10. Below 4%? Double that to around 20.

So, investors seem to like the 1-4% inflation range as a warm and cozy zone and will pay more for that certainty.

Ok, some would argue that “no, it’s not the level of interest rates, it’s the direction” which is of course true, but this requires you to accurately forecast future interest rates, which to my knowledge, no one can.

Also, the change in interest rates doesn’t affect the valuation that much, in both bottom and top quintiles of historical bond yield moves it results in a few total CAPE ratio points over 10 years.

Again, IF you got the interest rate prediction correct because the opposite is also true. There seems to be a universal assumption that bond yields in the US can only go higher and not negative, which is odd given most of the rest of the world is already there…

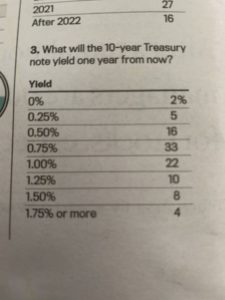

Barron’s didn’t even include negative rates as an option in their recent poll

Ummm, seems like one choice is missing?!

Ok, so all we know so far is historically investors have rewarded low nominal and real bond yields with lower valuations on stocks (largely due to lower trailing earnings growth).

Investors are also willing to pay bit more for stocks when inflation is tame. But none of this is what people are really asking.

When they say that

“high stock valuations are fine since interest rates are low”,

what they really mean is

“high stock valuations are fine since interest rates are low, therefore future stock returns will be ok.”

Honestly no one really cares about if current multiples are “justified”, what they really care about is if those valuation multiples and low bond yields produce higher or lower stock returns in the future.

So, let’s query differently, Q4: “when bond yields are low, are future stock returns higher?”

And it turns out the answer is yes…In fact, the lowest quintile of bond yields results in high real stock returns of about 10% over the next 10 years, above the 6.5% average.

See Meb, you are an idiot! Stick this discounted cash flow where the sun don’t shine.

Well, hold on a second…we all know nominal doesn’t really mean anything, so let’s examine real rates…

In fact, the lowest quintile of real bond yields results in high real stock returns of about 11%, also above the 6.5% average. Even better.

Ditto for future stock vs. bond returns though this is dominated by the stock side. (Btw, everyone in the media has misinterpreted Shiller’s new article and Excel, I suggest you take it for a spin and come to your own conclusions…) Ha, I know you were an idiot Meb!

But that’s just scratching the surface. Tren Griffin is going to murder me for the rest of this thread but I think he may agree that using one variable is too simplistic perhaps.

As mentioned previously there are numerous factors at play and isolating any one doesn’t reveal the full picture.

So, when sorting by bond yields and future stock returns, where are valuations?

The lowest quintile of bond yields, that resulted in high future real stock returns, had on average a starting valuation of 13 and a dividend yield of 5.4%. More importantly, they ended the decade on average with a CAPE ratio of 18. (aka valuations went UP)

The lowest quintile of real bond yields, that resulted in higher future stock returns, had a starting valuation of 11 and a dividend yield of 5.7%. More importantly, they ended the decade on average with a CAPE ratio of 18. (aka valuations went UP)

Valuation multiple expansion over 10 years can easily have a 5-7%+ tailwind per year from these low starting valuations.

So, was it the low starting bond yields, or rather that they occurred along with low valuations and high dividends that drove the returns?

Strip out the valuation move and low nominal or real bond yields regimes are nothing special.

Historically you had a higher future real earnings growth from low yields, a percentage point or two higher, largely due to lower trailing real earnings growth. Also, trailing stock returns were lower than average.

Notice we have low bond yields today, but valuations are TRIPLE the average starting valuation in our example, and dividends less than half historical averages.

Let’s walk through one last exercise for fun.

Let’s reverse back the starting conditions for the best (and worst) performing quintile of stock returns in history.

What conditions are present when we observed the best stock returns ever? Almost 20% REAL returns for a decade …Ah to be alive in 1920*…

Perhaps we’ll have the roaring 2020s, I sure hope so. I miss live music, Irish pubs with Guinness on tap, and on and on…

*You would have had to be solid on your timing, 1930 gave you no real returns for a decade…. amazing how the best of times often leads to the worst, and vice versa…

On average the best returns in the top quintile gives you 14% real returns for a decade.

On average the worst returns in the bottom quintile give you -1% real returns for a decade.

Pretty big difference in outcome for the buy and holders.

The conditions at the start of these big return periods, on average have been high dividends, low valuations, average bond yields, lower trailing real stock returns, lower trailing real earnings growth, and higher trailing inflation.

The conditions at the start of these bad return periods, on average has been lower dividends, higher valuations, average bond yields, higher trailing stock returns, higher trailing real earnings growth, and lower trailing inflation.

Not sure if this will be visible, otherwise will add link later…

Most importantly, if you strip out the 7% per year tail/headwind of valuation expansion/contraction, the average real returns of the best/worst bucket are in line with average returns. Valuation seems to have a pretty massive influence on the best and worst decades.

Let me restate that: most of the excess returns from the best performing stock periods have come from valuations going from really low back to average or above. (and vice versa).

Bogle himself published a similar article about this….in the 1990s and later updated as “Occam’s Razor Redux”. Future stock returns could be distilled to just:

Starting dividend yield + earnings growth + change in valuation. (You can also decompose earnings growth into real earnings growth + inflation. Buybacks increase the dividend growth but inflation has been lower than historical so they sort of wash out vs. history right now.)

You know two of the starting variables (dividend yield and starting valuation), you don’t know the other three (future inflation, future real earnings growth, and ending valuation.).

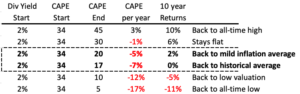

But historically you can come up with a matrix to give you a good idea of where we might be going. And in most cases, it isn’t pretty. I think the base case for US stocks is about 0-2% real returns for a decade.

Recall that most investors expect 10% returns on their portfolio. Some, like recent surveys, expect 15%.

For 10% you need valuation multiples to go up to the 1999 peak, for 15% you need them to hit Japan levels…is that likely?

These scenarios assume historical growth rates, which, depending on who you ask could be massively over or understated. As we mentioned prior, low bond yield environments tend to be associated with lower past real earnings growth and higher future earnings growth.

Now, as any experienced (cough, older) market investor will tell you (or show you with scars), markets have a way of making you eat humble pie. So, it’s always interesting to think of how you could be wrong.

One positive case I can fathom is an actual explosion in innovation and entrepreneurship. My chat with Vanguards Joe Davis would point in that direction.

Those that read my piece “The Get Rich Portfolio” know that I invest a significant amount of my net worth into startups (over 200 and counting) for this reason.

And also, the QSBS rules which could be the most significant part of this thread that no one understands. Google it, taxes usually have more of an impact than any of this stuff.

Maybe we’ll all live to 200 and be teleporting to Mars. But you have to recall that our historical results included plenty of innovation too like railroads, cars, telephones, internet, antibiotics, and Taylor Swift.

So, this low bond yield environment could add one or two percentage points to real earnings growth. That would take real returns from 0-2% to 1-4%. Still not great. (My friend John Hussman would interject here with some discussion on profit margins I imagine…)

You don’t have to invest in the market cap weighted passive index. There are pockets within the US stock market that offer opportunity, such as low valuation, high cash flow companies distributing cash to shareholders via dividends and net buybacks (aka shareholder yield).

If an innovation renaissance were the case, I would much rather own stocks in foreign stock markets, where the starting conditions are flipped with low valuations and higher dividend yields.

Foreign developed has an average country valuation of 22, with emerging markets at 15. (and the cheapest bucket is at 11!) Dividend yields are much higher too.

But it’s also helpful to fathom the bear case too. What if US stocks don’t just go back to average valuations, but sail through them? What if inflation ramps and growth stalls out?

As 2020 has reminded us, anything can happen in markets. We talked about this in March when we outlined the bull and bear case for stocks. Believe me, judging by my inbox, no one thought we’d be hitting all-time highs by year end…

Ok, time to wind down. So many times on social or TV you hear people rant and rave and then often there is no practical conclusion.

There’s plenty of diagnosis but no prescription. So, after all this theoretical discussion here’s both my diagnosis and prescription…

Diagnosis:

The good times often follow the bad times in markets and economies. And vice versa.

Super technical I know, but true.

Starting conditions for US stocks are not great. Low dividend yields with high valuations mean future stock returns could be lower. Bond yields don’t offer an attractive alternative.

You could reasonably forecast no real return on either investment for the coming decade.

Real earnings growth may be higher than average.

Starting conditions for foreign stocks are much better. Higher dividend yields with lower valuations mean future stock returns could be much higher. Value tilts within these markets are even more extreme in the positive.

Realize markets will continually surprise me and all of the above could turn out to be wrong for long and painful periods of time.

Prescription:

If you have a basic buy and hold portfolio continue to rebalance, or more aggressively what Arnott and Howard Marks mentioned in our podcasts, an opportunity for an “over rebalance” or “tilt”.

Take your medicine and expect lower stock and bonds returns in the US. Be prepared for the possibility of a normal 50% decline in US stocks. At least consider

Consider diversifying to the global market average stock allocation, which is roughly half US and half foreign stocks (most Americans hold 80% in US stocks).

If you’re bolder, consider breaking the market cap link to a larger allocation in line with global GDP, where the US is only 25%. In particular value stocks in places like emerging markets (where most Americans have a 3% allocation) look like great.

I’ve mentioned on twitter I invest my sons entire 529 and my entire 401k in foreign and emerging stocks. And given the reactions on social it makes me think it’s a brilliant decision…

More on the global value opportunity here.

Consider alternative strategies like trend following, tail risk hedging, real assets like farmland, or market neutral & arbitrage style investments.

Also consider ignoring all of the above, buying the global market portfolio with low cost ETFs and getting on with your life…after all, I love saying “most investors try to be Nostradamus when they should aspire to be Rip Van Winkle”

Write down your plan and share it with someone to keep you honest…

Here’s a fun old post to get you started…

That’s all for now folks!…until then, happy start to 2021 everyone!